Children with Cancer: In silence, they perish

Mohammad Kabir Hossain, 43, had dreamt of building a house for his family using the money he saved from an overseas job. That dream, however, took a backseat when his third child was diagnosed with cancer. Kabir used up all his savings, sold whatever land he had, along with his grocery store, for his child’s treatment.

At the current rate, the treatment of his seven-year-old -- Nurul Islam Nayan -- should continue for at least another year and a half. He said he had already spent Tk 13-14 lakh and is now bearing a monthly expenditure of Tk 20,000 on therapies and medicines.

Nayan has leukemia, a form of cancer affecting the production of blood cells in the body. The disease is one of the most common childhood cancers affecting 18 percent of cancer patients below 14 years in the country, according to a 2016 research report published in BMC Cancer, an international peer-reviewed journal.

Worryingly, many people tend to put off treatment for such diseases due to the high costs involved.

About 35 percent parents stop continuing treatment half way through, while 12 percent of them refuse to receive treatment having been told about the costs.

Without treatment, and no oversight, many children die a silent death.

While infant mortality due to infectious diseases has declined over the last three decades by around 71 percent, more children are likely to be diagnosed with non-communicable diseases, including cancer, as they reach the age where it is likely to happen.

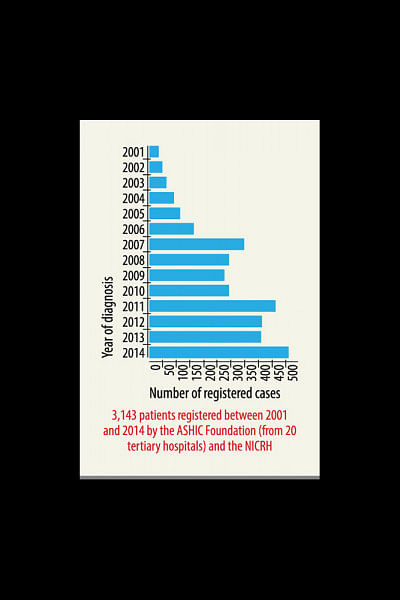

The study found a sharp increase in the incidences of childhood cancer from 2001 to 2014 with children below 15 years. The latest figure, of 2014, was still a lot less than the expected figure. When compared to childhood cancer incidences in other lower- and middle-income nations, including India, researchers expect Bangladesh to have between 5,500 and 6,700 new cases every year.

https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12885-016-2161-0

The report concludes that childhood cancer is expected to increase in developing countries by 30 percent by next year, influenced by declining infant mortality rate and population growth. Bangladesh, however, does not have the infrastructure to cope with such a change.

The burden of childhood cancer here remains unknown because of a lack of awareness among clinicians and the population, inadequate healthcare facilities and the non-existence of cancer registries, as suggested by the 2016 report.

Meanwhile, many parents, like Kabir, go broke while trying to mobilise the resources available to save their children.

Others seek alternatives like herbal treatment and homeopathy when they cannot afford or get access to facilities in the handful of public hospitals offering specialised care, said Prof Zohora Jameela Khan, of the paediatric hematology and oncology department in Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH).

EXPENSIVE TREATMENT

Estimating the cost, Zohora said it was Tk 5-6 lakh at the lowest for a patient beginning treatment at three years. “If the patient suffers infection frequently, the cost goes up.”

No less alarming is that five to seven patients are refused treatment every day for the lack of logistics at the 17-bed paediatric cancer unit of the DMCH.

The situation is similar or worse at Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU). The autonomous institute sees 15 to 20 patients compete for one seat, with the capacity to accommodate no more than 35 inpatients at a time.

The treatment cost at the BSMMU is much more than that in the DMCH, since patients don’t get anything for free except food, bed and doctors’ visits, said Momena Begum, of the paediatric oncology department at the BSMMU.

Overall, the country has only eight public hospitals with the required set-up -- five of them are in Dhaka, including the National Institute of Cancer Research and Hospital, the lone public hospital specialised for cancer patients.

POOR INFRASTRUCTURE LEADS TO POOR RESULTS

Access to affordable cancer care, however, can make a whole lot of difference, Zohora said, adding, if the diagnosis is done early and complete treatment given then “childhood cancer is curable in 80 percent of the cases”.

At the DMCH, 53 percent of those who undergo treatment get cured while 50-60 percent patients at the BSMMU get back a near-normal life following treatment. The figures exclude those who don’t continue treatment or reject it.

The existing over-crowded infrastructure also affects the outcome of medical procedures.

Medical experts say cancer patients require complete isolation for strict control of infection. But the hospitals have to accommodate more patients than what they can, increasing the risk of infection, which in turn hinders the progress in treatment and leads to additional spending on tackling infection.

And tackling infection is more expensive than routine cancer treatment.

Things would change with financial support from the government and infrastructural development, said Momena, of BSMMU.

If more facilities are set up, more doctors will be encouraged to take up specialised courses in paediatric oncology, Zohora said, referring to the fact that the country has only about 23 paediatric oncologists.

Meanwhile, Nayan’s father Kabir is weighed down by debts.

Every time he comes to Dhaka from Mehendiganj of Barishal for follow-up medical procedures, he borrows from relatives and neighbours.

The father, who now earns a living by looking over accounts at a fishing market for Tk 400 a day, knows that he cannot let up.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments