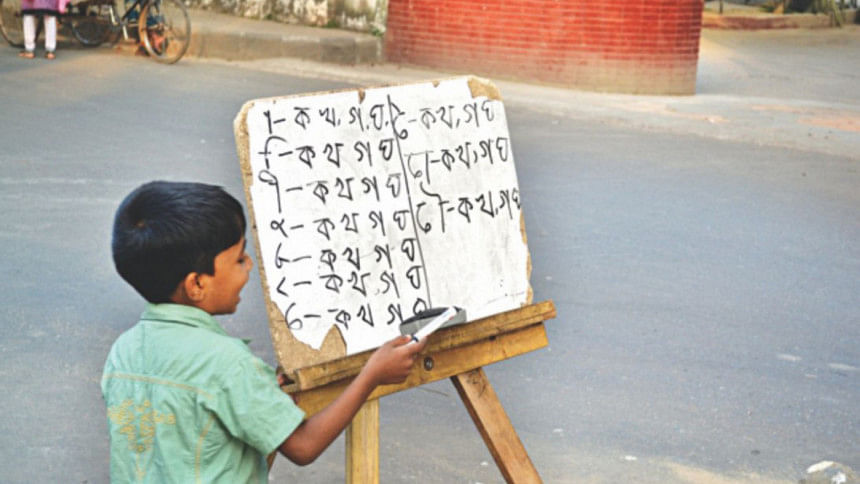

Achieving universal literacy status: How far have we progressed?

Right after the country's independence, when the literacy rate in the country was 16.8 percent (according to UNICEF), a group of young people in Kochubari-Krishtopur, a village of Thakurgaon, started a movement to make all the villagers literate. What they did was amazing: they taught every man and woman in the village how to sign their names and introduced the Bangla alphabets to them. After three months of continuous efforts, they succeeded in making all the villagers literate; they were all able to sign their names. Therefore, it was declared the first village in the country to come out of the curse of illiteracy (Prothom Alo, September, 2014).

Needless to say, the ability to sign one's name doesn't necessarily make one literate. Literacy means a lot more than that. According to Unesco's definition of literacy, a person is considered literate when they are able to read, write, and do basic arithmetic.

Forty-eight years ago, the villagers of Kochubari-Krishtopur understood that without achieving literacy, achieving economic prosperity would only remain a dream. Teaching the villagers to sign their names was the first step towards making them educated. Had the spirit of that movement spread across the country, we would have achieved 100 percent literacy a long time ago. But what is so depressing is that the literacy rate in Thakurgaon now stands at only 52 percent.

According to Bangladesh Sample Vital Statistics 2018, released by Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, the literacy rate for people aged 15 and above stands at 73.9 percent. This means that around 26 percent adults in the country are still illiterate. The increase in the literacy rate is nowhere near satisfactory since we were hoping to achieve 100 percent literacy by 2014. The ruling Awami League government in its 2008 election manifesto had promised to eradicate illiteracy from the country by 2014. Now it's 2019 and we still have a long way to go.

Unfortunately, all our neighbouring countries have a higher literacy rate than ours. Among the South Asian nations, only Afghanistan and Pakistan are behind us in terms of literacy rate.

A lack of government initiatives for adult education, mismanagement in education projects, absence of sustainable planning, resource constraints, as well as the inefficiency of the agencies concerned, mostly the Bureau of Non-Formal Education (BNFE), are to blame for the slow progress in our literacy rate.

Unavailability of funds to run literacy projects has been a major issue for the government. Donors are mostly not interested to fund such projects because of the mismanagement in previous projects. As this daily reported, in 2009, the AL-led government planned to take up two Tk 3,000-crore projects and sought assistance from donors. But it had to shelve the projects as none of the donors agreed to fund the projects. So in 2014, by the year we should have achieved 100 percent literacy rate, the government took up a Tk 453-crore project with its own funds to make some 45 lakh people aged between 15 and 45 literate. The Daily Star reported on September 8 that the project is now in crisis because of fund crunch and mismanagement and only one-third of the project has been implemented until now.

Clearly, the literacy-based programmes of the government have not been able to yield results because of the project-based nature of the programmes. As Rasheda K Chowdury, executive director, Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE), in an interview with The Daily Star in 2015 observed: "After a project is undertaken and one phase of the project is over, it takes about one to two years for the next phase to be implemented because of bureaucratic reasons. When this phase eventually starts, participants tend to forget everything that they have learnt in the meantime and we are back to square one."

Educationists and policymakers have been stressing the need for increasing the education budget from two percent of the GDP to six percent. In other words, they are saying that 15 to 20 percent of the national budget has to be spent for education. But unfortunately, our education budget has been trapped in the two percent category for many years now. With this meagre budget for education, undertaking the much-needed programmes for adult education is not possible.

There is another aspect of this literacy rate that we hardly talk about: whether this 73.9 percent population are actually able to read, write and solve basic arithmetical problems. We know for a fact that the expansion of formal education played a vital role in the increase in literacy, as the enrolment and completion rates at the primary level have increased in the last decade. But studies suggest that a big percentage of the primary level students do not have the basic literacy skills.

A 2018 World Vision Bangladesh (WVB) study found that 54 percent third graders do not understand what they are reading. WVB conducted the study in 51 government primary schools across the country and found that around 21 percent of grade-III students cannot recognise most common words and letters. Around 33 percent students cannot read five words in 30 seconds, and only 46 percent students read with comprehension. Another CAMPE survey in 2016 found that 32 percent students could not read, write or do basic arithmetic even after passing grade-V.

We surely have come a long way in terms of achieving literacy, from only signing names to learning to read, write and do basic maths, but there still remain some gaps that need to be addressed. For instance, the government's literacy-based programmes should not be project-based but long-term. And instead of depending totally on donor funding, such programmes should be run by the government's own fund. And that can only be done with an increased budget for education.

Also, the mismanagement and corruption in the adult literacy projects should be checked. We must make sure that the money spent for these projects is not wasted because of the inefficiency of the agencies concerned.

And most importantly, while working for increasing the literacy rate, we should focus more on quality rather than quantity. While achieving 100 percent literacy rate should be our primary goal, ensuring that those who are considered literate actually have the three basic skills which they can use in their everyday life, should also be our priority.

Naznin Tithi is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments