Time and Space

Winter came early that year. Mid-October, a steady wind appeared and transformed Dhaka into a dust bowl; by November, a fog descended and obscured the moon.

Between noon and sunset, the sun beat down on the capital, but at dusk and dawn, the temperature dropped. Shawls took to the streets, dusty cars went home to sleep, roadside stalls awoke from slumber. Bhapas, cigarettes and chaa catered to an endless parade of incessant feet, conversations filled the air. With every shift of the wind, a new smell, at every block, a new adda. In open plots awaiting construction, badminton courts sprung up — fluorescent bulbs serenading entire colonies of bugs. Deep into the night, the sound of shuttlecocks lent rhythm to silence.

From where I stood on my balcony, other rooftops were visible — a few buildings away, two shadows were locked in embrace, in the distance, wedding lights were being set up. The few trees that had survived the onslaught of summer looked on in silence, the lower halves of their bodies peppered with posters — "Tuition Wanted," "For- Rent," "Broadband Internet first month free."

Dada had died in his sleep on a winter night like this one, nestled snugly between darkness and dawn. I was young, Nawra not much older. Bula had woken us up in the morning with the news that we needed to go to the hospital. Ammu and Baba were already there.

My first brush with death was poetic. The streets were empty, light starting to peek through the smog. In the distance by the traffic signal, a woman in a yellow vest was sweeping away the dirt. Nawra's shoes were white, shoelaces neatly tied. Mine were brown, clinging onto summer puddles; my shoelaces, however, were spotless.

Bula hadn't told us why we were going to the hospital, and as we walked, I found myself wondering why. I knew Dada was unwell, Ammu had told me so. I knew he had gone to see the doctor and the doctor had kept him back because he "needed to be monitored." I empathised with that — I was a monitor in class myself. Dada ate too many sweets. He needed to be kept in line.

But it didn't explain why we had to go, so I turned to Bula and asked her. "Is Dada okay?" She looked at me, eyes glassy with tears, and gripped my hand tightly in her's. "Ohee, Dada is no more."

"What does that mean, No More?"

No answer.

Perplexing.

When we got to the hospital, the half-moon windows of Suhrawardy welcomed us in. Sunlight swept in and splashed across the mosaic, but where there should have been joy, an unhappy air hung low and obfuscated everything. Everyone looked worried, like some collective Terrible Thing was about to happen. Ammu and Baba were waiting for us.

Baba had been crying. His shirt was wrinkled, hair disheveled, eyes bloodshot. Ammu hugged us, Baba followed. Knelt down and ruffled my hair. I hugged him back and got to the point.

"Baba, I want to see Dada." Nawra nodded in agreement.

Ammu and Baba looked at each other, then collectively looked at Bula. A silent consensus was reached, and we followed the adults up the stairs.

The room that Dada was in was crowded — nurses were milling about, family members lined the walls. Pushing past Boro Chacha, I found myself at the edge of the bed. A crisp white sheet covered most of Dada's body, but his face was uncovered. His eyes were closed, his gray hair freshly combed. There were cotton puffs in his nose. Lying motionless while life spun on around us, he looked unnaturally odd. Otherworldly. Beside me, Nawra had started to cry.

Words had never had weight until that moment. Suddenly, No More was a shortness of breath, a hot spring of tears. It was the turning back of time: sitting on Dada's lap at dinner, tasting the tobacco in his pipe when he wasn't looking, asking him for money when I wanted to buy candies. It was the smell of ator on Friday mornings and the freshness of new cotton on Eid. No More was everything I remembered, and everything I feared I had already forgotten congealed in an unimaginable mass in the pit of my stomach.

The room suddenly felt very cold. Turning back, I saw Baba's face buried in Ammu's hair. A Terrible Thing had happened.

That night, we all sat together with nothing to say. Nawra helped Ammu pack up Dada's clothes while I tried to cheer Baba up without success. When night deepened, we followed each other up the stairs to the roof.

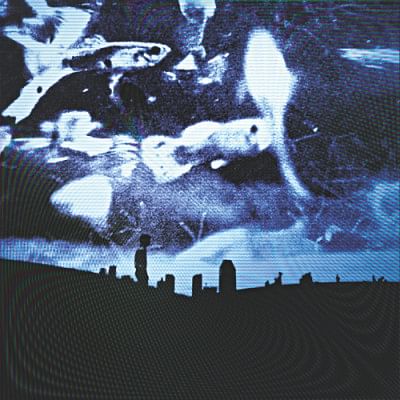

Above us, the fog was descending, ethereal in moonlight. Below us, badminton games were in full swing, bugs serenading light. And around us, unseen, time was turning and twisting itself into our lives, stealing everything worth anything.

Endlessly, mercilessly.

Imrul Islam works for the Bridge Initiative, a research project on Islamophobia in Washington DC.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments