Finding relief in skating

In Dhaka’s Korail slum, futures are made and unmade. It is bloated with vulnerabilities. Lack of basic living conditions, sudden fires, exposure to drugs like ‘dandy’, unhygienic atmosphere, monsoon rains, unruly goons, abusive neighbours, etc. are some of the factors that plague the lives of those unfortunate children who live there. Their present is prone to unexpected disasters, their future precarious.

Those kids are often misbehaved with. From shopkeepers to neighbours to their own parents, there are very few people who gaze at them with mercy. To them, getting slapped, beaten up or sexually abused, having meals in unhygienic conditions, defecating under the open sky, buying and sniffing ‘dandy’ from available places, working as messengers for those who frequent the slum in search of recreational drugs, blending with questionable peers, and dropping out of school aren’t unfamiliar. They know what it’s like to live a perilous life. They have experienced what most kids of their age are not supposed to. Many of them have intestinal worms, are anemic and suffer chronic fevers and infections due to the lack of proper sanitation and housing.

It is a humid Friday with no chances of torrential rainfall. I meet with Aysha Rahman Monica, Programme Director of Bangladesh Street Kids Aid (BSKA), near Titumir College. Her car is filled to the brim with skating materials—skateboards, helmets, jerseys, sports shoes, safety equipment.

With Aysha, there’s Sharmin, one of the skater kids, who lives on the streets. We wait for the others to join us. As they keep arriving—some wearing sandals, some barefoot—I notice how diverse their ages are. They range from four to thirteen.

When a timid Kulsum appears, I assume her to be a four-year-old. When I ask her mother, a plastic collector, about her age, she quips, a grin plastered on her face, “I don’t know. I don’t even know my own age.” I decide she is four. Anyone can claim so. Regardless, she is the youngest of the lot.

We load the food materials and gallons of water into the car’s trunk and wind up at Gulshan Lake Park. The place is replete with trees and greenery. Squirrels drift up and down the tall trees, shaliks and mynahs sing in the gardens, bats make surprise appearances intermittently in the sky above the cluster of betel nut trees.

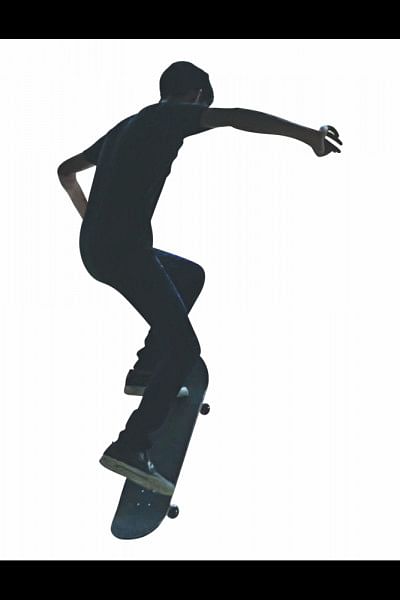

There’s an amphitheater-like open space, where we unwind. The kids put on their jerseys, shoes, and helmets, constantly supervised by Aysha. Before skating, they practice stretching, all assembled in two lines, following Aysha’s directions. Then they get on the skateboards and drift across the maroon ground, seamlessly balancing themselves, their bodies undulating, wind in their hair.

Onlookers observe their activity; some are awed by the talent they possess, which seems unexpected to them (the onlookers). Kulsum rides the board (which is of a little less height than her) well. She even manages to ride it on her back. The kids ride and fall, fall and ride. They don’t seem to be unnerved by the possibility of injuries, although Aysha keeps warning them to be careful.

Guardian-like to the 12 kids present today (usually they number 25), I often find Aysha forbidding them from spitting on the roads and convincing them to dump plastic and waste into available bins. She’s been affiliated with the cause for the past three years, after she noticed an event in Cox’s Bazar conducted by BSKA’s founder Susie Halsell, an American anthropology student at BRAC University who visits Bangladesh every year. Susie started BSKA in 2017 with a board of directors in California having five members. From 2007 to 2012, she taught skateboarding to the underprivileged kids (mostly) in Cox’s Bazar. She says a vision of seeing the kids progress at skateboarding and in life is what made her start BSKA.

I converse with Aysha about the health of those children. She says most of them are addicted to ‘dandy’. They have sniffed glue at least once in their lives. However, since the inception of Bangladesh Street Kids Aid, the rates of sniffing glue have lessened, from being constantly taught about the hazards that ‘dandy’ invites and how it can wreck their lives, both physically and financially. During the weekly skating sessions, they are given basic lessons on hygiene, alphabets, math, reading, writing, etc. The skating exercises also provide them with physical fitness and make them calculative and aware of their surroundings.

When asked about the reason behind the street children’s vulnerabilities, Susie says, “Their only social support (other street kids) often are bad influences on them and teach them how to smoke cigarettes or inhale glue, gas, and other chemicals in a polyethylene bag to get high. This offers instant relief from their stressful environment and relieves hunger pains but is extremely harmful to their internal organs and causes permanent memory loss.”

Both Susie and Aysha say these children need love more than anything. They have become habituated to constant abuse.

Relevant to this, Susie had to face disparaging statements like, “They’re not good kids, they take drugs,” “What’s the use in helping them?” Many people have given up on them. They declare them basket-cases and ignore them while going on about their own lives.

As for the future plans of BSKA, Sohail Ahmed, a freedom fighter, is going to allocate his plot for the children in Gazipur to build a skating park, where the kids will have shelters, healthy environment, basic necessities, and ample opportunities. Susie and Aysha are currently going through the process of establishing BSKA as an NGO.

Both believe that conducting weekly sessions is just a means of relief, not a permanent solution for the long run. A permanent solution will only emerge when efforts are taken by everyone, not just a selective few.

The sky has turned gunmetal, the clouds grumbling. We’re driven inside a patio as the heavens open, Aysha and the kids skateboarding their way inside. We pack everything up and have lunch inside, ready to leave when the rainfall subsides.

Aysha guides them to CNGs one by one, recording the drivers’ and the CNGs’ numbers, ensuring they reach safely. As the vehicles get packed and they, replete with satisfaction and delight, start singing, I look on. Their eyes show how different they become when they get to spend time in such a wholesome atmosphere, an atmosphere they deserve, but which has, in reality, become a luxury for selected people. One can look into their eyes and perceive how much joy, curiosity, sense of involvement, and passion it gives them, and how they don’t deserve to live inside cramped slums, exposed to plagues of various sorts, uncertainties and hazards stalking them as shadows.

They wave me goodbye and the vehicles whoosh past me. And I am left with this desire to join these little friends whenever I can during the weekly sessions.

Shah Tazrian Ashrafi is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments