How democracy backslides

We are living in a time which can no longer be described as a democratic era. Almost 61 percent of the global population now live under systems which are either 'not free' or 'partly free' according to Freedom House, a Washington-based organisation which tracks the state of democracy around the world. The Freedom of the World Report 2019, published early this year, documented that only 39 percent of the global population are living under systems which can be described as 'free.' These designations are based on the extent and quality of civil and political rights enjoyed by citizens. Similar figures have been presented by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). Based on a four-fold typology of existing systems of governance—full democracies, flawed democracies, hybrid regimes and authoritarian regimes—the EIU account shows 47.7 percent of the global population were in countries in full and flawed democracies in 2018. Of the remainder, almost 36 percent are in authoritarian systems.

This state of democracy hasn't emerged in a year; there was no single spectacular event which can be marked as the turning point, instead this has developed over a period of more than a decade and a half. The world has witnessed the gradual, at times precipitous, decline of democracy during this period. Country after country, in various continents, has capitulated to the authoritarian temptation. The reversal of the gains made since 1974 began in the early 2000s but became a clear pattern and went into a downward spiral since 2005. Since then, the number of democratic countries has decreased significantly, and consequently the number of undemocratic states has risen. Equally important is the emergence of countries which stand between the two extremes—described by Freedom House as 'Partly Free' and the EIU as 'hybrid regimes'—regimes which combine both democratic and authoritarian traits, for example, frequent and direct elections, and high levels of political repression and exclusion. The number of these in 2018 were 29, with 16.7 percent of the global population.

The process of this reversal of the spread of democracy, also described as democratic backsliding or democratic erosion or de-democratisation, has reached its consecutive 13th year in 2018. It is not surprising that the wave of democratisation has experienced backsliding. It has happened before. Samuel Huntington's Wave Theories showed that after the first long wave between 1828 and 1926, there was a a reverse wave which lasted for 20 years (1922-1942); the second wave of democratisation (1943-1962) was followed by the second reverse wave of 17 years (1958-1975). The much cherished and celebrated third wave began in 1975 and continued at least until the early 2000s. But, by 2005, signs became palpable that the situation has changed.

There are some distinct features of this round of backsliding—the third reverse wave. Firstly, the process has affected the countries which were the most vulnerable—the countries which began the journey towards democratisation after 1988. According to Freedom House, "of the 23 countries that suffered a negative status change over the past 13 years (moving from Free to Partly Free, or Partly Free to Not Free), almost two-thirds (61 percent) had earned a positive status change after 1988." The interruption of transition, either as stagnation or outright reversal, has happened in at least 32 instances between 2000 and 2014, according to available data and analyses. Except for the time of the beginning of the democratisation process, there is very little common to these countries located in various continents and at various stages of development. Secondly, the 'consolidated democracies', countries with a long history of democracy which were expected to have capabilities to endure, are witnessing democratic erosion, if not breakdown. The rise of Donald Trump in the United States epitomised this aspect while many of the European countries are experiencing this phenomenon. Thirdly, there are ample signs that citizens of various countries, for disparate reasons, have expressed dissatisfaction about the way democracy has been practiced. Widespread perception, in many instances backed up with enough information, is that democracy has become beholden to a small group of people in respective countries. Fourthly, the efforts to undermine democracy has global backers, such as Russia and China, who not only want to challenge the liberal democratic ideology and system, but also actively pursue the goal with deep pockets. Fifthly, unlike previous waves of backsliding, a new form of undemocratic system—which appears to be democratic but essentially authoritarian – have proliferated, making it difficult to separate them from democratic states.

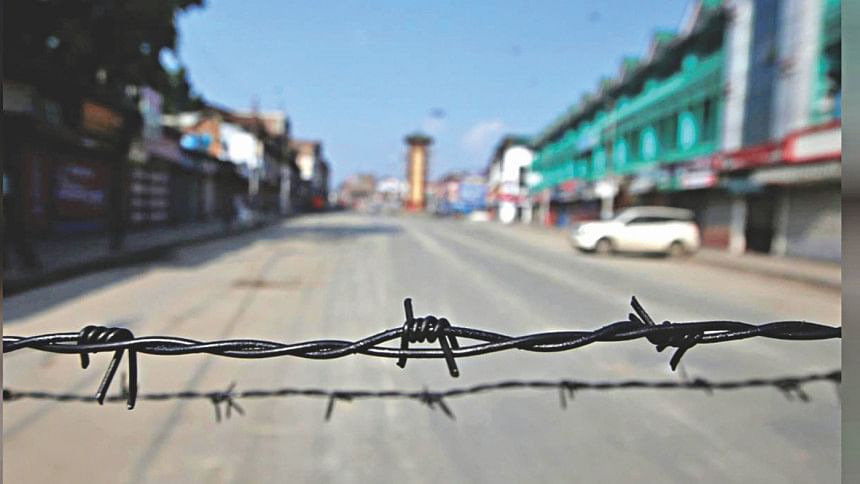

The consequences of the democratic backsliding have been discussed at length by scholars, analysts and journalists. As I have previously noted, in the event of the retreat of democracy, "citizens' fundamental rights are severely curtailed, space for dissent shrinks, institutional protection to opponents of the government disappear, freedom of expressions and assembly become limited at best, media are 'bought off or bullied into self-censorship', legislative bodies become weak and ineffective, the judiciary becomes subordinate to the executive, patriotism of the opposition is questioned and above all, a demagogue ascends to the helm of power with the promise of applying simplistic solutions to all the complex problems by himself/herself. These, in various degrees, become the defining features of a polity and normalised with dubious justifications" ("Democracy in Crisis: What we know and what we don't", The Daily Star, September 15, 2018).

The democratic backsliding, although a global phenomenon, takes place within a country and over a period of time. How does that process unfold? Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt's groundbreaking book, How Democracies Die, offers a model of the process. They have argued that there are three stages of democratic backsliding; these stages are—Stage 1: Target the "referees"; Stage 2: Target opponents of the government; Stage 3: Change the "rules of the game".

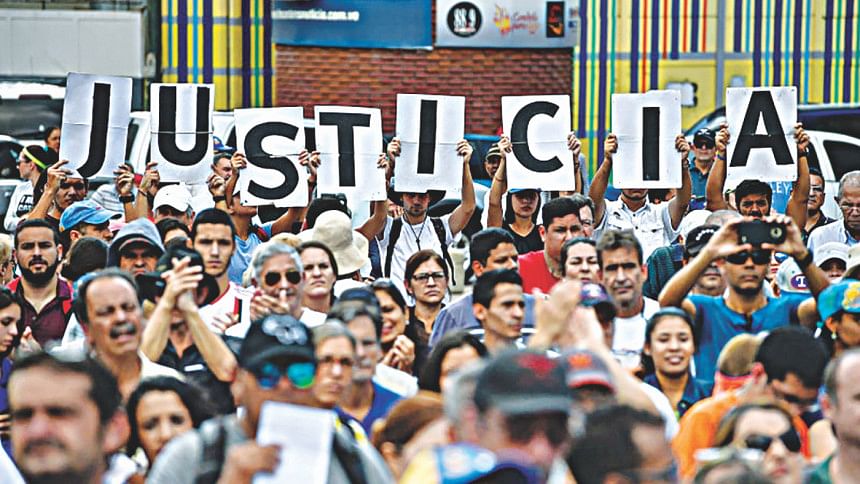

Drawing on their model and based on the experiences of various countries we can identify the details each stage entails. In the first stage, anti-democratic forces target the institutions which are essential to protecting the neutrality of the state and the rights of citizens. This is done with the objective of gaining control of law enforcement institutions, including the judiciary, law enforcement, tax and regulatory agencies. The ruling party, particularly its leader, intends to ensure the unconditional loyalty of these institutions. Various countries, which have experienced the erosion of democratic practices, for example Russia, Turkey, Venezuela, Cambodia, have undergone this phase with significant rapidity. By establishing complete control over these institutions, not only does the incumbent make these institutions ineffective but also makes these weapons against the opposition; these institutions become instruments for providing impunity to the extrajudicial activities of ruling party activists and state institutions. The damning effect of this action is the removal of any semblance of accountability.

The second stage—silencing the opponents and critics, that is the silencing opposition parties, media and civil society organisations—ensues either concurrently with the first stage or immediately after the first stage has reached a level of comfort with the incumbent. It is in this context we can remember Freedom House's description of what has happened in the past 13 years—"More authoritarian powers are now banning opposition groups or jailing their leaders, dispensing with term limits, and tightening the screws on any independent media that remain." It is important to note that these new authoritarian rulers usually neither outrightly proscribe the major opposition nor do they eliminate them. Instead, opposition parties are weakened to the extent that they are suffocated. Many scholars have described this as 'strategic silencing'. Ensuring the subservience of the media has been an important aspect of the process. Freedom House has noted that beyond the electoral process, the most significant impact of the democratic backsliding has been on freedom of expression. Either they are domesticated or they are coerced into compliance. Restrictive laws are legislated and used in this stage to create a fear among journalists. With the emergence of social media, restrictions on print or electronic media are no longer enough to control the message. That is why we have witnessed the phenomenon called 'digital authoritarianism'. The Varieties of Democracy Project, known as VDem, based at Gothenburg University of Sweden, in its annual report of 2019, have identified this as one of the three major challenges to democracy.

The third stage of the de-democratisation is establishing complete control of the ruling party. This is achieved through changes in the constitution and legislative bodies. It is in this stage that electoral systems are shaped in such a manner that it delivers victory to the incumbent, even without any apparent electoral fraud. While Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt have underscored the institutional aspect of establishing dominance, there is another aspect which is equally important—establishing control over the discursive arena.

In the past decade and a half, we have witnessed the unfolding of these stages—often in this order, but occasionally in a different order suitable to the specific country. In whatever order have they unfolded, the objectives have remained the same: to create a system of governance with democratic pretense but with no democratic substance.

On previous occasions, despite adverse situation and some innate weaknesses, democracy has bounced back. It has demonstrated resilience, time and again.

Ali Riaz is a distinguished professor of political science at Illinois State University, USA. His recent publication is titled Voting in a Hybrid Regime: Explaining the 2018 Bangladeshi Election (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments