Managing Bangladesh’s external account imbalance

Bangladesh has recorded an unprecedented 8.3 percent economic growth in the 2019 fiscal year. An accelerating economic growth coupled with a declining population growth led its per capita GDP to grow from USD 576 to about USD 2,000 in the last decade alone. The country is poised to become a developing country by 2024, but there are a few challenges that are threatening its macroeconomic stability. An unsustainable external account imbalance is one of them.

At present, the money market in Bangladesh is plagued with a worsening liquidity crisis. The liquidity crisis is surely an outcome of the ballooning current account deficits of recent times. This surge in current account imbalance is an outcome of rising dissaving by both the government and the private sector. Government dissaving is primarily driven by the government's commitment to spending more for building big infrastructures. The government is investing tens of billions of dollars on mega projects. Against the soaring spending, the government revenue as measured by tax-GDP ratio has remained stagnated in the last decade. Public dissaving, thus, increased in recent times.

The private sector also incurred rising dissaving in recent times. In the two years since 2017, the private sector seemingly borrowed and invested heavily but gross private saving did not rise in a commensurate way. The biggest problem in the surging volume of private-sector investment is the quality of the investment. Private-sector investment in Bangladesh is heavily bank-centric. So there has been massive borrowing from banks and financial institutions in order to finance big projects, particularly in energy and other infrastructures. In an environment of weak regulations and lack of enforceability, bad borrowers found it very easy to redirect a part of their borrowings towards unauthorised ends.

The rising current account deficits happened as a result of both private and public sector dissavings. Bangladesh did not have significant current account imbalances until FY2016. But since then, current account deficits worsened, amounting to about USD 8.8 billion in FY2017-18. The situation has improved to some extent recently, although deficits have remained large. It is estimated to be USD 5.3 billion in FY2018-19, and predicted to be USD 4.6 billion in FY2019-20.

Now, in macroeconomics, a rising current account deficit is always accompanied by real exchange rate appreciation and that exactly happened in Bangladesh. Real exchange rate is the ratio between home price and foreign price converted in terms of home currency. Given that foreign price (e.g. price level in the US and Europe) is changing at a very slow rate, to the tune of about 1-2 percent per year, the domestic price level in Bangladesh has increased by 7-11 percent per year over the last decade. This implies that Bangladesh had a persistent home inflation differential against its major trading partners. When nominal exchange rate is de facto fixed within a band and the domestic price level is rising faster than foreign price level, the home country experiences a persistent real exchange rate appreciation. This is exactly what happened in Bangladesh in the last decade. And that is at the heart of an unsustainable current account imbalance in the country.

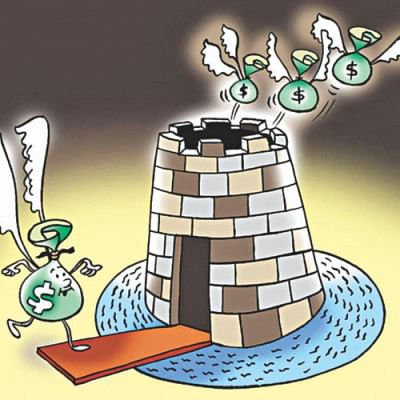

Money market is facing a crushing liquidity crisis because the central bank kept selling US dollars to commercial banks in order to finance the surging current account deficits amid a fixed Taka/Dollar exchange rate. When the central bank sells dollars to support its commitment to the nominal exchange rate, a depletion of actual and potential foreign exchange reserves happens. Money supply contracts as an outcome. Thus, the current episode of liquidity crisis arises from the surging current account deficits in recent years.

The flow of both inward remittances and exports registered a modest growth in 2018/19 fiscal year and that helped ease the growing tensions in the foreign exchange market. These are positive developments definitely. But we have to be cautious. Current account deficit remained at USD 5.3 billion in FY2018-19 and it is predicted to remain so in FY2019-20. Furthermore, this export growth may not sustain unless exports are made more competitive in the foreign market. Our exportable goods lost price competitiveness in foreign markets in the last 10 years because of a persistent real exchange rate appreciation. Our import growth in the last two years happened to be the fastest and that is causing the foreign exchange reserve to be stagnant at USD 32 billion in the last four years. Recently, a downward pressure is seen at the foreign exchange reserve level. So, the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves that happened after 2010 has now stopped. This is posing a danger to macroeconomic stability.

Bangladesh Bank has continued to inject US dollars in the banking sector to stabilise the volatility in the foreign exchange market. The selling of US dollars by the central bank for meeting the rising foreign exchange demand in the market is an indication of disequilibrium in the foreign exchange market. This strategy is inappropriate because it will further deplete the foreign exchange reserve—a barometer of macroeconomic stability. The central bank's intervention further implies that Taka is overvalued against the US dollar. A persistent current account deficit is at the heart of this rising demand for foreign exchange. The most viable strategy to address this disequilibrium is to depreciate Taka against the US dollar. That will discourage imports and increase price competitiveness of exports. Non-Resident Bangladeshis (NRBs) will also find the devaluation an incentive for their remittances. The inflow of remittances will rise substantially as a result of devaluation. Devaluation is the only way to stabilise foreign exchange and money market disequilibrium.

That said, the decision of Bangladesh Bank to grant 2 percent cash incentives to Non-Resident Bangladeshis is a bad public policy. The central bank admitted that the flow of inward remittances needed to be compensated "for an overvalued exchange rate of Taka against foreign currencies." Bangladesh Bank is taking this desperate move to attract an increasing flow of inward remittances. As the current account deficit is large and persistent, foreign exchange reserve is depleting fast. The fundamental question is if the nominal exchange rate is overvalued, which it is, why does the central bank choose a selective cash incentive only for foreign remittances? This will create many distortions in the economy.

I think Bangladesh Bank should first recognise that the Taka is overvalued. Then it must go for a gradual devaluation of Taka. That will produce a wide array of benefits. It will stimulate NRBs to send home more foreign exchanges. It will increase price competitiveness of exports and discourage imports of all kinds. And we must reduce double-digit growth in imports. We must decrease government spending in unproductive areas. We must reign in unsustainable public dissaving. A Taka devaluation will surely cause the current account imbalance to improve in the long term, slow down foreign exchange reserve depletion, ease the liquidity crisis in the banking system, and bring about macroeconomic growth and stability.

The policymakers' fear that a Taka devaluation will cause hyperinflation is unwarranted. A Taka devaluation will of course increase Taka price of imports. But the pass-through of an exchange rate devaluation to domestic prices is not uniform across products. So, the price effects are not one-to-one. Taka devaluation will also increase the Taka value of Bangladesh's external indebtedness. But we must not underestimate the long-term gains for exports and inward remittances. An overvalued exchange rate would cause external indebtedness to rise exponentially via depressing exports and other capital flows. There are many empirical studies that showed that the long-run effect of an exchange rate devaluation is always welfare-enhancing. It contributes towards external account adjustments and brings about macroeconomic stability.

Dr Mizanur Rahman is a professor of Department of Accounting & Information Systems at the University of Dhaka. He is an EducationUSA Fellow.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments