What’s stopping students with disabilities from pursuing education?

Many of us are probably not aware of the condition known in medical science as cerebral palsy, which affects a child's muscle tone, movement, and motor skills. It hinders the body's ability to move in a coordinated way and can affect other functions that involve motor skills and muscles. It is one of the 12 types of disabilities that were identified in the Persons with Disabilities Rights and Protection Act, 2013.

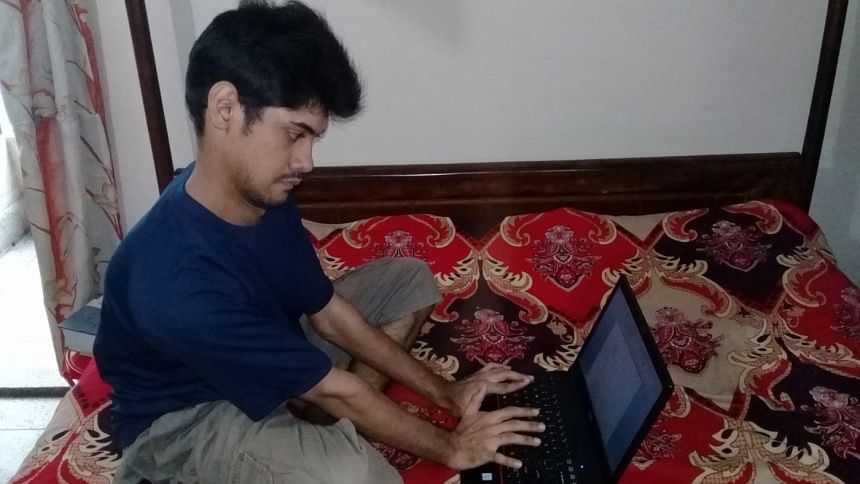

In February this year, 17-year-old AFM Mostofa Masud Priyo, who has this condition, sat for his SSC exams from Mohammadpur Government High School, and performed well in all subjects except for mathematics and "Bangladesh and Global Studies". He got 32 marks out of 100 in mathematics, and only 23 in Bangladesh and Global Studies. After his results were published, his father Mostafizur Rahman, a Supreme Court lawyer, filed a writ petition seeking reassessment of his son's answer scripts because, according to him, those were not assessed following any guidelines.

And on August 22, the High Court gave its verdict directing the authorities concerned to reassess Priyo's answer scripts with due care and publish his results within one month. The court also directed the government to formulate specific rules for assessment of answer scripts of students with disabilities in all public examinations.

While the Persons with Disabilities Rights and Protection Act, 2013 covers many aspects of the educational needs of students with disabilities, unfortunately, it does not give any direction whatsoever as to how such students' answer scripts in exams—including the public examinations—should be assessed. Which is why this HC verdict is so important.

It is beyond our understanding what parents of these children go through when they enrol in mainstream schools and colleges. There exist many social and structural barriers which hamper their education. While talking to Mostafizur Rahman recently, I came to know about a father's constant struggle to have his child educated in a mainstream educational institution.

While the law formulated in 2013 states clearly that there should be proper educational materials and effective teaching methods for students with disabilities in schools, colleges, and universities, in reality, there remains a big gap between what is written in the law and what the realities are on the ground. The methods used for the participation of these students in exams have not been designed as per the law. Therefore, when it comes to sitting for public exams, students with disabilities still face many difficulties, including in getting extra time or getting approval for a writing assistant. Needless to say, students with special needs should be given more time in exams compared to the regular students. The present provision of allocating 30 minutes' extra time is much less than what is needed.

When these students somehow manage to participate in the public exams, without much support from the authorities, they still face uncertainties because of the way their answer scripts are checked. Without specific rules and guidelines for assessing their scripts, many of them experience an abrupt end to their journey towards higher education.

The absence of such rules is precisely why Priyo had to face uncertainties in getting his results right. In the subject Bangladesh and Global Studies, Priyo answered all the 18 questions, but were only given marks for eight of the answers. "Maybe the examiner did not give him marks in the remaining answers because he could not understand his handwriting," said Mostafizur Rahman, Priyo's father. "It is a fact that those with cerebral palsy cannot write very clearly because they do not have much control over their hands." Priyo also could not take help of a writing assistant because of his speech problems.

So, there should be a mechanism to identify the answer scripts of students with disabilities so that the examiners can check those with special attention. When the candidates of public exams register their names with the education boards, the respective school and college authorities can point out in the registration forms the specific conditions of these students. According to Mostafizur Rahman, the education ministry should also consider appointing special examiners who will check their answer scripts according to the type of their disability.

Besides, for students with disabilities, particularly those with visual disabilities, it is still a big challenge to study science because of the lack of proper educational materials and trained teachers. Conversely, our neighbouring country, India, is far ahead of us in terms of fulfilling the needs of the students who want to study science.

Rifat Pasha, who completed his Master's in International Relations from Dhaka University, said that he was not allowed to study economics because of his visual disability. While studying at the university, he also had to face a shortage of reading materials in braille. Although visually impaired students can take writing assistants in public exams, or use braille, there are not many examiners who understand braille. Currently working in an NGO, Rifat believes that there should be separate question papers in the SSC, HSC and other public exams for those with special needs.

As mentioned before, the Persons with Disabilities Rights and Protection Act, 2013 identifies 12 types of disabilities: physical disability, autism spectrum disorder, visual disability, intellectual disability, hearing disability, speech disability, multiple disability, cerebral palsy, down syndrome, deaf-blindness, mental illness leading to disability, etc. The Act was formulated to ensure equitable development for all. If this commitment has to be materialised, the particular needs of all these types of people have to be addressed. Around 3.2 million young people in Bangladesh have some form of disability. Facilities conducive to their needs should be created at all levels of mainstream education so that they can study and pursue their dreams without hindrance.

As I write this column, Priyo and his father are still waiting for the reassessment of his answer scripts, which should not take more than a month. There are many more students like Priyo whose fate hangs in the balance in the absence of a proper policy and a lack of enforcement of the existing legislation.

Naznin Tithi is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments