TRIBUTE: Every eulogy falls short

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, whose 44th death anniversary we observe today, stands tall among many heroes of history whose individual contributions have made their country and people great. However, as we delve deeper into what he did for us as a nation, as a people, as a culture, and as an economic entity, giving us self-confidence and pride of place -- both of which we desperately needed -- his uniqueness begins to stand out, making the world and us take a more serious look into what his murder on August 15, 1975, really meant.

In terms of providing leadership to liberate his own country, Sheikh Mujib can easily be compared to the likes of Sukarno, Josip Broz Tito and Si-mon Bolivar. Like Ho Chi Minh and Mao, he started at the grassroots, had a similar rapport with the ordinary people, and inspired in us a new sense of pride and self-confidence, igniting that crucial spark of courage to dream for freedom. As with Gandhi, Mujib’s preferred weapon of political struggle was non-violence till his hands were forced with the start of genocide on the Black Night of March 25, 1971.

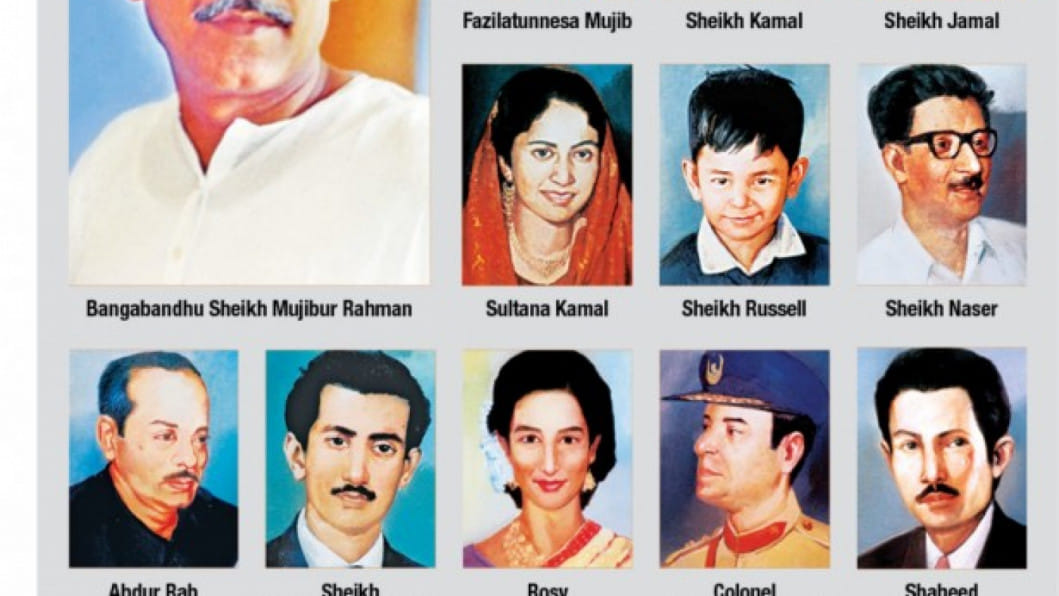

Just as in life, so also in his death Mujib stands unique. Few heroes of history met as tragic an end as Bangabandhu. Not only was he so brutally murdered but so also were all his family members except the two sisters, Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Rehana. The most heart-rending perhaps is the cold-blooded gunning down of his youngest child Russell, who was fired upon as his assailants were making fun of his pleas to go to his mother.

We know Gandhi was assassinated, so also were Kennedy, Indira, Bhut-to, Rajiv, Benazir, Allende. Sadly, world history has many leaders who were killed while in power or at the height of their popularity, but Bangabandhu was gunned down along with Begum Mujib, two sons, Sheikh Kamal and Sheikh Jamal with their newly-wedded wives, and the 10-year-old Russell. His brother, Sheikh Naser, was also killed at the same time.

Sheikh Moni, Bangabandhu’s nephew and an important figure of our Lib-eration War, was killed along with his wife, who was pregnant.

Bangabandhu’s brother-in-law Abdur Rab Serniabat was killed along with Baby, his 15-year-old daughter; Arif, 11-year-old son; Sukanta, 4-year-old grandson; and Shaheed, 35-year-old nephew. Rintu, an 18-year-old, who was not a member of the family but just happened to be in the house, had to die as well.

A total of 17 members of Bangabandhu’s family and extended family were killed on that fateful night in three different houses -- two in Dhan-mondi and one around Minto Road -- showing how well-planned and co-ordinated the assassins’ operation was and proving the massive and inexplicable nature of intelligence failure.

The murder of women, children, expecting mother, newly-wedded brides as well as random people speak both of the brutality and the cavalier na-ture of the entire killing mission. It was as if “death” was what they were after. They made no effort to distinguish who they were killing and why. They were like mercenaries who had accepted the job of killing and cared little as to who were dying from their relentless bullets.

We, who have lived through that dark night, were soon to realise the true meaning of Bangabandhu’s demise. It was the beginning of a con-certed attempt to undo 1971 -- what our Liberation War was all about. It was the beginning of the usurpation of the narrative of our struggle, of our slogans, processions, street fights with the police, of our Language Movement, of the various other movements that our valiant students and people in general carried out over the years -- of the very meaning as to why so many of our martyrs made the supreme sacrifice. It was the beginning of the denigration of our freedom fighters, of questioning as to what happened and did not happen during those nightmarish nine months of captivity of our body and soul.

If 1952 was an attempt by the Pakistanis to deprive us of our mother tongue, then 1975 was the beginning of an attempt to deprive us of that crucial “narrative” that gave us confidence, pride, self-respect and, most importantly, courage to tell the world in 1971 that we demand freedom, we demand respect and we will work supremely hard to prove that we deserve both by liberating our country.

Since so much of the commemoration of August 15 is government-sponsored, many people now neglect observing the occasion on their own. Government commemoration will last only as long as the government does it.

But in my view, Bangabandhu and his tragic death must be commemorated in our hearts and in our minds, individually as well as collectively.

In our hearts we must feel what he did for us -- the years in prison, the lifetime of struggle, the relentless articulation of the rights of the Bangalees, the uncompromising stances he took over the years and decades and the confidence he invoked in our hearts as someone who will always stand by us, regardless of the temptations and threats.

In our minds we must truly understand the significance of his actions that led to an independent Bangladesh. Because we have it and got it in a span of nine months -- though with an enormous sacrifice -- we perhaps don’t fully realise what it means to have a country that is free and independent and one that we can all call our own. We can look at a map of the world and point to one spot and shout, “This place is mine”. What a pleasure, what a thrill!

Because we have a country of our own, we are able to flourish in the many ways that we are doing (not to forget the many areas in which we are yet to). Be it in business, agriculture, the various sectors of the SDGs, we are attracting the attention of the world only because we have an independent country which gives us the opportunity to flourish.

Everything that has happened and is happening is because we are a free people with an independent country, and it is Bangabandhu who led us to that freedom and independence by uniting us, motivating us, energising us, disciplining us, making us emboldened, and when the moment arrived, calling upon us to wage our War of Liberation.

It was such a giant who was slain on August 15. Hence, every eulogy falls short.

Mahfuz Anam is Editor and Publisher, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments