Quamrul’s Bengal

We vow to serve the cause of the land of Bengal;

We’ll bring the vivacity of youth back to life;

We’ll build our bodies, open our minds;

We’ll stick to our pledges till we die.

— Oath of the Bratachari

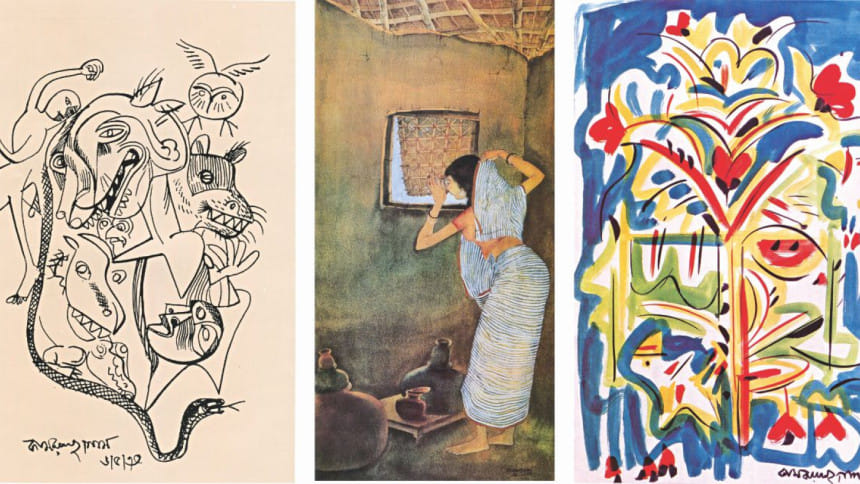

February 2, 1988. Presiding an evening session of the Second National Poetry Festival at the University of Dhaka, famed artist Quamrul Hassan doodled what would become one of the most important works of his career, and our art history.

“Desh aaj bishwa behayar khopporey” [The country today is in the hands of a global scoundrel] eventually became an inspiration for the mass movement that saw the downfall of autocracy in 1990. Never shy to align himself with truth and justice, Quamrul sketched the image of a snake entangled around a jackal, and a human face that seems more evil than Satan himself. It was simply a demonstration of the power of creativity; it confirmed the might of art.

HIS FORMATIVE YEARS

Quamrul Hassan’s illustrious career spanned more than five decades, and he remained devoted in the revival of folk culture and traditions in the forefront of contemporary art movements, without sacrificing his academic training on artistic practices. In all possibility, Quamrul Hassan still remains the most accomplished artist who has skilfully infused folk elements of Bengal with modern art— indeed, he was a ‘potua,’ but one who addressed a global, often urban audience.

His artworks reflected the image of his inner being, and he felt a compulsion to present beauty, as well as the evil that surrounds it. His paintings are never devoid of imagery — women, and the lives of women in various forms; the romance of rural landscape; but he also presents the wicked and sinful, and again through pastoral parables — venomous snakes, cunning jackals, ominous owls, monstrous crocodiles, cold lizards, and ravenous vultures.

Despite coming from a conservative Muslim family of what was then unified Bengal under British rule, Hassan chose to be an artist, and along the way, became involved in socio-political activism in all fronts. His political ideologies were influenced by several leading communist leaders, while his thirst for art was being nurtured at the Government Institute of Arts. But his everlasting love and passion for everything Bengal can be attributed to his close association with the Bratachari Movement.

Inspired by the teachings of Gurusaday Dutt, Hassan developed a sense of universality and actively nurtured the positive aspects of the mind and the soul. The ideals of the Bratachari Movement encouraged its disciples to go back to the traditions, the folk cultures, folk dance forms, and musical renditions. And that is exactly what Quamrul Hassan accomplished as an artist.

His experiences at the formative years gave Hassan the foresight to transcend a slavery of the mind, bound by caste, religion, gender, and age. Indeed, it was through the Bratachari Movement that he was introduced to ‘pata painters’ of Bengal, and once again, his experience would be something he carried for the rest of his life.

THE POTUA

After the partition of 1947, Quamrul, along with his family, moved to Dhaka, and together with artists like Zainul Abedin, played a vital role in founding a school of arts in hitherto East Pakistan. In the same year, he took up teaching at the Government Institute of Arts, the very institution he helped establish.

Hassan’s initial attempts to create his own style was inspired by the philosophy of the Bratacharis, and he had learned the significance of the age-old art form of pata chitra from Guru Saday Dutta himself. Without compromising on the tradition of pata, Hassan’s paintings created a three-dimensional image without deviating from using the monochrome, non-tonal hues common in traditional pata chitra.

Hassan juxtaposed myriad colours, giving a sense of depth or distance between the settings within the painting itself. Critics acknowledge that Quamrul Hassan succeeded in giving a three dimensional perspective to traditional patas that were ubiquitously flat, and most importantly, two dimensional.

One of the legendary artists to have made use of this simple technique of creating 3D effects using non-tonal variations is the iconic French artist, Henri Matisse. In fact, throughout his entire career, Hassan was heavily influenced by Matisse, and also Pablo Picasso.

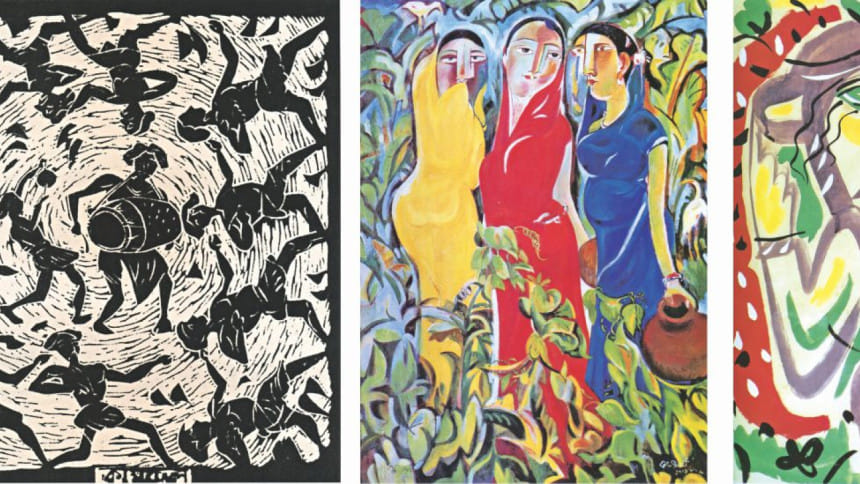

In creating the much acknowledged effect, Quamrul made profound use of lines, and techniques taken from the cubists. Even in his pastoral depictions, often, rather than going for plain realism, he deconstructed figures and landscapes, and then put his creative zeal in the reconstruction, at times making use of geometric forms.

THE SOUL OF AN ARTIST

Although quintessentially Bengal, neither did Hassan rely on motifs, nor do his patas explore religious depictions. In every painting of Hassan, one can easily relate to his sense of belonging to what he explored, and the obligation and nationalistic fervour that he upheld. It would not be wrong to say that in each of his works, one finds an enthusiasm to explore the ethos and the essence of the land he was born in; the land he traversed.

Art is often a spontaneous outcry; at times it is a deliberate attempt to accomplish and present a certain theme and set a trend. Throughout his career, Hassan seems like a believer of the second.

He experienced Bengal in its myriad forms, and his art reflects that very experience. When one attempts to explore the entire gamut of his works, it becomes clear that all his creations are mere reflections of his mind and soul, and the journey of his life. Thus, we see him engage in creating art and crafts in post-71 Bangladesh, borrowing even from his pre-partition experience.

Women are his most recurring theme. One finds the women in Hassan’s works in groups, at times engaged in a chit-chat; on the fields in times of harvest. As a painter, Hassan was an observer. Although modern by all means, he utilises a fusion, but never allows his urban existence touch the rustic landscape.

Although the formative years of his life was spent in West Bengal, it was only after his migration to East Pakistan that he was fully exposed to the beauty of rural Bangla. In the course of his career, the pastoral setting of Bengal was ever changing, yet Quamrul remained loyal to the images captured in his memory.

Hassan was also one who’s creations were built on his personal journey, and the varied depiction of women throughout his entire career is a testament to that. The phases encompass the experiences of a child and dreams of youth; the bliss of marriage; and the sour notes of nuptial bonding. Yet, one must realise in none of this periods did his imagery take a scornful tone.

The first stage marks the memories of his late mother in utter simplicity. This phase also sees him draw women in groups, mostly in three. Perhaps — a mother, a wife, and a daughter. One can never say.

Hassan painted women, but he also painted experiences. The bare-breasted images of women in his later paintings may have been a symbol of vitality of life. When he chooses to draw his muse, often a woman taking a bath, it is more of a reminiscent of the glory days of Bengal, the lyrical picturesque setting that has been lost with time.

What some critics finds most exhilarating is his repeated use of poster colours for his imageries. Loud in their tones, he completely abandons the pata style and creates a new form of painting, ubiquitously Bengali, but quintessentially global.

A LINGERING CONSCIENCE

The evil he encountered in society troubled Quamrul Hassan; it touched his inner conscience and his response was multi-dimensional. His presence in the socio-political scenery was not only visible, he was one of the trend breakers.

Experimenting on art in East Pakistan was not an easy task, as the people of the entire Pakistan were burdened with a religious overtone, and artists could not help but respond. Ever since the formation of Government Institute of Fine Arts at Dhaka, Quamrul took it upon himself to bring acknowledgement and recognition to what was then a highly neglected arena, commercial art. He was the mastermind of several art events, and through them, art was presented to the people in a new form.

In 1960, Hassan gave up his position at the Art Institute and helped establish the East Pakistan Small and Cottage Industries Corporation, and between 1960 to 1974, Quamrul played one of the most pivotal roles an artist can play in shaping the minds of a nation. He was active in the struggle against the autocratic regime of Ayub Khan, and became engrossed with the freedom floating in the air after 1 March, 1971.

On 23 March, he put up at least ten propaganda posters, portraying a monstrous face of Yahya Khan, which inspired the freedom fighters. This would later form the basis of the iconic demonic depiction of Yahya Khan, with the simple, powerful slogan — ‘Annihilate these demons’.

Following the events of 25 March, Quamrul Hassan left for India, and joined the struggle for liberation by serving as the Director of the Art Division of the Information and Radio Department of the Bangladesh Government in exile.

Following Victory on 16 December, Quamrul returned to Bangladesh, and once again, played a pivotal role in establishing art in a new country, just as he did post partition.

Between 1971 and 1974, he masterfully executed the designs of the state monogram of Bangladesh, Freedom Fighters Welfare Trust, Bangladesh Parjatan Corporation, Bangladesh Bank, and Biman Bangladesh Airlines.

He played an active role in creating a positive image of an emerging nation by overseeing the designs of stamps and currency — tiny ambassadors that often contribute more to creation of a national image than any other means.

That is not where he stopped. In 1974, in a series of prints done in linocut and woodcut, he presented his anguish for what he felt was the degeneration of the zeal of freedom; he vividly presented the erosion of spirit, the corruption of morals and ethics over personal gains.

Perhaps, for an artist who is so moved by the beauty around him, and disturbed by the injustice engulfing us since, the artist Quamrul Hassan was always the one to protest through the medium he knew best — art! He took the oath of a Bratachari in his youth, and true to his conviction, he did stick to the pledge till his last breath.

Picture scanned from Quamrul Hassan, Part of Art of Bangladesh Series-3, Published by Department of Fine Arts, Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments