Toys and simpler times

“One day, you and I will be as far apart as this kite is now from the natai,” he said and giggled. “You will be a gentleman working in an air-conditioned office. I will be a labourer in some distant land.”

I did not pay heed to his words. I was too engrossed in the all-green world, too much in bliss as I was on a Baishakhi holiday at my dadu-bari far away from school, and too tired from roaming endlessly in the village fair — from where we bought green plastic “sunglasses” which, when worn, made everything look green.

And Johnny, my childhood friend, often used to say things like that anyway. Even though we were of the same age, his soul was that of a wise old man.

For him, coloured sunglasses, kites, and the myriad toys that we saw in that mela many Baishakhs ago were his constant companions. For me, those were objects of marvel for the few days every year that I spent in the village. Not that they never appeared in the city, but I was more in touch with my fellow soldiers of the G I Joe team and Nintendo’s Mario.

But now, looking back, I miss those local toys and playthings.

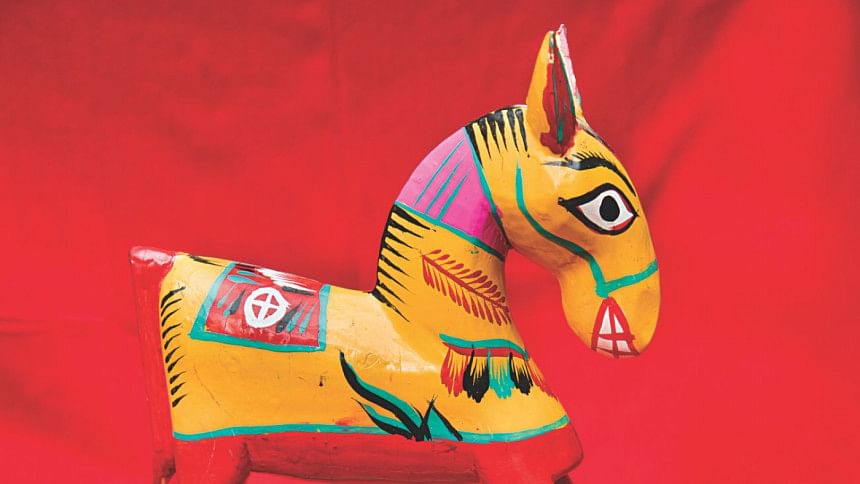

Deshi toys do not just evoke nostalgia; they reflect local craftsmanship and our culture and heritage. And the array of toys indeed has a very rich variety, from the perfect latim to crude dolls.

Just take dolls as an example, which have been here for centuries. In his book Dui Banglar Putul, Fokhre Alam writes that dolls of antiquity were dug out from the archaeological excavations at Savar, Mainamati and other places.

The book talks of several kinds of dolls.

There is of course our all-too-familiar tepa putul — made with clay, shaped by hands, hardened in kilns, and nowadays, coloured as well.

The book also tells us of the “ghar nara buro putul,” characterised by a figure whose head shakes like that of an elderly person, made possible with a spring in the neck.

Simple mechanisms used to make such toys more fun.

Mechanisms like that of the popular talpatar shepai. The figure is made with palm leaves and thread. Eyes, nose, etc. are drawn. It comes to life with a simple mechanism of thread and a stick attached to its body; the figure makes simple movements as you move the stick.

The very fact that it is crafted with palm leaves hints to the variety of materials that are being used for making toys.

Clay is common. Some other materials include paper, wood, bamboo, jute, cloth, etc.

Not all dolls came home from the market or the hawker. A few were made at home by children.

“We used to wrap cotton in a small piece of rag, eventually giving it a human shape,” Rubana Aziz, now 60, recollects memories of her childhood, which she spent in the city of Cumilla. “With small sticks, wires, and other insignificant objects, we would make the dolls, and then drape a small make-believe sari over it. That’s what you would nowadays stylishly call DIY crafts!”

It was a world of imagination for her, be it marrying off the dolls, or cooking with clay-made miniature pots and pans.

On the hand, latim seemed to a favourite of a lot of children, including my friend, Johnny.

Now, he was a master of the spinning top! No matter how he threw it, the latim would somehow land flawlessly and balance itself perfectly to spin for a long time.

We would also play with marbles. Small holes were dug on the ground. The attempt was to roll off the marble balls from various distances into the holes.

Meanwhile, my most cherished plaything was the gulti (i.e. slingshot). I loved firing pebbles or stones high up in the sky, or target practice with scarecrows, or wage a war against a fleet of paper boats by attacking them from faraway with the simple Y-shaped weapon.

Johnny and I would be lost in our make-believe world.

But as we grew older — from around the age of 12 — harsh realities started to seep into that world for him. He was pulled out of school and put into petty and odd jobs to help his family.

There was a gap emerging between us. We still played; but Johnny seemed less into it.

Anyway, another local plaything which was rather ubiquitous was the pull-toy. It came in various colours and folk designs, and often had a drum fitted to it.

“We used to call it temtemi or tom-tom gari. When you dragged the cart with a string, it made a distinctive noise,” Hosne Ara, a homemaker now in her late forties, said. “It was more of a rattle.”

Quite a few noisy toys, such as the classic dugdugi, indeed held a lot of fascination among children.

Perhaps because those were simpler times, with lesser entertainment options? There was no Netflix or Instagram, and even the camera was still beyond the reach of many.

And hence, Israt Ara, now a senior manager at a local company approaching her retirement, still vividly remembers the excitement surrounding a small plastic “camera” during her childhood in the 1960s in Dhaka.

“The camera came with some sort of a film roll. When you inserted it and peeked into the device, you would see images,” she explained.

From the plastic camera to the universal slingshot, and from the various kinds of dolls to the different types of the rattle, these simple and rustic playthings gave many generations before us a magical childhood.

Some of these toys can still be seen, albeit the fact that they are now being overshadowed by newer and fancier ones.

The locally made toys — some more deshi than others — reflect the simplicity of a time long gone.

Times have changed. So have we.

Gone are my childhood days. The sky has not turned green for decades. Neither do I launch stone missiles at paper boats with a slingshot. Nor does Johnny spin any latim.

As for him, life was less kind. He went overseas to become a construction worker, sweating out endless hours in pursuit of supporting his family as the sole breadwinner. But he is earning well.

We have not spoken to each other in years — we moved onto our separate ways and became busy in our struggles and made new friends.

But when I see a latim spinning, or when I hear the deafening noise of a dugdugi, it reminds me of my friend and our make-believe worlds — my lost childhood, local toys, and simpler times.

Photo: Sazzad Ibne Sayed and Intisab Shahriyar

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments