Nation, Identity and Alternative Bangla Cinema: Conversing with Tanvir Mokammel (Part 1)

Editor's Note

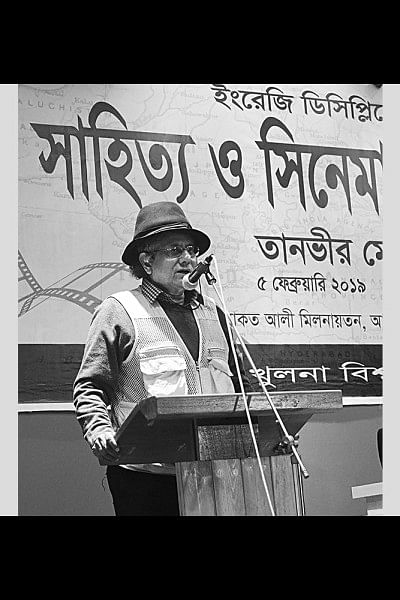

Tanvir Mokammel hails from Khulna, which is also the workplace of Prof. Sabiha Huq. This past February, when he was in Khulna for the launching of his partition novel Kirtinasha, the English Department of Khulna University became the privileged venue for a talk on cinematography. This event coincided with Prof. Huq's writing of a book chapter on media, and it was a wonderful opportunity to have Mokammel's views at length. An email conversation began and Tanvir Mokammel graciously addressed her questions on his life and career. The Star Literature Team presents the salient portions of the interview.

Amidst the pervasive outreach of cultural studies, the role of cinema and its disciplinary relevance to larger issues of identity formation are a given situation as it were. In post-independence Bangladesh, narratives on celluloid have created abiding and often contestatory discourses of nationhood and Bengali identity. To talk of alternative cinema in Bangladesh is to naturally talk of Tanvir Mokammel, and of late Tareque Masud, both being directors whose contributions have enriched the genre and thereby our culture-scape. A sensitive aesthete whose artistic career is shaped essentially out of his syncretic Bengali identity, Tanvir Mokammel's major concern over the years has been the complicated history of Bangladesh, and the shaping of Bengali nationalism. Mokammel's oeuvre makes him a remarkable source of inspiration for connoisseurs of cultural studies with an eye on the South Asian scenario.

SH: You have been an exponent of alternative cinema. What inspired you to make films in the alternative stream – the urge to find/say something more, or is it that you've found mainstream cinema inadequate in certain aspects?

TM: The answer can be both. Definitely, inadequacy of our mainstream cinema was the raison-de-etre that initiated me on the path of alternative filmmaking. To me cinema is an art form, not business. It is no longer possible in today's mainstream filmdom of Bangladesh to create any quality art. Even in my youth, I noticed the limitations of the mainstream commercial cinema of Bangladesh. So it became incumbent for me to embrace the alternative genre, and distribute those films through alternative means. Even my first venture, a short film Hooliya, was in the alternative genre.

SH: What according to you is Bengali-ness, and how do you trace this aspect amidst the contemporary wave of global capital?

TM: You see that throughout history the very concept of "Bengali-ness" has gone through a big change. You may remember the football match between "the Bengalis" and "the Muslims" in Saratchandra's novel Srikanta, as early as the first quarter of the last century, when Muslims were the majority in Bengal! Even today, to many people in West Bengal, "Bengali" means Hindu Bengalis only. There are others who believe that Bengali-ness will survive in Bangladesh only because of the language factor, even though the majority of the population is Muslim. So, you see the very term "Bengali-ness" can be a misnomer at times. A nation can be defined in different ways, but I think the quintessence of Bengali-ness is the Bangla language. I believe a Bengali is one who speaks and dreams in Bangla, and is steeped in the thousand years of Bengali culture. Bengali culture is rich and the civilisation is an ancient one, and so, despite globalisation the Bengali-ness of the Bengalis as a nation will always remain, at least among a large section of the population.

SH: You just mentioned "nation." What are the fine lines between nation and state? How do your protagonists take on this negotiation?

TM: As I see it, the state is temporal – it is created, it changes, and even dies. In Bangladesh there are people in most of our families who have lived under three states- British India, Pakistan and then Bangladesh. A nation however is something permanent. A nation may have many components like common language, ethnicity, religion, history, epic, and heroes; but it is historically proven that language ultimately remains pivotal to the formation of a nation. Community and nation again are not the same. They never were. Communities are based on religion, but nationhood is secular. It is generally based on language, and is usually composed of different communities. The example of the Bengali Muslims of East Bengal can be a perfect case in point. It was the language issue in 1952 that made the Bengali Muslims recognise their true identity, their de facto nationhood, that we are Bengalis. They learnt the hard way that they were Bengalis first, not Muslims, as the Pakistani ruling faction wanted them to believe. My film Nadir Naam Madhumati (The River Named Madhumati) takes up this issue poignantly. The young freedom fighter Bacchu has killed his pro-Pakistani Islamist uncle (his father figure as well, you can call it a Hamlet-situation) and in the final scene, he kneels down beside a river and the sound track plays "This Padma, this Meghna, this Jamuna/ this is my country." The Liberation War of 1971 and the creation of the state of Bangladesh was a "homecoming" for the Bengali Muslims putting behind their fallacious Muslim identity of nationhood during the Pakistani era.

SH: You have profusely made both documentaries and feature films. How do you reconcile between the two modes?

TM: As an artist my job is to explore, to find and to uphold the true essence of life. You can recreate the truth of life in a fiction film with the right script, right locale, correct props and perfect mise-e-scenes and can recreate the essence of reality to quite some extent. But in documentary you can reach the truth more directly and in more detailed ways. In Bangladesh, with its abject poverty, limited democracy, social and political anomalies, and lack of rights of the disempowered and the marginalized sections, there is no dearth of subjects for quality documentary films. Rather the country is a gold mine for the genre of documentary cinema. I always try to make a documentary film after completing a fiction. Though people say my fiction films are realistic, I know I have written the script; props and dresses have been collected, some actors play the roles and utter the lines, so somehow a tint of artificiality creeps into any fiction film. In making such fictions back to back, you may end up being too airy and lose connectivity with reality. But when you make a documentary you are perforce back to the raw reality of life. I believe, it is very important for an artist to remain connected with his everyday reality, with his society and the state he lives in, and to remain rooted in his soil.

SH: To talk of realistic settings, rivers and life on them have figured in a major way in your work, whether the much acclaimed Nadir Naam Madhumati and Chitra Nadir Pare, or documentaries like Oie Jamuna and Bonojatri. What is your perception of rivers and riverine life in Bangladesh?

TM: Bangladesh is a riverine terrain, and in every ten kilometers or so you will come across a river. Some of the world's largest and major rivers flow through our delta towards their estuaries. Historically, our towns and villages have grown up beside the rivers that were the main mode of transportation. You can say that our civilisation was based on the rivers. Besides, rivers are aesthetically very charming, with unique beauty in summer, in monsoon, and in winter too. Even within a single day, a river offers varying beauty in the morning, in the afternoon and in the evening! As a visual artist, I am immensely attracted to this sublime beauty of rivers, so they figure a lot in my films, sometimes consciously, and unconsciously at others. There is a philosophic angle as well in the unceasing flow of rivers, notwithstanding happenings around it. In this stoic nature of rivers, I find a resemblance with the flow of life itself. Hence I am pretty much attracted to rivers and I guess it will remain so till my last day. To round off this point, you see I own no land, have no house or even a flat, but I do have a boat. In fact I spend quite some of my time on this boat!

SH: I have always been curious about the historical basis of the oath taken by the freedom fighters that you have used in Nadir Naam Madhumati. Could you please elaborate on that?

TM: Only in the months of June-July after the Muktibahini was organised under the Mujibnagar government and sectors and sub-sectors were formed under the professional military leadership, the oath taken by the freedom fighters became formalised and an identical one. But before that, during the phase of early resistance, different local commanders were conducting oaths with different wordings. In Nadir Naam Madhumati the oath taken by Bachchu and his comrades under commander Maznu, a local guerilla unit commander, was such a one-off thing.

SH: Lalon, 1947/71, Hindu Dalit, ethnic tribes, the garment industry – your films have every element of diversity that Bangladesh is all about. How do you conceive of our country as an ethno-geopolitical locale?

TM: Even with its limited land mass, Bangladesh is a country of variegated nature. There are quite a few indigenous peoples, religious communities and sects, different and diverse ways of livelihood. Besides, though mostly a peasant society, Bangladesh is now stepping into the world of industrialisation. As a film-maker these diversities attract me. I like to portray the lives of those who are ethnically and culturally 'different', and who have been marginalised by the state or by the majoritarianism of the ruling class. I might mention the Bauls, the Chakmas and other ethnic minorities of Chittagong Hill Tracts, or the lower caste Hindu Dalits. It is sad that while Bangladesh was liberated with secular chants like: "Hindus of Bengal/ Buddhists of Bengal/ Muslims of Bengal /We all are Bengalis"; it is fast becoming a country of the Muslims only! That was never the idea of our Liberation war. I always believe you cannot make a garden with only one kind of flower. The culture of a country can be rich only with the presence and participation of different communities with their variegated cultural traits. This pluralism is needed for the healthy development of the democratic values in our society.

Sabiha Huq is Professor of English at Khulna University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments