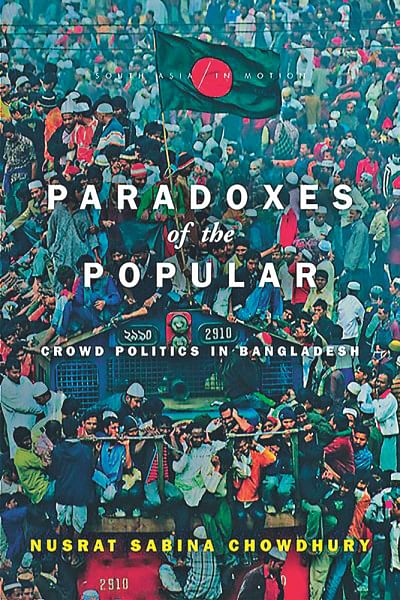

Paradoxes of the Popular: Crowd Politics in Bangladesh

The crowd fascinates and horrifies. The cheering populist rallies of European cities or the angry mobs meting out justice in our streets all signal the crowd as an enduring presence in global political life. It is also the main focus of my book, Paradoxes of the Popular: Crowd Politics in Bangladesh published by Stanford University Press in August 2019. I consider the crowd sociologically as well as conceptually, and come to the conclusion that it is both a solution and a scapegoat, that is, a true political enigma. The simultaneous vilification and validation of the crowd, or janata, in its Bangla iteration, is not new in the democratic culture of South Asia. It has also been the much-touted nemesis of the people and the public in scholarly treatises on democracy and public life. In the longer history of liberal political thought, the crowd is a permanent fixture against which the acts and utterances of the people are defined.

Crowds, michhil, and political gatherings have played formative roles in the origin story of Bangladesh. The crowd at Bangabondhu's speech at the Ramna Race Course in 1971 is a significant part of national folklore. The event of March 7 was a grand moment of declaration where the boundaries between popular demands for independence and constitutionalism were blurred to produce one of the most iconic moments – and sound bites – of East Pakistan's struggle for nationhood.

Mahmudul Huq's novel Jiban Amar Bon (Life is My Sister; 1972) starts a few days before Mujib's landmark speech. The war begins and ends within the novel, which is narrated in the third person. Jiban Amar Bon is largely about its central character Khoka's struggle to make sense of the events that were sweeping away the region and with it a whole generation. It is a tale of the main character coming face to face with what he likens to a force of nature. Khoka calls this unreflexive, uncouth, and hysterical entity by the name, janata.

To Khoka what was until then a skinny word wrapped in the wispy feathers of three letters, like dayita (beloved), jamini (night) or madira (wine), is suddenly spreading across the city in thunderous explosions – janata!

Janata is an active, affective and political configuration of manush, which is the word Khoka uses for "the people." The Sanskrit-derived gloss for the human can be either singular or plural. Manush howa is the process of growing up; it is a progression towards becoming a fully functioning, humane adult. It is at once developmental and social like in the expression, manush kora. But the word does not pack a political punch in the same way janata or janogon does. Manush speaks to an innate humanity that need not include political maturation or participation. Janata is a higher level of collectivity than the more passive manush or even bhir (crowdedness).

Even in the mythic, nationalist crowds of the early 1970s, Huq identifies a duality that haunts the figure of the crowd. It is this constitutive paradox that I explore by focusing on some of the more important mass political events of the past decade. From Phulbari to Shahbag, the protests that form the content and the background of Paradoxes of the Popular have been public in the sense that they took over public spaces for their articulation. They have been formally akin to the spontaneous assemblies that dotted parts of the world this past decade. Whether against corporate capital, land grabs, military rule, or war crimes trials, they have defied easy labeling, their form and content veering between progressive, patriotic, secular, religious, reformist, violent, radical and reactionary. My book attends to the minutiae of these protests by locating in the crowd the energy, agency and indeterminacy of mass politics.

***

I had spent much of 2007-2008 in Phulbari, about 180 miles from Dhaka, tracking down those who took part in one of the more successful crowd protests of recent years. Three young men were shot to death when the paramilitary, serving a multinational company's interest, tried to stop ordinary villagers from staging a gherao of the company's office. The violence, and the protests that had come before and after it, put Phulbari squarely on the map. It managed, for the first time, to bring a national energy crisis, a seemingly technocratic problem to be resolved behind closed doors, into public consciousness. Here, I had met Majeda, a rural woman, who was party to the burning of cash in an episode of spontaneous protest. In August 2006, she and a few other women from the neighborhood had come out of their homes to challenge the brutality of the border patrol guards that had led to the deaths the day before. Interviewed multiple times by journalists and activists who thronged Phulbari, she was by far the best-known representative of the "women" of Phulbari, a potent and eminently utilizable token of local resistance. Her profession as a sex worker was also widely known but rarely talked about. It was a public secret.

"I set Hussain's house on fire," Majeda blurted out, interrupting our conversation. "Then Hussain's house was put to fire. The sack of money burnt down. At last when there was a light wind, one could only see the seals on the notes." Addressing the older woman standing at the doorstep, she nearly shouted, "He kept money in the turmeric, Nani!" The reason behind her clear excitement in seeing the fire was not simply that money could be stored like condiment; money, when put to fire, also burnt in flames like any other object. Our conversation at the time of her interjection focused on the misdeeds of a particular "collaborator" whom I shall call Hussain. Locally known as a dalal, a collaborator was a ubiquitous figure in Phulbari, rife as it was with suspicions of profiting from the energy company, then called Asia Energy Corporation, and its insidious forms of corruption.

"How did you know that there was money there," I asked her. In response, Majeda repeated herself: "Because all the sacks burnt down! Only the seals were there. If you blew lightly on it, the sack would be all ashes." She went on to describe how the ashes were flying around in the wind, showing enough proof that the bills had indeed burnt down. What was offered as the ultimate evidence was the "seal" (for which she used the English word), the symbol of paper money's source of authority. For Majeda, this was visible even when the rest of the bill was consumed by fire.

Majeda's participation in crowd violence revealed the betrayal of a dalal, who had kept sacks full of money in his pantry. More important, the immolation of cash in protest elevated her and the money she had burnt, the latter deemed "dirty" because of its association with the energy company. She transformed and transcended her previously established role as a "public woman," although as a part of a pillaging crowd whose ability to reason was suspect. Caught in the midst of an emergent crisis of representation when allegations of collaboration were everywhere, through this collective act of plunder, Majeda created value as an individual as well as a member of a protesting crowd. Her use – or abuse – of paper money was a political act lodged in a system of meaning that tied productivity with morality. She remains a powerful icon of Phulbari's quest for justice.

The recuperation that had happened in Majeda's case was simultaneously denied to another person whose life was also tragically, and accidentally, tangled with the same events. Tarikul was a 20-year-old man from Phulbari who was one of the three people killed in 2006. He was a part of the michhil that was trying to get to the office of Asia Energy and eventually confronted the paramilitary. For Tarikul's mother, with whom I had the opportunity to speak, accident was the single operative theme. It dominated her version of how her son had become a victim of the events of August 26. Tarikul had no desire to join the procession. He was there only to see what was going on. In the midst of the chaos, his mobile phone fell out of his pocket. As he was about to pick it up, a paramilitary guard shot him. Had he not bent down to retrieve the phone, he would have been alive, his mother believed. A minor accident of a phone slipping out of his pocket eventuated in a fatal accident that was to become a critical event. The young man, as per his mother, was only accidentally a part of the crowd.

Like any accident, Tarikul's death was a culmination of missed cues and misrecognitions. When he bent down to pick up the phone, the border guards thought he was picking up a stone to hurl at them and reacted preemptively. Throwing stones or rocks at the police and other state agents was as common in this agitation as it has been elsewhere. It is a counter-hegemonic, violent, and potentially dangerous strategy that crowds employ when faced with an enemy of unequal force and might. Phulbari's Tarikul, however, was no average rioter. Devoid of any express political will, according to those who outlived him, he was a bystander who got caught up in the motions and was in a hurry to leave. The simple act of picking up a phone looked like he had a subversive motive. The accidental seemed intentional and in turn solicited violent intervention.

The crowds in Tunis, Tahrir Square, or Phulbari, for that matter, have made amply clear that martyrdom is ad hoc, improvised, uneven, contentious, and precarious. The line between death and martyrdom is rarely settled. It is impossible to know whether and how Tarikul's curiosity and attraction to spectacle would have set the stage for future politicization. Beyond his mother's lament of his untimely death and the ascription of martyrdom and retrospective inclusion of Tarikul in the core script of the movement, one can only speculate the possibilities that exist in such exposure to situational convergences that may, and indeed have, led to political awakening for other people in other places.

***

Looking past the spectacular to remain loyal to the intimate and the ordinary, my book privileges the imperceptible nature of politics. This is the politics that arises from the emergence of the miscounted – the vagabond, the wandering poor or the unruly peasant, for example. Attempts to harness and work with these imperceptible potentials are generally misrecognized and translated into familiar terms of representation, such as resistance or protest. The concept also has significance, I believe, for understanding political crowds. It is no coincidence that "mobility" refers to movement but also, the common people, the working classes, and the mob. Imperceptible politics are about dissent, but they are not always easily recognizable as resistance. They are comprised of everyday, singular, contingent acts which cannot be reduced to one procedural and necessary form of politics. These everyday cultural and practical exercises of claim-making, I argue, make up the politics of the crowd.

Situating the minutiae of crowd politics against this background, even when it defies a familiar script of resistance, is not the same as rehashing some "hoary revolutionary myth" about the crowd, as Jason Frank has recently suggested. This is not an attempt at finding in the crowd the direct expression of a unified and sacred popular voice but instead approaching it as a powerful, often self-contradictory, act of political representation. It is to ask when and how a group of individuals physically gathered in a public space can be understood to speak and act in the name of "the people." It is also, ultimately, to interrogate what animates the popular that evokes hope and despair about the fate of democracy itself, particularly the postcolonial version of which we experience in contemporary Bangladesh.

The crowd and not the coffee shop is where publicness is performed and communicated in Bangladesh as in many other places. Almost all postcolonial forms of politics rely heavily on the crowd to articulate claims to legitimacy. The protests featured in my book are, in effect, nodes in a long chain of negotiations, some more routine than others, between basic governance policies, state repression, and political violence that characterize a vast portion of the formerly colonized world. My book has captured many such moments in which the crowd has made its presence felt in assertions of democracy that may not look like so to those who stand behind more normative models of the concept, or seek them out in voting behavior surveys and nationalist histories.

While the glory of the crowd is inscribed in the memory of Bangladesh's political founding, the other, less dramatic, figure of the crowd resides in the everyday, political life of Bangladeshi citizens. My book explores these myriad dimensions and hopes to occasion a rethinking of the phenomenon of popular politics more broadly. The unfolding trajectory of Bangladesh's democracy, I argue, is best understood by historically and anthropologically locating the role and the ruse of the crowd— janata. Bangladesh's double postcoloniality bears on the present in a manner that is somewhat unique within the larger South Asian political landscape. The recent return of the crowd in the West has spurred scholarly and journalistic reflections on populism. Yet the crowd never left the postcolonial political scene. It is therefore my hope that the study of the fraught recent history of the crowd in Bangladesh in Paradoxes of the Popular will offer insights and resources to those interested in the global life of democracy.

Nusrat Sabina Chowdhury writes on popular sovereignty and political communication primarily through an anthropological lens. She's the author of Paradoxes of the Popular (Stanford University Press 2019), her first book, and a number of articles on the political culture of Bangladesh. Her current research interests are in old and new forms of surveillance and development infrastructure in Bangladesh and their co-emergence. She's an associate professor of anthropology at Amherst College in Massachusetts, USA.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments