Two New Years in One Calendar

People have celebrated New Year either at the beginning of their solar or lunar calendar; or when nature sent fresh air. That fresh air is the beginning of spring or autumn.

Ancient Persians (Iran) celebrated New Year with the beginning of spring. They called it Nowruz (New Day). As the winter ends the snow starts to melt. Flowers start to bloom. The rivers start to flow. Nature wakes up. People are happy to celebrate. Before the Roman colonisation of Europe that saw January becoming the first month of the Gregorian solar calendar, the ancient Europeans used to celebrate their New Year on the first day of spring (the spring equinox). That festival still survives today as Easter.

Since antiquity, Bengal welcomed a New Year with the fresh air of late autumn (Hemanta) when the majority of the people, the farmers, had food to celebrate from the Aman harvest. The festival was aptly named 'Nobanno' (new food). When the Bangla calendar (Panjika) started, all the months of the year were named after a star or a constellation. There was once exception. That was Agrahayan. Literally, Agrahayan means the leader. Pahela Agrahayan celebrated Nobanno and the New Year. For centuries this was the situation. Emperor Abul Fath Jalal Uddin Muhammad Akbar, or Akbar the Great, abandoned the lunar calendar for convenience of tax collection to run the Mughal Empire. He started the New Year on the first day of Baishakh. Pahela Agrahayan lost its prominence as the New Year forever, but the celebrations of Nobanno survived.

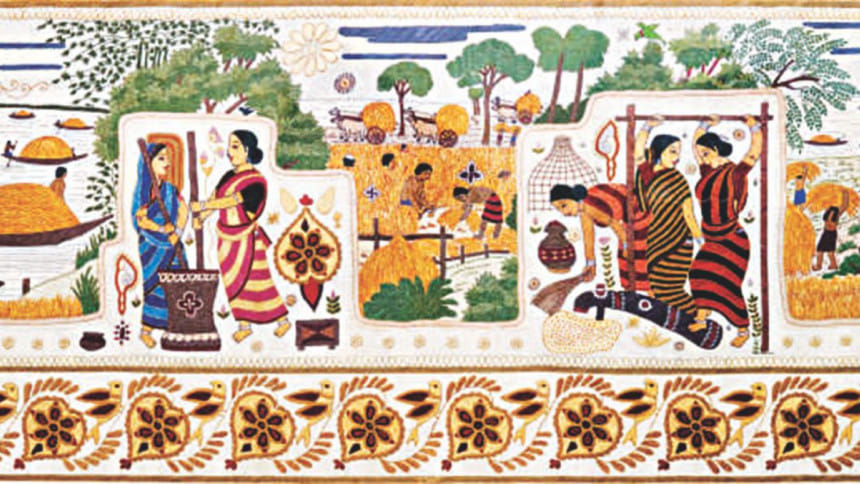

The Aman harvest of Kartik would determine a farmer's fate. A good harvest meant the family was safe for one more year. The family and the village would celebrate Nobanno with pitha, khoi, muri, mowa, and firni. Hemanta would turn the green fields and the banks of the rivers white with Kash flowers. Singers would sing. Dancers would dance. Kites would decorate the autumn skies. Rural Bengal would overspill in festivities and the squeaking noise of the Nagordola. Women would immortalise Nobanno with tapestries (Nakshi KaNtha) like the ancient Egyptians did with their Hieroglyphs or the cavemen of Altamira in Spain did thousands of years earlier.

The fate of the farmer depended on the weather. If the weather wasn't kind, there would be no crops to harvest. The rural economy of Bengal didn't have safety nets like today. The farmer would end up entering an inescapable bond with the moneylender (Mahajan).

The rural landscape of Bangladesh has changed. Bangladesh is now in the top tier of countries with the highest economic growth rates. Growth rates, however, haven't changed the urge to find an excuse to celebrate a festival. As the old saying goes, in Bengal there's a parban (festival) for every occasion.

Not too many calendars can boast two New Years. The Bangla calendar has Pahela Baishakh and Pahela Agrahayan. Off to Charukala. The Feedback song, Melai Jaire is not only for Pahela Baishakh but all the festivals in Bangladesh.

Asrar Chowdhury teaches economic theory and game theory in the classroom. Outside he listens to music and BBC Radio; follows Test Cricket; and plays the flute. He can be reached at: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments