At the intersection of conflict, climate change and energy access

With the advent of the 21st century, there has been a steady rise in energy access all around the globe. For the first time ever, the total number of people without access to electricity fell below 1 billion in 2017 according to the International Energy Agency. Despite the increase in the pace of electrification, 13 percent of the global population, mostly concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, still lack critical access to electricity—a factor linked closely with productivity, health and safety, gender equality and education. Without much greater ambition and more intensified efforts, the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 that has an objective of "ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all" will be impossible to attain by 2030.

At the same time, as the global community faces the persistent and pervasive challenge of energy poverty, it also needs to address the intensifying human-driven climate disruption and the widespread displacement of people as a result of war, persecution and natural disaster. These critically important crises—energy poverty, climate disruption and displacement—are inexorably linked through the strong overlap in the populations affected by all three predicaments.

There is an unprecedented 68.5 million people forcibly displaced across the world. Many of them end in relief camps, where approximately 90 percent do not have energy access as stated by the Center for Resource Solutions. In addition to refugees and internally displaced persons, majority of the people lacking the most basic of electricity services also count amongst the population most vulnerable to the disastrous consequences of climate change. Mass migration ensuing from the dramatic shifts in our environment has the potential of fuelling political unrests and exacerbating conflict. The communities at risk often lack both the political and economic resources that are essential in maintaining stability through strengthening climate resilience and adaptive capacity. As a consequence, many countries with significant energy poverty will bear the worst effects of global warming despite having contributed very little to the historical build-up of greenhouse gas emissions.

Taking constructive steps towards climate change mitigation and achieving universal energy access supposedly seem to be in conflict. The reasoning behind this sceptical notion is the assumption that more people getting access to electricity will require further investment in carbon-intensive power systems and greater exploitation of fossil fuels which largely contribute to the vast majority of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. However, with rapid advancement in alternative energy technologies primarily in areas of efficiency and cost-reduction, it is no longer required to address one crisis at the cost of the other. In the current scenario, communities enduring extreme cases of energy poverty often depend on biomass burning to meet basic energy needs. Replacing biomass with clean sources of energy will significantly bring down deforestation, a step that is vital for climate mitigation and adaptation. Renewables like solar photovoltaics (PV) and wind turbines are less expensive than newly installed fossil-based power plants in many regions of the world and in some, it is even less expensive than using existing, traditional power plants.

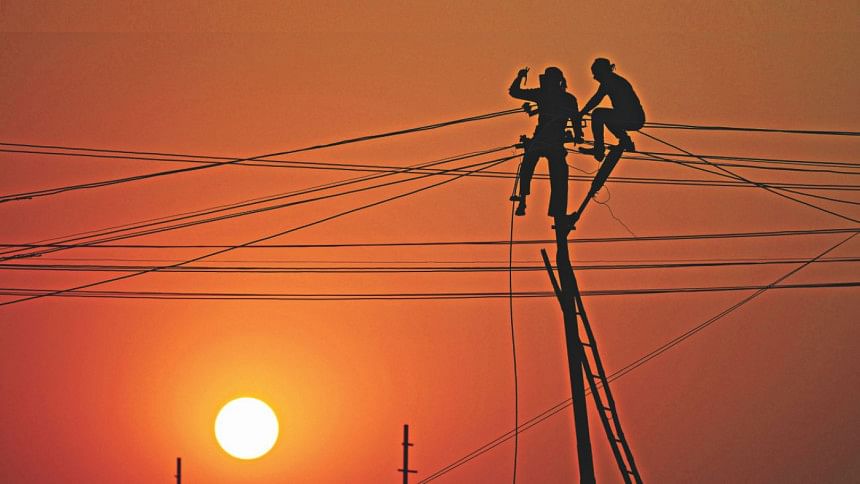

Communities in remote, rural areas or refugee camps located near borders and inhospitable regions of the world are usually situated far away from traditional transmission lines. Installation of capital-intense grid network is economically unviable as reaching an affordable scale in these places is nearly impossible. In recent decades, decentralised energy solution is becoming an increasingly important factor for expediting electricity access. Deployment of distributed infrastructures is powering a disruptive transformation in the energy sector like never seen before. Through the latest policy brief for SDG 7, the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs emphasised that for over 70 percent of those without access in rural areas, decentralised systems based on renewable energy will be the most cost-effective solution.

The new paradigm demands that decision makers think beyond the "grid versus off-grid" dichotomy and recognise the extensive value of autonomous mini-grids and distributed energy services that utilise local resources and effectively serve specific, regional needs. Reducing dependence on centralised generation further democratises the electricity distribution allowing for local ownership of energy services and increased support for alternative energy. Widespread adaptation of distributed systems based on renewables will put a check on the global demand for oil, ease the power struggle over resource-rich areas and cut down energy dominance in political negotiations. Such a transition will help nation states in reducing vulnerability to conflict, and strengthening socio-political stability.

Given the far-reaching benefits and rising practical feasibility of renewables, it is likely that the global community is heading for a future that embraces clean power sources. However, the ultimate question is, will the transition be fast enough to limit global warming to a safe level? The special report on Global Warming of 1.5 degree Celsius published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns that increase in temperature beyond 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels will lead to severe environmental catastrophes and the international community has 12 years to limit that.

As the 25th session of the Conference of Parties (COP25) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change draws near, it is critical that governments, negotiators, and other stakeholders not only consider a rapid shift towards a clean energy future, but also a transition that is just and inclusive of unserved and underserved communities. While international support is certainly essential in achieving SDG 7, real and lasting progress will also require participation at the national as well as local and regional levels. With the emergence of decentralisation in electrification, the energy sector can greatly benefit from polycentrism—the contribution of multiple stakeholders from numerous spheres.

The present day is a unique moment in the history of energy access expansion, as distributed networks can viably reach the furthest corners of the globe. It's critical to make the best use of this opportunity and drive action towards an energy system that will sustain the earth for future generations, while also stepping up electrification and promoting regional stability.

Tarannum Sahar is studying Economics and Mechanical Engineering with a focus on Energy Transition and Technology Development at Cornell University, USA.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments