CONTINENTAL DRIFTER: SOLO TRAVELLER

Home:

Today, sitting on my balcony in Dhaka, with my face to the south looking down at the green neighbourhood park, I look back on my travels upon this earth. The tall trees and reddish shrubs and rows of blooming flowers charm my eyes. All rainbow colours merge in the light of the bright afternoon of the Bengali month of Falgun, spring season in this semi-tropical, lower riverine flatland of the Gangetic delta. The rains will come soon, in the month of Boishakh; April 14 will usher in the Bengali new year with a riot of colour and carnivalesque festivity on Pahela Boishakh.

Today, sunlit reflections make me recall how I have lived my life as a diasporic creature, a continental drifter to and from the Indian subcontinent. I have touched the blue waters and the mighty currents of the Indian, Arabian, Atlantic, and the Pacific oceans. The ebb and flow of moonlit waves have alternately swelled and soothed my soul in the years I have spent searching for my journey’s end.

As a child I have stood many a time on the steps and plinths of the majestic ruins of Mohenjo Daro and Harappa, while my love of history books ignited my imagination to fill the emptiness of the rooms and the courtyards and the granaries and the bathhouses and the adjoining fields with breathing men, women, and children. Even my dreams were peopled by sunburnt folk in white homespun cotton garments.

The Indian subcontinent is my geographical space, and I carry my Aryan-Dravidian colour and shape to the Occident and the Orient with pride. Bengal is my birthplace, with my roots firmly attached to the alluvial clay of East Bengal. I am the inheritor of a rich culture layered with trajectories of centuries of settlements by Persian and Greek and Arab and Portuguese and Dutch and British voyagers, traders, conquerors.

The bloodlines of the Bengali woman meet all cultures and languages, from the Hispanic to the Indic, from the Runic to the Hieroglyphic, from the Nubian to the Sumerian. The profile of the Bengali woman eludes the Cubist frame of Picasso; she is multiethnic, multidimensional, a racial chameleon, made from mud and terra-cotta, from bits and pieces of drifting Gondwanaland and effervescent Gandhara art.

In my travels around the globe, I have met many who have embraced me with their warmth and generosity. Once, at Heathrow, a beautiful, tall hijab-adorned lady, upon spotting me in the milieu in my long coat and trousers, suddenly came running up to me with a radiant smile and said, “La Arabia?” I smiled back and softly replied, “No, Bangladeshi.”

The light in our eyes and our smiles lingered in the air for a while, and then melted as we each turned towards our own boarding gates. I am fluent in four languages and can get by with a smattering of known words and phrases in a few more Romance tongues, but at that singular moment in time at Heathrow, I wished I had cultivated the art of conversational Arabic even though I can read the Quran and Arabic script.

My multi-ethnicity is not a mystery or cause for befuddlement for me. Rather, I am amused at the comedy of errors my Bangladeshi sisters and I end up re-enacting on the world’s stage. We all have anecdotes we love to share. In Canada, all the way from Nova Scotia to Ontario, with me in my long skirts and my long black hair, black-lined eyes and pale brown face, strangers kept asking me, “Are you Mexican?”.

Ironically, here in Dhaka too, I am often quizzed. Recently, lunching with an academic of the opposite gender at a conference in Hotel Sheraton, in my starched sari and matching crystal dangling earrings, chatting gaily in rapid-fire English, the chief waitress handed me the goblet of chilled fruit juice, smiled, hesitated, and shyly asked, “Are you, madam, perhaps Sri Lankan?”

Second Home:

Mornings in Melbourne are magical. The large picture window of my bedroom faces east. I wake up with the shrill whistling of songbirds, with the red-blue hue of dawn filtering in through the open slats of the Venetian blind. I look out at the green rolling hills, and trees as far as the eye can see. The new babe, my grandson, sleeps in his cot in his parents’ room, with the window on the west facing the small rectangular landscaped garden at the front. The sun’s slanted rays keep his room snug and warm in the late afternoon when the breeze crosses the ocean and cools the earth.

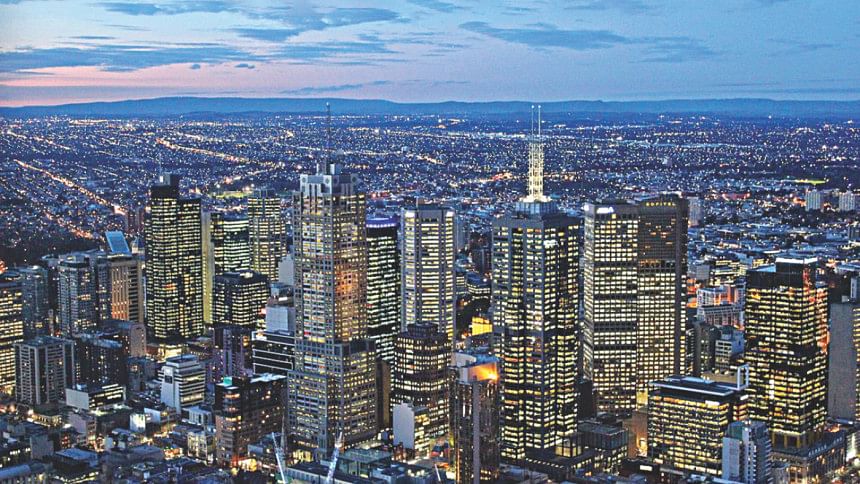

The city centre lies to the south. Standing on my toes on the freshly mowed grass in the large back lawn, I can look beyond the wooden fence and see the faint outline of the skyline of the business district. On clear, starry nights, the city lights sparkle, and the din of bustling activity is carried intermittently through the ether all the way to this quiet northern suburb of Craigieburn.

This is my fourth visit to Melbourne. On my first visit in March 2009 to attend my daughter’s graduation ceremony, I had stayed with her in a typically cozy old English-style rented house near La Trobe University in Bundoora. The house in Craigieburn is new, comfortably sprawling, open-style. I am grateful to my son-in-law for buying such a lovely home in a pastoral setting. My family knows I suffer from claustrophobia.

Seven leagues across the seas from the Tropic of Cancer, I wake up at dawn in the dewy darkness of an autumnal Sunday. At night, after a dinner of pure Bengali food, which I had cooked in plentiful quantity on Saturday morning—a working strategy to leave me two whole days for fun and frolic—I steep in an hour of delightful quality time with my daughter and son-in-law, surrounded by the stereophonic voices of singers auditioning for the televised talent show, The Voice.

A beautiful twenty-year-old girl sings a jazzy Peter Garrett number. One of the judges, Seal, is immediately possessed. He starts tapping with his neon nails on the metallic armchair with eyes closed, grooving with the music, and then gets up to sinuously jive to the beat as he matches the girl’s clear vocals. He chivalrously romances her into his team. My daughter and I are thrilled, and our eyes sizzle.

Earlier, on Saturday afternoon, I was out in the dazzling sunlight on Swanston St., sauntering in the midst of hundreds of every race and tribe of this world, sharing the collective joy of music and dance and paintings of the buskers on the street. And then, as I turned left on Bourke St., the music of the Andes made me stop. An Inca flute player, Beta Chinguel, clothed in his traditional native multi-coloured woven jacket, was miming his own compositions electronically streamed across the city square.

Enraptured by visions of snowy-capped peaks, my eyes beheld the heavenly veil of Chinguel’s breath upon the wood instrument. I sat down to soak in the cool sunlight and live the images of the South Amerindian landscape spontaneously flashing through my mind. As I sat on the wrought-iron bench, I recalled the vision of the Sierra Nevada range and San Francisco bay and Baja California and the blue Pacific I saw in 1995 as the airplane dipped to turn east towards Vanderbilt U., Tennessee, on my way back from UCLA.

On the train back to Craigieburn, memories of other delightful interludes carry me into the past and across the equator once more. I remembered stepping over John Grisham’s name metalled on the pavement in his hometown on Beale St. in Memphis as I glided to the husky, dusky voices of the Blues singers. I remembered how my breath came in soft sobs as I again heard Martin Luther King’s sermon “I Have a Dream” as I toured the motel where he was assassinated. I also remembered the electric shock of thrill, and gasped loudly with a sharp intake of breath, as the boat made a U-turn on Lake Michigan and I beheld the jewelled Chicago skyline one particular midnight.

Slight, slanting rain hits the window-pane as the wind rises with the red rim of sunrise visible on Monday morning. I make myself a mug of strong sweet Lipton tea and bite into a crackling ginger biscuit. Scenes from a rainy evening in Nagarkot in Nepal on Eid-ul-Fitr in 2010 surface as I gaze up at the clearing sky. I recall the redbrick colonial tea-house on a mountain ridge where my spouse and I watched the shimmering sunset.

Driving back to Kathmandu, for the entire duration of the journey down to the valley in Thamel, I had the thin sliver of the new crescent moon following me, with the car stereo soulfully offering me melodious, unforgettable golden oldies from Hindi movies of days of yore. My breath undulated as my lips formed each word of the lovely lyrics, my voice responding to the miracle of correspondence of time, space, lunar light, and immortal song. As we entered Thamel, mystical Tibetan Buddhist chants came over the airwaves from audio tapes.

Here, in Melbourne, what I miss most is the early morning muezzin’s call. I turn to YouTube and the soothing voices of Gregorian chants. I think of days passing, of meetings and partings, of places and distance, of age and decay. For a moment I falter, the pulse races. Quickly, I turn to caress my infant grandson’s soft, silky forehead. I lovingly hold him in my heart’s tight embrace, and my heartbeat regains its regular rhythm. I take a long deep breath as the first light of dawn beckons from the east. Inexplicably, a feeling of permanence, of continuity, of drifting peacefully, vertically, across space to the final continent beyond the earthly sphere, calms my mind. I am strong again, ready for the next journey.

Another Country:

The best of our young generation are thriving in Australia. More numbers of our young people are flocking to the shores of this continent. Why? The answer is obvious. Like birds flying away in panic from nesting tree-tops in the path of the eye of the storm, our young are fleeing the homeland to find new, peaceful nesting grounds. It is a tragedy for us, the parents, who are painfully embracing this separation in their declining years to give their progeny the opportunity to settle in cities where they can grow confident and strong in honest toil and just reward.

Soon, I fear, my native geographical space of East Bengal will be a country of old folk, with rural and urban spaces empty of the young and the brave. The young ones will be gone, some to thrive with diasporic multiethnic identities in distant lands, singing songs of the motherland, cooking the food and celebrating the culture of the homeland they chose to leave behind. Many others—in all likelihood the dispossessed and the unlettered, the marginalised and the landless poor—will be tragically lost in boatloads of illegal migrants. Refugees forever—nameless, naked, hungry. Floating, drifting, or drowning.

Epilogue: Beyond Borders

Sitting by the Yarra on ancient Aboriginal ground, the old woman—scholar, solo traveler—thinks of the land of her birth. She is alert and quietly still in the present, with the pupils of her eyes focused inward, engaged with unlocking the portal into her previous life in the Gangetic Delta. She is enfolded by the muddy, splashy energy of the paddy fields, in the furrows of the flat flood-plain. She is swept away by the waters of the snaky tributaries of the Jamuna and the Meghna. The dolphins of the Buriganga sing to her of the unique pink sheen of the pearls of the Bay of Bengal.

Rebecca Haque is Professor, Department of English, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments