Jhenaidah: A death a day

What is Jhenaidah known for?

Sadly, the answer that comes first is 'suicide'.

According to the latest data from the World Health Organisation (WHO), Bangladesh witnesses six incidents of suicide for every 100,000 people (as of 2016). However, according to data from the offices of the civil surgeon and police superintendent, the suicide rate is 22 for every 100,000 people in Jhenaidah district. WHO data also shows that an average of 28 people take their own lives across the country every day, while Jhenaidah alone marks an average of one death every day.

What are the reasons behind such an alarming rate of suicide in Jhenaidah?

According to statistics from the local authorities, a total of 1,820 people have committed suicide between 2014 to 2018 in Jhenaidah. The number of people attempting suicide in these years is 12,536.

Star Weekend spoke to 10 survivors and family members of people who committed suicide in the area in an attempt to understand this disturbing phenomenon. The responses from the survivors were eye-opening. Take the example of Parvin Akter, a housewife of Dhananjoypur village of Jhenaidah Sadar upazila, who attempted suicide thrice.

27 years back, 11-year-old Parvin was married off to an illiterate and unemployed landless man. Her in-laws all lived at her husband's maternal uncle's house. He would keep busy the whole day with cards and gambling, she says. Parvin's father's financial condition wasn't enough for them to provide a dowry to the groom, which is why Parvin's husband and her in-laws soon started torturing her. There wasn't a day that went by, she says, when her husband or in-laws didn't beat her. But since there was no option of going back to her poor parents, Parvin stayed.

"They didn't allow me to eat properly or buy me a sari, let alone give me any money. I had to do all the household work and work in the fields to please them. The next year, I gave birth to my first son. I can still remember that after finishing the household chores, I would work in people's houses, carrying my son, but that too, didn't save me from their severe beatings and verbal abuse. With no other way, I hung myself from the ceiling, but I was saved—luckily or unluckily, I don't know which to say," explains Parvin.

After giving birth to her second son, one day while she was in the bathroom, a small fire broke out, in which her youngest son received severe burns, eventually losing his right hand. His treatment at the hospital, understandably, required a great deal of money. "After that incident, I was called evil and their beatings increased. I had no wish to live in this world. I took it for granted that my life has no meaning. There is nobody to share my sadness; I could not show the scars on my body to anyone. It was then that I tried to commit suicide again, twice. I'm still struggling to find meaning in this life," she adds.

Parvin represents one of the many women who attempted to, or committed, suicide due to the physical, mental or economic abuse they suffer in their domestic life. According to data from the civil surgeon's office, a total of 1,086 women committed suicide in the six upazilas of Jhenaidah district between 2014 and 2018. Another 9,373 women attempted suicide in this four-year period.

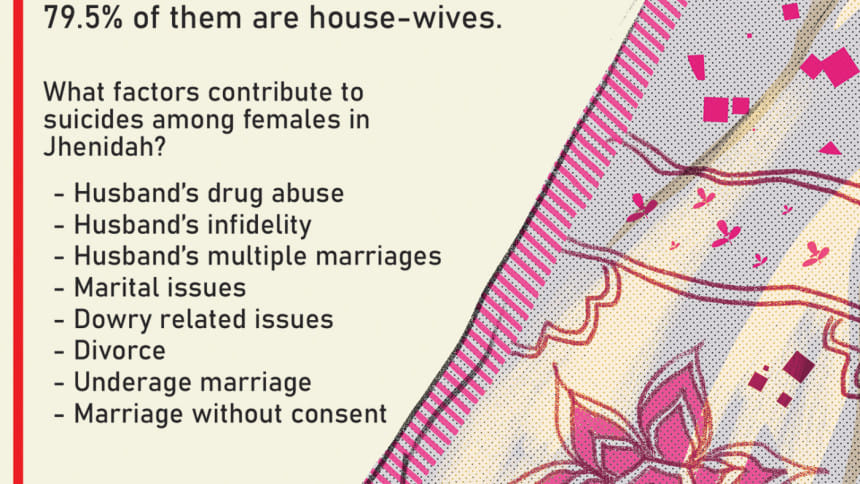

According to the local NGOs, human rights organisations, and the only suicide prevention NGO in Jhenaidah, Society for Voluntary Association (SOVA—the only NGO working for preventing suicide in Jhenaidah district), the main reasons behind these suicides is the violence and torture they endure as a result of polygamy, dowry, child marriage, drug addiction of their husbands, and domestic conflicts. According to BRAC's local office, they receive an average of 50 VAW-related complaints every month at their eight legal aid units in Jhenaidah.

Zahidul Islam, the CEO of SOVA, says that women are treated particularly badly here. "I hear many people saying that women commit suicide for silly reasons, such as her husband didn't buy her a sari or didn't bring sweetmeats from the market," he says. "They do not look for the deeper reasons. They never talk about the constant torture, deprivation, and disrespect women face for years. Rather, they talk about the triggers, and make a mockery of the whole thing," adds Islam.

Other survivors also echoed a similar experience. Aleya Begum, another woman living in the area, also attempted suicide thrice. Similar to Parvin, she was married to an illiterate, unemployed man at the age of seven. She gave birth to her two daughters by the age of 13, and her physical condition worsened and she became unable to walk. Her husband, who was now farming on another's land, did not take this well. Their poverty and now his wife's inability to 'please' him, in her words, led to violence in the household.

"I remember that every day was like hell. I was not in a physical condition to tolerate the severe beatings and abuse anymore. I took poison twice and tried to hang myself once," says Aleya.

30-year-old Shahina Akter has a similar story—an early marriage and poverty leading to domestic violence and eventually, her attempting suicide.

Star Weekend contacted Sharifa Khatun, director of local human rights NGO Welfare Efforts (WE) that has been working in the area since 1993. "From my viewpoint and experience, I have seen that only a few women in Jhenaidah town have the ability to choose a career and/or forge their own identity. But if we look at the grassroots villages of Jhenaidah, even today, women there have limited opportunities to go outside the home and earn money. Before getting married, girls are dependent on their parents and after marriage, on their husband or in-laws. The husbands usually don't allow them to leave the home without their permission. These women also lack the minimum ability to make a decision about family affairs. This is why, any kind of violence is inevitable in such family settings," she says.

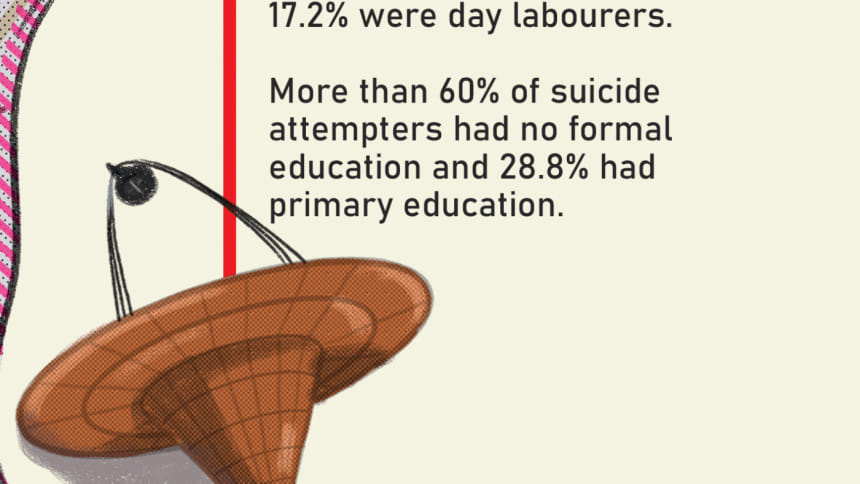

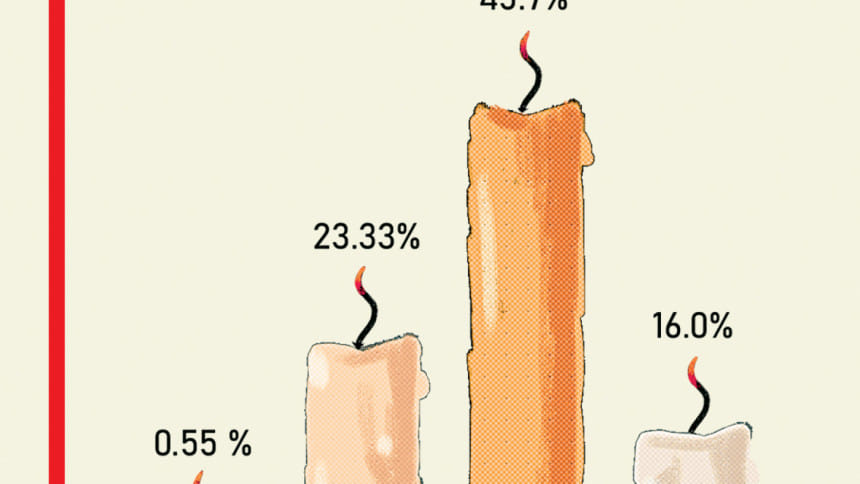

The only baseline survey in the area, conducted by SOVA in 2005, titled Surveillance and Reduction of Women's Suicidal Trends in Jhenidah: A Hot Spot with High Suicide Rate in Bangladesh, showed that around 80 percent women who committed and attempted suicide were housewives—44.7 percent of whom had no formal education, 15.8 percent had primary and 39.5 percent had secondary education.

The survey also showed that young people between the ages of 11 and 30 were more vulnerable to suicide. According to the Bangladesh national portal, the average life expectancy of the people in Jhenaidah district is 69 years.

Star Weekend also delved into the reasons for men in the district committing suicide. According to SOVA's volunteers, locals, and family members of the deceased, major reasons for their suicides are the men's failure to meet financial needs of the family, relationship troubles, extramarital relationships, and chronic illnesses. According to the survey, 43 percent of suicide attempts were by farmers. Islam, who conducted the survey, and his volunteers say that they found the main reason behind men's suicide to be family feuds due to financial problems.

For instance, Jesmin Akter says her husband Rezaul Islam hung himself when he was going through great losses in his wholesale business of selling paddy and jute. "My husband was a farmer all his life. But four years back, he saved some money to set up a business and in a short time span, ran up debts of Tk 300,000. Four months ago, he also had an accident which led to head injuries. Since then, he had been tense as people were coming to our house and asking for the money," she says.

"That morning, I went to drop my son at school, after finishing breakfast together. On coming home, I found him hanging from the ceiling. If he was given proper care and mental strength, I'm sure he wouldn't have done this. My mother-in-law [Jobeda Begum] died by taking poison 20 years ago, to escape a family conflict due to poor financial condition," says Jesmin.

Star Weekend spoke to Dr Anisur Rahman Khan, assistant professor at the department of sociology at East West University, who did his post-doctoral research on masculinity and suicide in Bangladesh. He chose to work in the district of Jhenaidah due to the high rate of suicide and did in-depth interviews with the family members of people who committed or attempted to commit suicide. Dr Rahman focused on the social factors linked with the suicide of men—financial instability was found to be the cause for several cases.

The income range of the families of the 20 male suicide subjects he worked on was between Tk 7,000 and Tk 20,000. "Since the men need to meet the socially prescribed responsibility of the sole breadwinner, this often instigates them to commit suicide when they fail to perfectly carry out the role. They try to escape, considering suicide to be the solution to their problems," says Dr Rahman.

Why do people in Jhenaidah commit suicide?

While suicide is not unusual in almost every district in Bangladesh, it is to yet to be discovered why Jhenaidah is a hotspot.

Local administration, and even the NGOs working there, seem to think that the people of Jhenaidah are very "emotional" and "not hardy". "The area is free from any kind of natural disasters—floods, river erosion, cyclones or tornadoes. People in this region have less capability to endure difficult conditions. They get emotional easily," says WE director Sharifa Khatun.

Analysing incidents of the people who died of, or attempted suicide, shows that a culture of acceptance has developed in the district, normalising the issue. Dr Rahman, who stayed in Jhenaidah for two months, says that if you walk 100 metres in the area, you will find a family where people have attempted or committed suicide. Although epidemiological studies demonstrate a significantly higher risk of suicidal behaviour among family members of suicide victims and attempters, suicide awareness and prevention campaigns have not taken off in the area.

"It is saddening that law enforcers even make mockery of death due to suicide. I heard once that a police officer was making fun of saying which upazila stood 'first' in suicide. This is so disappointing. It needs massive social change," says Islam. "In fact, hospitals don't have the proper resources to address the patients for treating the suicide attempters. The bodies are washed outside the hospitals in front of everyone."

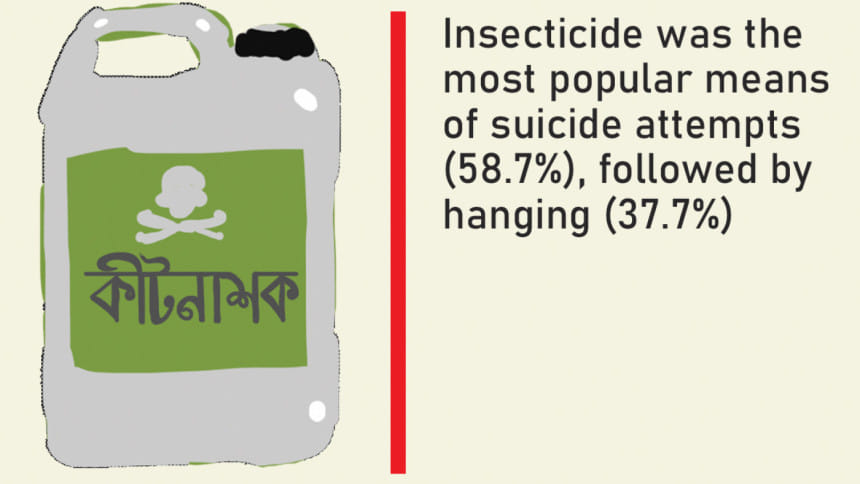

Besides, in an area where most families are involved in farming and agriculture, the easy availability and unsafe storage of insecticides is a major issue. Last year, a total of 1,794 people committed suicide by taking poison, while 2,284 attempted suicide.

Why does Jhenaidah get no attention?

Despite having the highest suicide rate in the country—22 per 100,000 —Jhenaidah does not have a proper preventive method to address the issue. The deputy commissioner and the district women's affairs officer acknowledge that they don't have adequate measures to address suicide. People don't have any mechanism to report a suicidal friend or family member, say the survivors and the family members of the deceased.

Despite the fact that there is a 2014 directive from the Prime Minister to establish an institution in Jhenaidah dedicated to studying suicides to find a way to resolve them, the project has yet to see the light of day. Also, the largest 100-bed Jhenaidah Sadar hospital has no post for a psychologist, let alone the upazila health complexes. There are a few private hospitals that have some guest doctors, but those remain inaccessible to those most prone to suicides.

According to the deputy commissioner Saroj Kumar Nath, the government is aware of the high suicide rate. "In recent times, the rate has reduced due to different campaigns in schools and colleges. The SOVA is working on organising anti-suicidal programmes to aware people. Besides, the scope of jobs and work has also increased in the district," he says.

But these are not the responsibilities of NGOs alone. According to locals and several school teachers, the programmes the DC was talking about cannot be counted as significant enough to address such a critical issue. "Just talking about suicide in a programme cannot prevent suicide. The government is doing nothing to address the root causes," says A Rahman, a teacher at a government high school of Kaliganj upazila of Jhenaidah.

Islam believes that the people who are at risk need one-on-one counseling because they are less likely to open up in a group about why they want to commit suicide. "A helpline service will also not work there, as a large number of women don't possess mobile phones or internet connections, or are not allowed to use cell phones. There must be something sustainable that doesn't end after a project ends. And this is why the government has to come forward," he stresses.

"A death a day can never be normal."

Illustrations: Nahfia Jahan Monni

Infographic: Shaer Reaz

Comments