Book publishing in tatters

Shahbagh, the intellectual heart of Dhaka, becomes a meeting place for renowned and promising authors, scholars, poets, journalists, readers, and intellectuals from far and wide, at least twice a year. Once during the Amar Ekushey Book fair in February and once during the Dhaka Lit Fest in November. The overflowing milieu of these festivals gives one the appearance that Bangladesh must be a haven for publishers and booksellers.

With such abundance of potential readers, it could have well been the reality. However, it is not. According to publishers, poor readership, excessive cost of production materials, absence of a distribution system, and negligence of the state to mitigate these problems have all pushed book publishing in Bangladesh to the edge of existence. Many renowned publishers can barely make their ends meet while younger publishers are struggling to keep their businesses alive.

Our publishing industry has a long and eventful past. According to Mohiuddin Ahmed, a veteran author, editor, and the founder of University Press Limited (UPL), the industry is closely linked with the emergence of Bengali nationalism in the late 1940s. In his book titled Bangladeshe Pustak Prokashona, Ahmed explains how pioneering publishers such as Nawroze Kitabistan, Ahmod Publishing House, and Maola Brothers began publishing creative literature that fuelled the movements in the 50s and 60s.

In 1954, the United Front (Jukta Front) achieved landslide victory in the elections to the then East Bengal Legislative Assembly with a pledge to recognise Bengali as one of the state languages of Pakistan. According to the promise, the Central Board for the Development of Bengali was established and under its patronisation renowned scholar Munir Chowdhury developed a Bengali keyboard called Munir Keyboard for the typewriter. It was a ground-breaking progress for the book publishing industry in Dhaka, especially for publishing Bengali books. Besides, the continuous politico-cultural movement against West Pakistani rulers in the late 50s and 60s gave birth to significant literary creations by the Bengali poets and authors, which also encouraged some of the notable publishing houses to emerge and flourish. Among them were Ahmod Publishing House (1954), Beauty Book House (1962), Khan Brothers (1966), Muktadhara etc.

The development of Bangladesh's publishing industry in the post-independence era is deeply indebted to the introduction of Amar Ekushey Book Fair. On February 8, 1972 the legendary publisher and founder of Muktadhara, Chittaranjan Saha arranged a simple exhibition of 32 books at the Bangla Academy premises, which he published from Kolkata under the banner of Shadhin Bangla Shahitto Porishod (Free Bengal Literary Council) during the nine months of the Liberation War. This historic initiative is considered as the first stepping stone of Amar Ekushey Book Fair, the event at the heart of the country's publishing cycle. Afterwards, publishers like Chittaranjan Saha, Mohiuddin Ahmedm and Ruhul Amin Nizami of Standard Publishers organised a book fair on their own initiative with their own productions, which was later taken over by Bangla Academy.

The dedication and hard work of these pioneering publishers, scholars, and book lovers have not come to fruition yet. Publishers have been demanding for decades for book publishing to be recognised as an industry. Despite repeated promises, the government has not taken any steps to materialise this demand. Arifur Rahman Nayeem, chief executive of Oitijjhya, a leading publishing house, says, "Government has patronised every sector of art and culture except the publishing sector. For the filmmakers, state has granted loan for up to five million taka on a very small interest. But there is no such provision for book publishers. If this sector can be recognised as an industry, publishers will get facilities such as import of paper at subsidised rates and loan on small interest for young entrepreneurs, and a book distribution channel will develop all over the country. To keep this sector alive, we really need to bring in meritorious young entrepreneurs in this sector and for doing so, the government should recognise it as an industry."

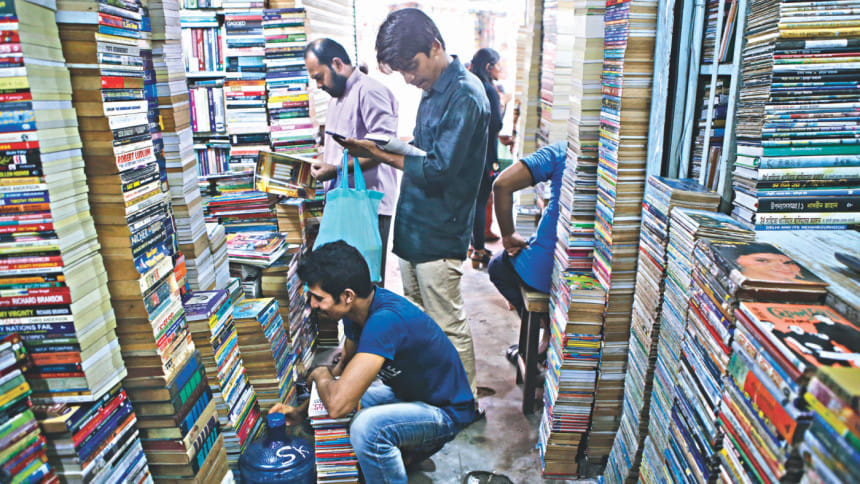

Lack of a distribution channel and cost of paper are some of the biggest challenges for book publishers. According to Nayeem, "More than 15 or 20 years ago, we used to sell books all over the country through sales representatives. However, due to the financial fall of this sector, we could not afford to pay them. Now, the publishing industry is centred in Dhaka and focused mostly on Amar Ekushey Book Fair. You will find a few bookstores in other cities and towns where fiction books are sold. Most book shops sell textbooks and guidebooks for examinees and job seekers. We supply books only to some interested book sellers outside Dhaka," says Nayeem.

Mahrukh Mohiuddin, managing director, UPL shares a similar experience. "As a publisher of academic and research-based books, we really struggle to promote our books in the market," she says. "Our primary challenge is severe dearth of skilled editors, proof readers, and reviewers who can work on academic manuscripts. We hardly get a few quality manuscripts every year due to lack of research projects. Due to these shortcomings, we are already under such immense pressure that we can just publish our books but still cannot afford to invest in developing a marketing strategy."

As a matter of fact, very few publishers in Bangladesh have adequate editing facilities. Scarcity of skilled book editors and lack of awareness in this subject among publishers are some of the significant reasons behind Bangladesh's weak publishing industry. Rakhal Raha, editor-in-chief of Shompadona, a manuscript editing and indexing house, has been training editors for six years. He shares his experience, "Unfortunately there is no sense of editing among most Bangladeshi publishers. To publish books, they solely depend on the writers' popularity and just print their manuscript after a bit of proof reading."

"In many countries, universities and institutions offer different levels of courses on publishing and editing. However, despite having such a huge market, there is no such facility in Bangladesh," he adds.

Mahrukh also points out the exorbitant price and poor quality of paper as one of the biggest challenges of publishers. "There is heavy import duty on imported papers. So, we have to purchase papers from Bangladeshi manufacturers who charge only a few takas less than the foreign manufacturers; but in terms of quality, Bangladeshi papers are awfully inferior to the imported ones. There is also a visible lack of paper market monitoring. We publishers are forced to buy their paper at whatever price they claim and of whatever quality they produce. Due to high price and poor paper quality, we are really struggling to produce quality publication."

In such a situation, how young and new publishers are surviving is a story of passion and bitter struggle. Arifur Rahman and his team of artists, writers, and editors founded Nokta, an emerging publishing house that publishes books mostly on visual arts since late 2012.

"We founded Nokta because we are passionate about spreading knowledge of arts, aesthetics, politics, and philosophy of images. Our theme requires that we publish our books only with high quality imported papers which means our production cost is very high. Unfortunately, in our country, readers in general have the tendency to think that a book's price is determined by the number of its pages. They don't think that quality of design, quality of content can also have its own value."

Due to poor readership and high cost of production, Arif is also struggling to run his business. "I don't know for how long I will be able to continue this publishing house. I cannot afford to maintain our own office. One of my acquaintances allowed me to use his space as our office but it was agreed that we would leave it as soon as we could afford to rent an office of our own. We were told to leave our previous address because we could not pay the rent regularly even though they offered us a discounted rent. But I want to continue this venture until a sizeable readership of art and aesthetics is created in our country," adds Arif.

Some publishers are hopeful that the spread of internet and the digital marketplace can solve a significant part of the problem. Nayeem argues, "At present, we have started to read a lot of content thanks to our devices. In this way, we have developed a habit of reading. Many people are becoming interested to read books by reading their reviews and advertisements on social media. In the online marketplaces, these readers can order the books they want and have it at their doorstep thanks to cash-on-delivery services of these marketplaces. This has simplified our task of distribution and marketing a lot. But I don't think the digital version of books will replace its tactile appeal. So expansion of the internet will not be a threat for the publishing industry; it will help us to expand in the future."

Mahrukh also believes that the reader base is growing with the expansion of internet facilities. She says, "We often arrange UPL book fairs in different institutions. We see interest among students who purchase our books a lot. Many of them learn about our books through online reviews and social media. If we can develop secured online platforms, we shall be able to create a more efficient book market."

However, to exploit these upcoming opportunities, book publishers in Bangladesh now want a friendly market where they can survive and thrive. Despite such a sorry state of affairs, it is reassuring to see that still we are organising festivals like Dhaka Lit Fest and Amar Ekushey Book Fair on even larger scales every year. Now is the time to think about qualitative development. We need to ensure excellence in book writing and publishing. And to do so, readership has to be developed in every part, in every institution of our society.

Md Shahnawaz Khan Chandan can be contacted at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments