OFF THE BEATEN TRACK

A tiny red gate jostles for space among shops, apartments, and the flurry of traffic in Block F of Lalmatia in Dhaka. Like the name pasted on its small billboard—Shunno—the first impression you get of this place is that of a blank or zero space, seemingly inconsequential enough that you don't really know what to expect. Upon creaking the door open, you find yourself in a narrow, winding tunnel that halts—suddenly—to present a vivid green alcove. Leaves and vines drape over each other, hanging in clumps, brushing against your head as you take in the dapples of yellow light. The tiny forest lies fenced in by a maze of other small rooms—a gallery space, a mini-library, a storeroom housing printmaking equipment, and a meeting/activity room modestly furnished with a long desk and chairs. The space feels truly secluded, inviting in little if any noise at all from the ruckus outside.

Such an absence of noise is hardly rare in what we think of as art spaces. The biggest of galleries, after all, contain at most hushed murmurs and the quiet shuffle of feet as visitors make their way through the displays. This is true of most of the big art names in our country including the Bengal Arts Foundation, Alliance Française, the Samdani Art Foundation, the Edge galleries, and of course the hallowed halls of Shilpakala Academy. These places all serve the important functions of accommodating a vast number of art and audiences in a sophisticated, climate-controlled, and spacious environment, made possible through a generous store of funding.

But in some other pockets around the city, art behaves a little differently. It explores new form and content, engages names that are less revered by the art world, and communicates with the artist, the audience, and the community, in more interactive and malleable ways.

New visions

"Kalakendra was meant to be a non-profit, artist-run space for art," shares painter, printmaker and sculptor Wakilur Rahman, one of the artists who came together to form the centre in Mohammadpur in 2015. The space was founded upon a collective realisation that it would be far more exciting to get out of their respective studios and work in tandem, particularly to see how new and younger faces are trying to create new languages through art.

"Private galleries function as per the demands of a dedicated market. We wanted to find people interested in a serious practice of art outside of such markets," he explains. Kalakendra scopes out and invites such artists free of rent to participate in curated, four week-long exhibitions every month. The exhibitions are supplemented by artist talks and discussion sessions (53 so far) that often include experts from neighbouring artistic fields such as filmmaking and even literature.

The spaces all share similar origin stories. In some variation or another, a group of creative individuals noticed a gap, a niche lacking in the local art scene, and sought to fill it through modest self-sponsorship.

Britto Arts Trust, a huge name in the art world today, started out in 2002 to "create a platform for the practice and research of experimental art, art with new attitudes." Mahbubur Rahman, visual artist and co-curator at Britto, addresses how art institutions in Bangladesh have historically had to operate in the mainstream. Galleries prioritised Modernist paintings. Even while Britto was being established, the major departments and galleries in the country remained confined within certain media while the global art scene left them behind, incorporating installations, performances, photography-based work, and site-specific work.

Since starting out, the Green Road-based premises of Britto have branched out to host national and international workshops involving video art, performance art, and new media festivals, participating in huge events such as the Dhaka Art Summit, Chobi Mela, and the Venice Biennale.

"A certain kind of art or artists are popular in the mainstream market. We ignore these tags of 'new' or 'old' or 'famous' when an artist approaches us. We focus on what is new in art and what it communicates to us," shares Manan Morshed, artist and chairman of the 180 Degrees art platform, a part of which is Dwip Gallery in Lalmatia.

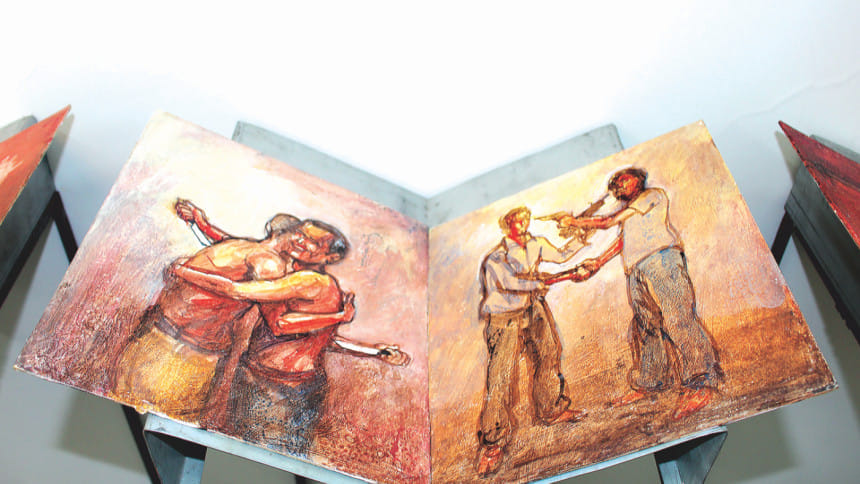

Art critic Mustafa Zaman, who is also chief curator at Dwip, elaborates further. "In comparison to Kalakendra, which steers clear of the conventional market, we want to draw the attention of the mainstream to experimental work being done by new and established artists. I've seen many artists who started out doing interesting work, but eventually gave in to more commercial demands like animals and landscapes. We wanted to preserve and create a market for the unconventional, particularly because such practices attract such little funding," he explains, using the example of Sanjoy Chakraborty's Laal Kono Rong Noy, which ran at Dwip last month.

This policy allows Dwip to offer a wide spectrum of arts and artists. In the same space, visitors of Dwip get to interact with works of both established names such as Wakilur Rahman, and newer names like Moon Rahman—a mother and homemaker from Feni, or Shamset Tabrejee—originally a poet.

A place like Shunno, meanwhile, was conceived in 2005 when artist Jafar Iqbal noticed the absence of a proper printmaking studio in Dhaka.

"People think of printmaking as a secondary form. By art, we automatically tend to think of oil paintings, watercolours, drawings, etc. I wanted to create a space that would provide artists with the paper, colour, other materials and the authentication certificate. It would be a collaborative process with an equal split of returns for the gallery and the artist, without charging any rent," Iqbal shares.

Over the past two years and after running around 100 workshops, Shunno has been dabbling in community and educational projects involving non-artists. Monoprint camps are held on weekends—the studio will demonstrate one print and participants follow suit, working on the same table and equipment as experienced artists, usually using discarded materials. The activity engages amateurs who claim they have no drawing or academic skills and that they don't understand abstract art, resulting in creative accidents that are both therapeutic and instructive.

Why space matters

"You have to go through a driveway, a daunting entrance, and metal detectors in order to enter the bigger galleries around the city [for obvious reasons of security]," Manan Morshed points out. While we sit talking at Dwip, high school and college students from the neighbourhood constantly move into and out of the single-storey building. They hang out right outside the gates, share cups of tea, and stroll in to take a look at the paintings on display while happily chatting away. All are dressed casually, some even in school uniform and carrying backpacks. None of them seem to hesitate even for a second before stepping into the gallery.

A vaunted gallery space can have an infantilising effect on a visitor, especially the young and the less formally-educated. It's easy to feel scruffy, to feel like you're simply not equipped to make sense of the art on display. In such places, the volume of the white cube and the gallery's prestige erects a barrier between the art and the audience. These are the blocks that a small establishment such as Dwip can crack through even while exhibiting art in the traditional gallery format.

As artist-curator Shehzad Chowdhury, the brains behind Longitude Latitude (LL) and several other pop up art initiatives, explains, however, "Space isn't always a physical space. It's a dimension that's in your consciousness, where the magic happens as you're transformed by an artwork. But space does shape your experience with it. It's ultimately about how we get people to experience a space that is beyond everyday mundanity. How do we make that space talk to the audience? That is the artist and the curator's challenge."

Since 2000, the LL events have brought over 100 musicians, visual artists, and even children and regular people under one platform, all creating and participating in artistic pursuits. There are workshops and talks by artists that are rarely accessible to the public otherwise. Some—like the seventh edition which took place in Cox's Bazar—incorporated local myths and the character of the physical surroundings.

"When I visit a pop-up art site, I ask myself why is this here? What is it saying? Is it serving the owner of the organisation, or the artist? So pop up spaces are like little fires that spread stories and disrupt the institution within a complex physical system. They should respond to their surrounding and create a certain energy, a shift in paradigm and a ripple of transformation—of the soul, of attitudes—in the society," Chowdhury explains.

What's still missing?

Despite their wildly different forms and content, most of these art spaces agree on a common set of absences in the local art scene.

While setting up Shunno, Jafar Iqbal felt the dearth of any standard policies for the establishment of such projects, particularly for a printmaking studio. There aren't enough contracting and legal services for artists and galleries, he says.

Curatorial expertise is also few and far between; besides the most well-known names, those who do curate do so out of personal interest in the field, often free of cost. Some exhibitions can perform poorly simply due to a lack of informed curation, even if the art itself is interesting. Places such as Britto, Kalakendra and Dwip were born out of the need to be able to play with space—painting a wall, hammering in nails, setting up audio-visuals over a long period of time, changing the very structure of a room—which are often costly and impossible to get at the bigger galleries.

Renting out and making changes to the gallery space takes up almost 30 to 40 percent of the cost of putting up an exhibition. By offering their spaces rent-free and allowing them to be altered without additional fees, these spaces arm struggling artists with a certain courage and motivation. Despite their financial limitations, their creative visions can manifest in interesting physical formats.

"However, the artist must also wrest the right to shape the space that way through his vision, his quality of work," Shehzad Chowdhury acknowledges.

He also calls out the lack of art connoisseurs. "People who make art and those who instigate these events need a stronger rapport. Without that, something as simple as getting a space becomes difficult. Curators need to make curatorial decisions that are more welcoming to different kinds of audiences." Wakilur Rahman highlights a similar problem—Kalakendra invites artists' friends and co-artists to introduce their work at an exhibition because they have a more meaningful insight into it. But the absence of famous names fails to attract the interest of the media and the larger art circle.

Mahbubur Rahman emphasises the issues involved in taking Bangladeshi art abroad. "The procedures involving customs, clearance, permissions from the Export Import Bureau and the Cultural Ministry, are all extremely cumbersome and expensive. If an organisation manages to take local art through these processes abroad once, they'll hesitate to try it a second time." He also calls for a more effective distribution of funding into local art practices to support new and struggling artists.

"Bangladesh is on the cusp of massive transformation. So the question is how we'll shift from the way we used to interact with the old spaces in our country, and how we'll interact with the new. Art plays a part here," states Shehzad Chowdhury.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments