Of war criminals and hypocrites

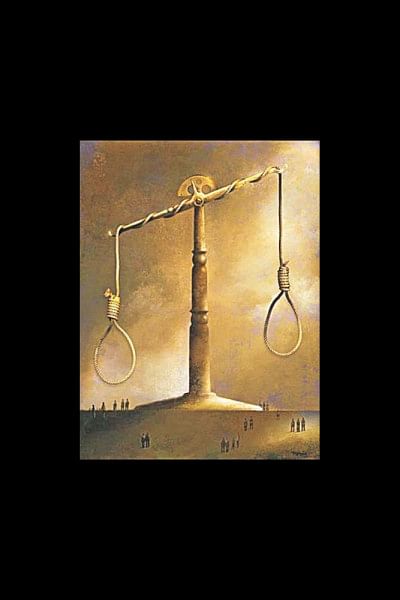

MUCH has happened over the last week including: 1) the executions of SQ Chowdhury and Mujahid and 2) the UN's call for abolishing the death penalty in Bangladesh. A few thoughts:

One.

I agree with the United Nations. The death penalty is inhuman and inhumane. What I don't understand, however, is how the UN can call for its abolition in Bangladesh while it [the death penalty]thrives around the world – from neighboring India to the land of the free (the United States). If we are to invoke stories of inhumanity, let us think about Glenn Ford, an African American man in Louisiana who spent 30 years in death row for a murder he didn't commit. Let us recall how Yakub Memon was put to death without reasonable evidence for "terrorism" only because his brother was Mushtaq "Tiger" Memon, a wanted criminal.

Two.

When I read that SQ Chowdhury didn't want to get up on the scaffold, I could distinguish between a human being and a demonised war criminal. In some ways, I could empathise with the fear that he must have felt, as he was hanged, his head covered . This, knowing, that he was at the helm of a spate of terrorism against minorities in 1971; knowing, that his house was a terror cell. Knowing that he took my grandfather, Lutfe Ahmed Chowdhury, to have him killed (and saved by Nabi Chowdhury, who under the guise of a Peace Committee member, helped many Bengalis in Chittagong).

Three.

As I see the various condemnations of the two executions from countries like Turkey and Pakistan, I can't help but wonder why they never stood up for the young Muslim man, Dzhokar Tsarnaev, who was, according to his lawyers, compelled to help his brother carry out a bomb attack in which several people died during the Boston Marathon, and according to analysts was a convenient scapegoat (details here: http://www.globalresearch.ca/fbi-evidence-proves-innocence-of-accused-boston-marathon-bomber-dzhokhar-tsarnaev/5469773). What happened to Muslim brotherhood in that situation? Why did the justice-hungry Muslim leaders of these two great nations shy away from the plight of a young man caught in the worst web of seemingly extremist values and Islamophobic propaganda?

Four.

Speaking of Dzhokar, if I was on the jury panel of Dzhokar Tsarnaev, I am not sure what I would have said to the other jurists, but I would not have condemned this man to death – even if I believed he was guilty. One court reporter said that Dzhokar's poise may have cost him his life; he stared at the table or ahead of him as witnesses recounted their anguish and pain on the day of the bombing for which he and his brother was found responsible. His lawyers painted the picture of a young man in the shadow of an older brother.

Dzhokar, on the other hand, had no verbal or non-verbal response. He simply sat there. Many in the media called him "evil" and the crimes "mindless." What tore at people was the lack of empathy, perhaps. Because there was no "rationale" that they could buy into. But can his lack of empathy justify the lack of empathy shown towards him?

Five.

I personally find celebrations of death rather distasteful. The celebrations in Boston and Dhaka left me befuddled because I tend to think that most people understand that human beings consist of a complex web of traits and states that inform their actions. But clearly they don't, so here's a spiel: While traits are genetically determined, states can change, which means people are not static. They are capable of great change, but only when they are given the opportunity to do so, when they take the opportunity to change their states. In pedagogical terms, it's like encouraging students by focusing on their strengths rather than beating them down by focusing only on the things they struggle with. It's like students who take responsibility for their own learning, instead of waiting to be spoon-fed.

Point being (and I'm sorry if it sounds didactic): let us learn to give people a second chance. Let us give them a chance to repent. And if they don't, it's not on us. But if they do, we have helped a man redeem himself.

Six.

Palestinian poet, Fady Joudah, while speaking at a panel at the Dhaka Lit Fest, mentioned his experience in India where he received a lot of support re: Israeli oppression against Palestinians but no one mentioned oppression in Kashmir. Just like no one mentioned any form of oppression taking place in Bangladesh against minority groups, be it in the Chittagong Hill Tracts or against Hindu minorities across the nation. And there lies the answer to how "hypocrisy" is created: some prefer to pick and choose causes to support.

But, it is important to condemn all forms of oppression; picking and choosing creates a hierarchy that undermines the larger cause of fighting all systems that promote oppression and all the isms that plague the world today. Picking and choosing also speaks to camps we are in rather than standing up against oppression, undermining the 'causes' themselves.

The writer is Assistant Professor, School of Social Work, University at Buffalo

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments