“Poetry has given me everything!” – Al Mahmud

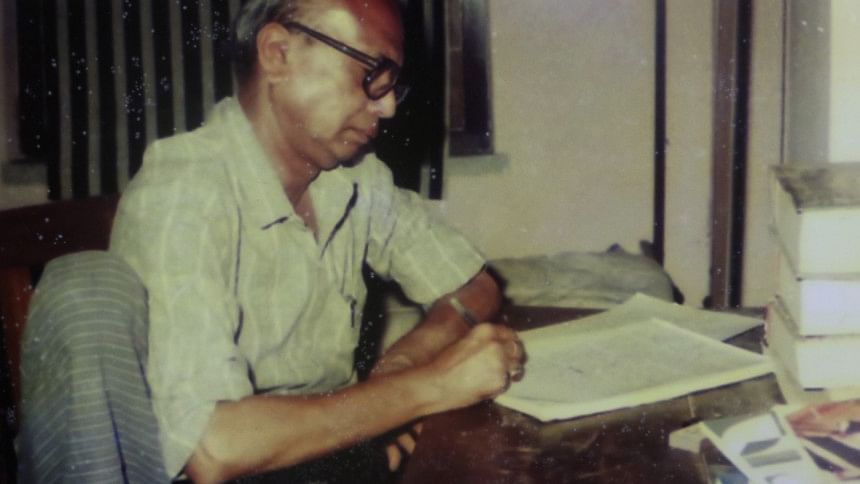

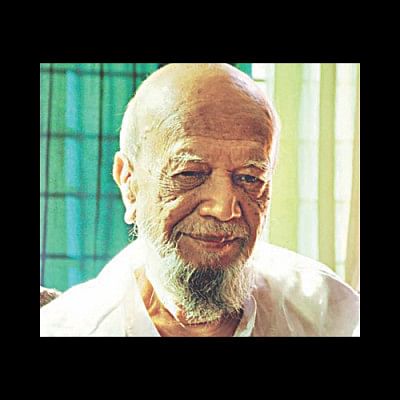

Al Mahmud lived a long life, witnessed an eventful past. One of the most renowned contemporary Bengali poets of his time, he spent a lifetime writing and appreciating poetry. The recent changes introduced to the present practice of poetry in Bangladesh are closely related to those of the poet himself. As observed from his constantly evolving poetic tendencies, he attempted to identify and therefore, portray the probable signs of change in the spirit of the age with great care and ambition, while at the same time eulogizing the flora and the fauna, the rivers and the women, the new and the tradition of Bengal as it is. Looking back at the time he began, his first book Lok Lokantor was published by his friends. After that, Sonali Kabin was well-received and much talked about among the Bengali readers and critics that later on eventually, took him to the pinnacle of fame. He further proved to be of remarkable versatility by writing short stories and novels for his readers and on the other side of Bengal, had even a movie made based on one of those stories. Overall, his creative oeuvre has made him a legend in Bengali literature, and in this interview his thoughts/beliefs regarding different aspects of liberal arts and life in general have been discussed:

Had you not been a poet, what would you be? I mean, why not try something else?

I believe I have said it several times earlier on that if I were not a poet, I would have been a singer. There was a time when my hometown was called the town of music since the environment was one of so- much favorable to such practices and performances. If I have to explain as in why poetry matters to me more than all nowadays, I have to admit to possess no other notable expertise over anything else other than writing and reading poetry. So, I decided to live every moment of my life with it, dedicating every bit of what I can claim to be mine to this form of art. Once I decided this, there was an instant upsurge of discontent from many, but I never thought of giving up and kept my head straight like a defiant tree in the middle of a heavy monsoon storm. Perhaps, the very strength to stand against these stumbling blocks says how I had no other choice but to become a poet.

You have come a long way from your village to Dhaka and become a poet, faced many adversities. If you would tell us about the stories behind the scene-

I remember coming to Dhaka in khaddar punjabi-pajamas and a pair of plastic sandals. I carried a ragged suitcase with me that had a red rose poorly carved on the front view. Certainly, I wanted to be a poet and have been living here in the city for many years. In my old worn-out suitcase did I carry once a dream of the entire Bangladesh along with all her rivers, birds, insects, boats, men, and women just the way magicians keep their secrets in a little box of magical tricks. I tried my best to unveil all that my poor suitcase had to offer; it made people applaud sometimes and sometimes brought them to tears. And as I realized my own dream in time, many a friends of mine carried with them "selected poems" from different European languages. Unfortunately, most of them just didn't have the luck as young readers in this metropolis do not even know their names. Having said that, what's important to remember here is that literature was never a thing of competition and it is not so even now. It was a phenomenon of joy and will continue to be so in the future.

Nowadays we see a culture of prose-writing gaining more momentum than that of poetry. What do you have to say about this?

Well, to speak the truth- while poetry has been accepted as the bedrock of literary practices in Bangladesh, prose has been a popular genre and a progressive one on that from the very beginning. From what I can see based on the recent few years though, the evolution of poetry you could say is very close to complete a certain stage of its modern formation in Bangladesh.

In one of your recent writings you said- "The world changes as does the dream of man." If so, how? And also, which one do you think comes first and is an absolute must in terms of creative writing, an eye to inspect or a heart to imagine?

Yes, true, the world does change as the dreams of man change. The changes in our perspectives, dreams, faith in humanism, science and what not. Altogether there is a mystical and yet-to-be-identified air about it all. I believe the science behind this phenomenon has not been truly documented yet by research, for it just might dawn on one all on a sudden. For example, a poet might find his prosodies, similes and metaphors one day and produce outstanding poetry out of it on the other.

If you ask me, no form of creative arts is about investigating systematic patterns (which is a completely different approach altogether) as much as it is about practicing your favorite modes of expression. Those who will do it with integrity, will be able to truly relish the taste of life. And for poetry especially, it's a lifelong commitment. Everything I feel or feel like saying has to be given the frame of a poem, where all my unspoken regards are realized in the truest way possible. Poetry has given me everything. I am who I am for the way I imagine- that's how I see it.

Poets from the West like Yeats, T.S. Eliot immensely influenced our poets in the 30's- which we can say about some of your works as well. Any thoughts on that?

The truth is, Emran, poets have to have a home. In that case, the ones from the 30's had none. They had to look for one and go somewhere, even though they did understand after a while that the answer might lie in the very roots of one's own. I mean, Buddhadev had to return to the Mahabharat, hadn't he? A poet who wakes up from his slumber at the smell of his own earth, perhaps, is of the best kind.

Since we are looking back, where were you during the Language Movement? And I heard you knew Bangabandhu on a personal level- is that true?

I was in the mofussil then, hadn't come to Dhaka yet. But the heat of the wave from Dhaka reached the villages and mofussils alike. A local committee for the Language Movement was formed in our little town, and in one of their leaflets they published a poem of mine titled "Februarir Ekush." Apparently, a warrant was issued in my name for the crime I had committed. I could not really stay home and soon after, fled to Dhaka.

As for your second question, I was the editor of Ganakantha back when Bangabandhu was around. It is true that he knew my uncle and some of my cousins and therefore, me since the time he visited Calcutta. But of course being the absent-minded man that I am, I don't remember the exact words from our conversations, whatever those might have been about.

Would you like to think yourself to be one of the best Bangladeshi poets of our generation as it has been argued numerous times?

I have been asked questions as such many a times before and every time, I counterpoised whether the very idea of pieces like Sonali Kabin being received by the majority of a readers' community should label me as "the best of my generation." It shouldn't! But of course, I do feel flattered when my works—the ones that accentuate my true poetic identity—are appreciated for what they are worth of. If you ask me, the power to decide here is solely up to time and none but time itself, for not all the "great poets" prove to pass the testament of time. Only time can tell who and what effort of theirs deserve to win immunity over our fleeting realm of nothingness.

Well, Mahmud bhai, soon you will be eighty years of age. And we know everyone alive has to face their end. Do you think over this universal truth quite often?

Actually, the thing is whenever I think of death—it's never a singular and precise awareness—but an obscure combination of many. You could say that the deaths of friends and relatives can leave one with a permanent intimidating image of death. I wasn't there when my father died and yet, this very experience gave me such hints of the divinity that whenever I remember the deaths of my dear ones, those hints prior to his departure become eminent in my memory. For me, this one instance of death points towards an eternal world where the journey will be all mine to have, remote and solitary.

Emran Mahfuz is a rising poet and works with the Daily Star Books. Motiur Rahman is a lecturer of English at Dhaka University of Engineering & Technology.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments