The secret life of booksellers

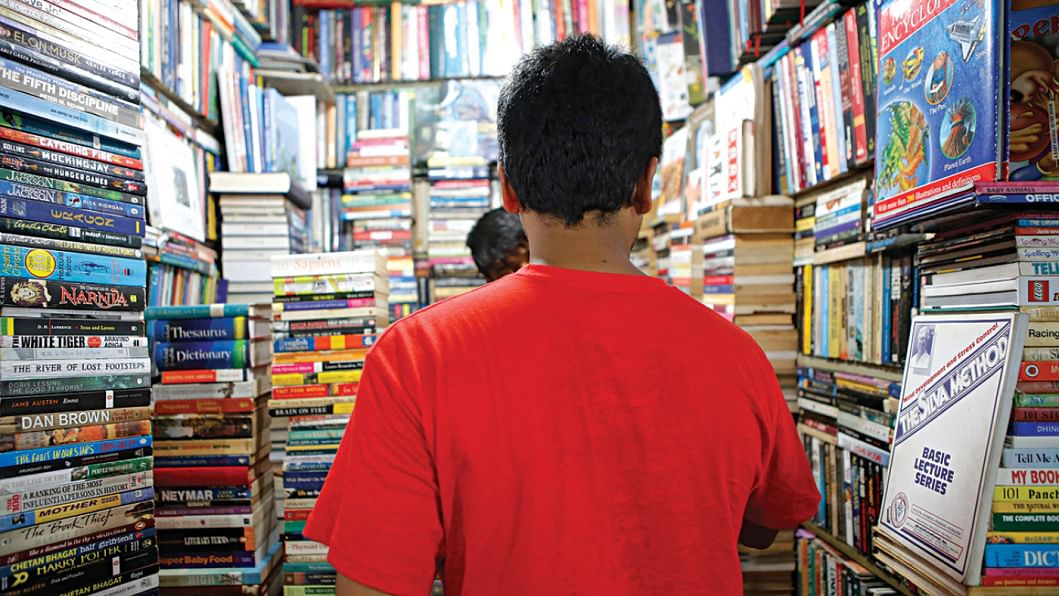

Petrichor is the word for when rain hits dry soil, releasing a fragrance almost impossible to describe—the earth smells wetter somehow; richer, browner, greener. It was petrichor I smelled as I roamed, shuffled, and tiptoed my way through rain-drenched parts of southern Dhaka this past Monday. But there’s another scent that grows stronger (or so it feels) when the city is covered in rain. As I bookstore-hopped through New Market, Nilkhet, Mohammadpur and Tejgaon, the smell of the books’ pages hung potent in the air. You could smell a whiff of something metallic from the grey textbook pages in New Market; Nilkhet’s second-hand paperbacks released more strongly their musty odours, and both Charcha and Bookworm Bangladesh smelled of fresh paper that you knew would feel clean and crisp in your hands. Surrounded by this aura on rainy Monday sat the curators familiar with every nook and cranny of these little stores, discussing passionately their love for the books they sell, for the respect and imagination and possibilities their work makes possible—the booksellers.

Why sell books?

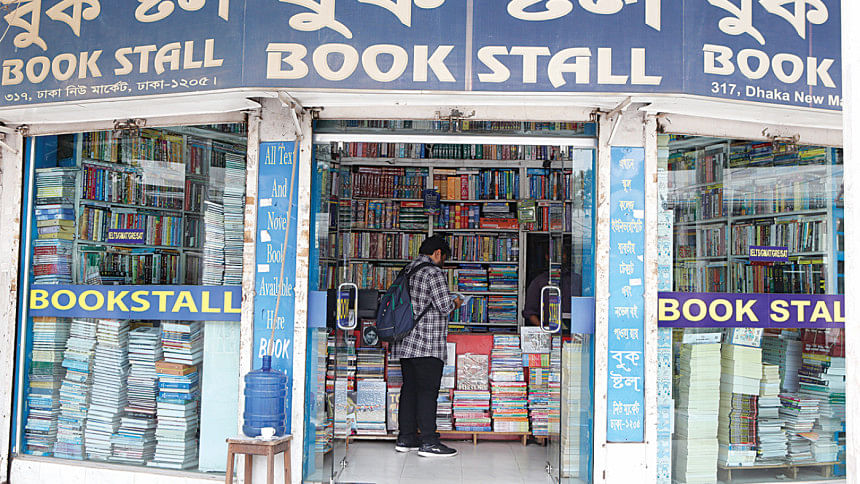

Nizamul Huq, 38, one of the salesmen at Book Stall in New Market, earns only around Tk 15,000-16,000 a month from his job, where he works six days a week. Muhammad Zakir Hossain, 42, owner of a tiny stall full to the brim with books in Nilkhet, doesn’t even keep a record of how much he makes each month. He just knows he has to pay rent by the 10th of each month and his daughters’ school fees by the 9th. Every month, he hopes for the best, sometimes managing to extend the school fee payment by an extra week or two. And Sabrina Islam, co-owner of Charcha bookstore in Mohammadpur, is constantly reminded of how niche a clientele her business serves, due to a serious dearth of book readers. All of these businesses were hampered by the arrival in Bangladesh of e-books, social media, online news portals and, in the case of Zakir whose business spans back decades, more television channels around 1998. And yet they all, situated across the city and the socioeconomic spectrum, assert the value of bookselling.

“I could have chosen to do anything else. But this work of mine has so much beauty, so much peace and discipline,” says Zakir, who lost his father and with him their financial stability when he was in Class Two, going on to sell magazines on sidewalks before finally opening his store in Nilkhet after he moved to Dhaka and married. Setting up the store required an investment of Tk 200,000. Zakir had only Tk 20,000 cash. He borrowed from his brother, from cousins, repaying them once business took off—all memories from a time when Nilkhet was uncrowded, but the entrance to his store would be crammed with readers waiting for him to open up every morning. Sadly, the situation has reversed now. Nonetheless, Zakir explains: “When we go to buy something from the sidewalk, we all but snap at the vendor. Ai beta, eta de, oita de. But my customers—students, professors and so many others—all call me Zakir Shaheb. A barely literate person such as myself caters to so many learned minds. We speak on the phone, I visit their houses to deliver books. The personal relationships you build in this line of work are beautiful.”

Charcha, nestled in a homely corner of Mohammadpur, and Bookworm Bangladesh, whose original branch has become akin to a tiny landmark on the Old Airport road, were both born of personal ties. Sabrina and Sabbir Bin Shams conceived Charcha at the suggestion of the latter with the specific purpose of selling “rare” books, such as long-forgotten classics, quality translations of non-Anglophone literature, uncommon non-fiction titles and genres, and obscure titles requested by hopeful readers. Their first branch opened ten years ago in a market in Katabon. Sabrina recalls mounting a van piled with books from Bangla bazaar (their supplier) to the venue in those days, shocking passerby. She recalls facing both encouragement, skepticism, and some uncomfortable male attention as a girl opening a bookstore at the age of 20. Today, Charcha’s shelves are inspired by an eclectic mix of the owners’ varied tastes, with Sabrina’s leaning more towards fiction and Sabbir’s towards non-fiction.

Bookworm was started in 1993 by the late Captain Taher Quddus, a book-lover, and still functions as a family business run mainly by his daughter-in-law Amina Rahman. She is helped by relative Ariz Hoque who looks after the store’s online communications and his father and freedom fighter Rafiqul Hoque, lovingly known by everyone who frequents the shop as “Rafiq Mama”.

“Books are integral to the collection of knowledge in a community,” Rafiq Mama explains when asked about the value of their work at Bookworm. “And it’s nice to stay up to date on regular customers’ lives, especially the slightly elderly ones,” Badal Mahamud, the store’s manager, adds with a laugh. Cleaning the cover of a textbook behind the counter, Nizamul of Book Stall, New Market gives a much briefer answer. “Boi toh ekta bhalo jinish.” He has worked in bookstores in New Market all his life and can’t imagine doing anything else simply because it’s all he’s ever known. I push to find out about daily frustrations, about what makes the job seem worthwhile despite the financial limitations. But he reiterates the same—“The book is such a good thing that no part of working with it can feel bad”—as if it were obvious.

The personal touch

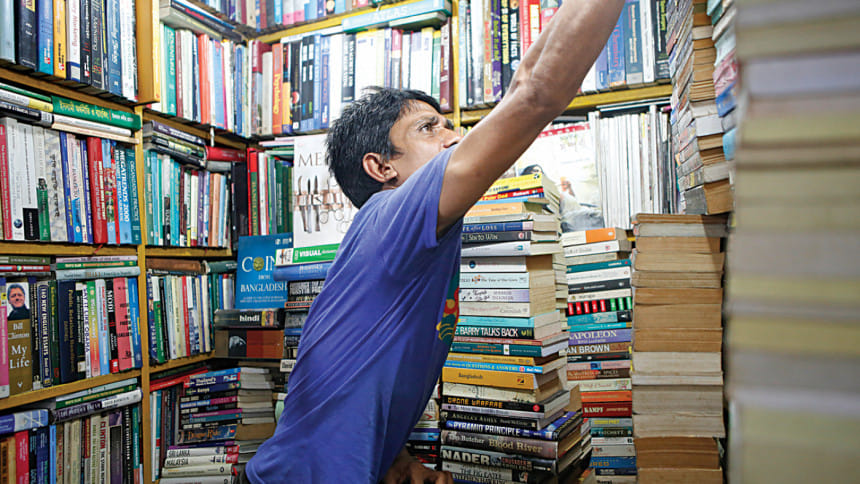

Midway through our chat, I ask Zakir if he has a copy of Stendahl’s The Red and the Black. He surveys the towers of books around us with intense concentration for a good two minutes, as if he can see through to the skeleton of his store. This is how he runs the shop. No lists, no records; titles and their locations live in his head as they shuffle their way across the stacks, and so often miss landing in the hands of a customer. Sometimes, Zakir calls a client back to tell them he has finally found the book they were seeking.

The staff at Bookworm, even though they rearrange their shelves often, preserve the general blueprint to help customers feel more at home. “Regular customers walk in and head straight to where their favourite genres rest. They’ll notice and point it out if we’ve changed something,” shares Rafiq Mama. Ariz adds, “Sometimes I’ll tell a customer we don’t have a copy of a certain book, and they’ll correct me and point me towards the exact shelf of the exact wall where the book is actually hiding.”

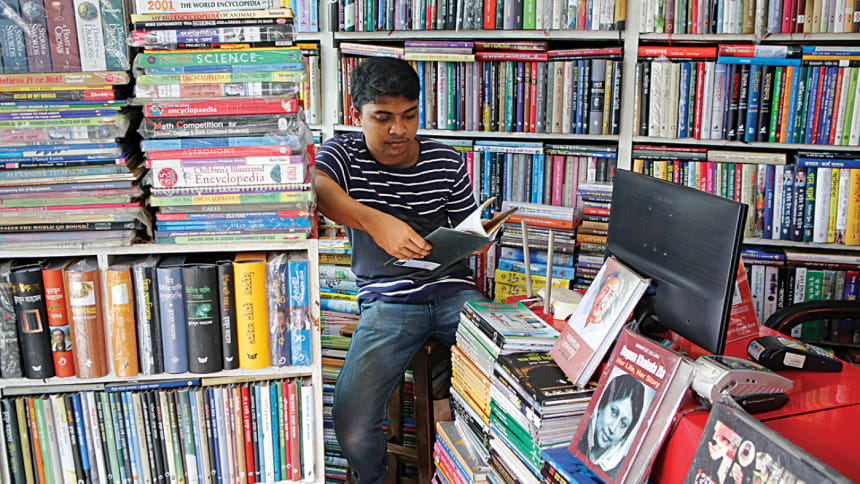

But what do these shelves mean to the sellers, who arrange and take care of them daily? At Charcha, while the first thought goes into making the book-searching process logical for customers, utilising common industry strategies like stationing dictionaries and other functional items at the billing counter to convey a certain message about the store, a certain sense of ownership, of personal beliefs and preferences, also comes into play. The staff knock heads over how to clean out the shelves—Sabrina prefers having it all down in a pile on the floor and starting from scratch, while Fateha Nisha and the other salespeople who spend more time handling the shelves day-to-day find the overhaul overwhelming. They group similar genres, authors, and categories together, but Sabrina makes it a point not to label these sections anywhere in the store. “I want readers to find their way through the books, discovering old favourites and new titles along the way,” she says. They’re also firm on a no-pictures policy within the premises. It’s strictly a place for reading books, discussing the arts, and forming personal connections, particularly for kids.

What does it take to be a bookseller?

I ask these people how working in the stores has affected them personally. Nizamul talks about getting to read books while at Book Stall—a few pages here and there every morning, when the crowds are thin. Dealing with customers, reading excerpts of books has helped Badal gather more knowledge on various subjects while at Bookworm. Ideologies travel with customers, and debating views has taught Ariz both to make friends and to agree to disagree with the customers of Bookworm. Mehedi, who can’t read but has the most number of Bookworm’s titles memorised from delivering them across Dhaka, enjoys how closely the job allows him to get to know the city. And Nisha, who spends the most amount of time with Charcha’s customers on a daily basis, is happiest because it has thrown open her knowledge of authors and genres, adding to her list of favourite books. Sabrina also highlights understanding the space of the bookstore to better understand the client base—while they sold more non-fiction and textbooks from their previous branch in Katabon, their cosy alcove in Mohammadpur attracts far more fiction-lovers.

And what, finally, does it take to do this job day in and day out, I ask them, in what is commonly known as a dying industry?

Memory, Nizamul tells me. You must remember what each customer prefers, what they looked for the last time they visited Book Stall. Ariz mentions both intuition and initiative—uploading lists of new stocks, replying to endless swaths of queries on time is a more technical task, but just as integral is the instinct that distinguishes between customers who want to chat, who want to be shown new books, and others who prefer to shop in silence. Sabrina brings up patience—staying calm as you notice your readership dwindling, and also when some customers try to haggle over the prices of high-quality hardbacks and paperbacks at the store, something Rafiq Mama agrees with as he shares stories of book covers left crinkled and tattered on some shelves. And yet for all of them, welcoming returning faces, discussing the books they sell, and hearing wildly different responses to the same books all make these minor hiccups seem worthwhile. “Some days, you might sell a hundred books. But in others, you might not even make Tk 100 from the day’s sales. People don’t come to buy books as much as they used to, before. But you power through based entirely on hope,” says Zakir before turning to a customer in his corner of Nilkhet.

Comments