Substantial progress seen, but challenges remain

From paper-based and lengthy process, Bangladesh’s public procurement transformed into an efficient online system. Among various reforms undertaken by the government of Bangladesh, the transformation of the public procurement system stands out as a remarkable success. Let us explore what enabled such notable transformation.

Public procurement is among the most significant issues affecting public sector performance. Bangladesh spends annually about $18 billion, about one-third of its national budget, on public procurement of which about $16 billion is spent for development programmes.

Recognising the importance of public procurement, for over a decade, Bangladesh has been making continuous efforts to bring about a systemic change in public procurement environment. In the early 2000s, governance and institutional constraints were identified as serious impediments to growth. According to the World Bank’s Country Procurement Assessment Report 2002, opaque public procurement practices with protracted bureaucratic procedures resulted in low quality service delivery and lack of public trust.

The government embarked on a holistic, sequenced approach rather than ad hoc interventions. The reform agenda strategically included both technical and social/behavioural contents, with legislative changes, establishment of necessary institutions, new technology, capacity building, citizen engagement, and behaviour change communication. Continued engagement over 17 years has led to sustainable rooted reforms. Today, procurement practitioners from other countries in South Asia and other regions visit Bangladesh to learn about systematic changes in public procurement.

Winds of change

Institutional mechanism: The government established a nodal agency, Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU) within the Implementation Monitoring and Evaluation Division (IMED) of the Ministry of Planning in 2002. The CPTU was fully funded by the government and was positioned within the government’s existing framework. Over time, the CPTU’s visibility grew, as did its credibility among public procuring agencies and bidding community.

Legislative framework: In 2003, the government initially introduced Public Procurement Regulations, followed by a Public Procurement Act in 2006, with necessary rules in 2008.

Commitment and ownership: A bottom-up approach helped instill commitment in all level of bureaucracy. Initially, mostly the junior-mid-level public officials of four key public sector agencies and a young tenderers’ community owned the changes. In the first few years, the focus was on legislation and some capacity building efforts. This had limited success until 2007 when the government adopted a holistic approach. It was complimented by a behaviour change communication programme, followed by piloting of a digital technology (electronic government procurement, or e-GP) in 2011. The e-GP grew in popularity as it reduced rampant bid-rigging, coercion and collusion. Seeing this, the political leaders became interested. The Honorable Prime Minister supported and mandated the e-GP’s rollout across the country.

Digital technology: With the World Bank’s support, the government rolled outthe e-GP portal in 2011, making the entire tendering process, from tender invitation to contract award, online. Today more than half of the national budget spent on procurement is processed through the e-GP. By 2020, the government expects all public sector agencies to use the system. The e-GP has its own source of revenue from fees of registration, renewal, and sale of tender documents which made the system self-sustainable.

The e-GP’s exponential growth since its starting in 2012 is demonstrated by the increase in: the number of registered tenderers by 200-fold (from 294 to about 60,000); the number of online tender invitations by over 20,000 times (from 14 to over 290,000); and the value of tender invitations by 1200-fold (from $3 million to $37 billion).

Capacity building and professionalisation: TheCPTU facilitated a collaboration between international and local training institutes to create a pool of well-trained procurement professionals in the country. It designed a capacity development model with two distinct parts: procurement practitioner training and stakeholder sensitisation. The government is further professionalising procurement with accreditation at four tiers-based on experience and qualification. More than 37,000 people (national trainers, procurement practitioners, bidders, civil servants, banks, auditors, anti-corruption/ judiciary officials, and journalists) received training.

Communication and citizen engagement: To demystify procurement and raise citizen awareness, an extensive behaviour change communication campaign was rolled out. The campaign targeted different strata of communities, including political leaders, implementers, bidders, bankers, civil societies, academia, journalists and common citizens.

In order to encourage dialogue and accountability and to enable citizens to participate in the procurement cycle, four platforms were formed: (1) Public Private Stakeholders Committee: A high-level national committee to oversee policy guidance and debate; (2) Government Tenderers’ Forum: District level forums for informal dialogue between public procurement entities and tendering community; (3) Site-Specific Citizen Monitoring Groups: groups made up of trained local representatives to monitor implementation of contracts at the local level; (4) Citizens’ Portal (to be launched in 2019): A portal where public procurement data, both from the supply and demand side of governance, is available to procuring entities and citizens.

Results of Reform

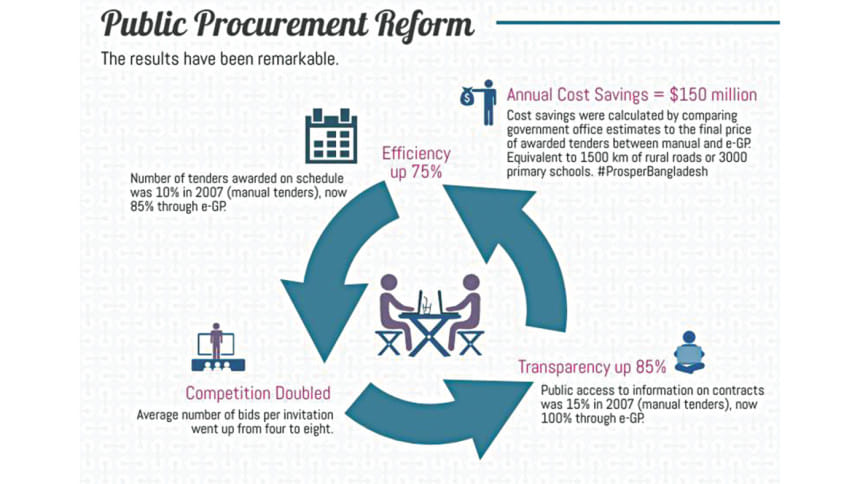

These changes improved the delivery of public services with annual savings of about $150 million from four key agencies only – enough money to build more than 1,500 kilometres of rural roads or 3,000 primary schools in Bangladesh. Furthermore, efficiency, transparency and competition increased, and we see a visible decrease of newspaper reports on bid-rigging and procurement-related violence.

Challenges and enabling conditions for a sustainable reform

Enabling conditions for a sustainable reform are not straightforward, and often follow a complex trajectory, affected by external influence, political economy, conflicting interest of stakeholders, corrupt practices, and reluctance to change. Though procurement landscape is reshaped over the years with substantial progress, yet challenges remain, particularly in maintaining consistency in the legal structure, limited delegation of financial powers, inadequate systemic in-built monitoring mechanism, appropriate framework for professionalisation, and contract management.

In this journey, a crucial enabler was the understanding of the country’s operating context with the government as the driver of reforms, and contribution from political leaders, reform-minded officials, bidding community, and civil society.

Zafrul Islam is the lead procurement specialist and Mercy Tembon is the country director for Bangladesh and Bhutan, World Bank.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments