Bangladesh’s untapped potential in export of ceramics

Ceramic tiles, tableware and sanitary ware have become an integral part of today’s life. It makes a world of a difference to the look and characteristics of a structure’s interiors and exteriors.

Though the use of ceramics dates back to a thousand years, its mass use began much later. It gained momentum in Bangladesh in recent years. The large number of shops selling porcelain products at retail points – at both district and thana levels – is evidence of its widespread use and demand.

Despite a slowdown in many other manufacturing sectors, the Bangladeshi ceramics industry has continued to grow at a double-digit rate for the past decade, mainly due to growing demand from local customers. Local consumption will continue to grow with the country’s healthy economic growth and urbanisation.

Export of ceramic products, which has remained stagnant at around USD 50 million for the past couple of years, may pick up in the years to come as the government has offered 10 percent cash incentive on export of the products in fiscal 2017-18. People in the sector predict that its export could reach as high as USD 1 billion by 2025.

Yet, this rosy picture could be dented due to some challenges the industry has been facing for the past two years.

Irfan Uddin, general secretary of the Bangladesh Ceramic Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BCMEA), said ceramics was a capital-intensive industry in which setting up of a factory required a minimum investment of Tk 100 crore.

“Rising interest rates – 12 to 14 percent – have been impeding the sector’s expansion. Lack of skilled manpower is another challenge in the path of the sector growing further,” said Irfan, also a director of FARR Ceramics.

“Middle Eastern countries are moving towards imposing an anti-dumping duty on Indian ceramics, which could open up a new avenue for export of Bangladeshi products,” he said.

“We need more factories and expansion of existing ones to grab the export market,” he pointed out.

Traditionally, Japan, the United Kingdom, Germany and other European countries have dominated the export market of ceramic products to world markets. But a jump in production costs, including wages and currency appreciation, made ceramic manufacturing unfeasible for many, even China.

Bangladesh’s first ceramic plant – Tajma Ceramic Industry – was established in Bogura in 1958. But it took over three decades to take the number of factories to double digits. Since the mid-90s entrepreneurs started investing in the sector. Now there are over 60 factories and over a dozen in the pipeline, according to the BCMEA. A third of the factories are tableware makers.

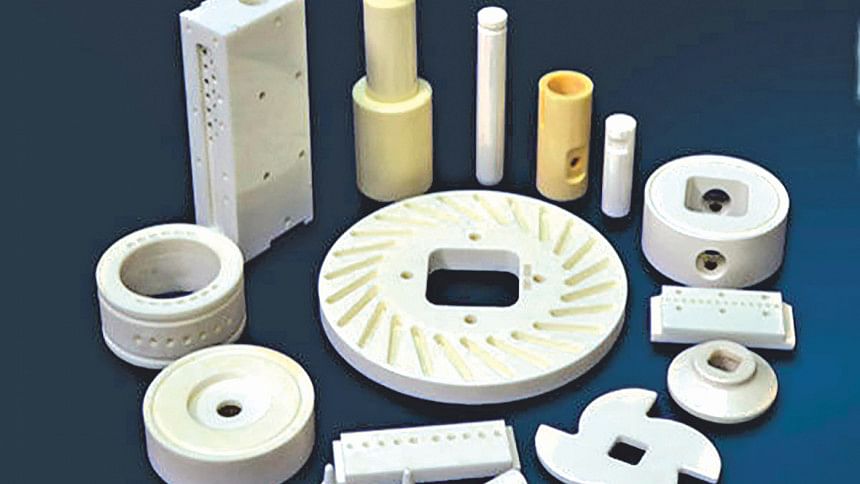

Now Bangladesh produces ceramics mainly in the form of tableware, sanitary ware and tiles. According to the BCMEA, the industry produced over 25 crore pieces of tableware, nearly 20 crore square metres of tiles and over 83 lakh pieces of sanitary ware in fiscal 2017-18. Bangladesh is almost self-sufficient in these products, a development opposite to the scenario in the 90s.

Initially, most of the factories were targeting export, but things have changed now with the steady rise in people’s purchasing power in Bangladesh, industry insiders said.

The BCMEA data showed that tiles and sanitary ware’s domestic demand is higher than that of the country’s production capacity. Total domestic demand for tiles is around 26 crore square metres against a production capacity of 20 crore square metres. Similarly, actual production of tiles is less than the demand.

The gap in demand and production is met by import as nearly 24 percent of demand for tiles is still import-dependent.

“We have a lot of scope to grow. It is a growing industry and can become a much bigger one in the next five years,” said Md Shirajul Islam Mollah, president of the BCMEA.

According to industry people, Bangladesh has certain competitive advantages over its competitors in the form of availability of gas, cheap labour and the generalised system of preferences (GSP) that allows Bangladesh’s exports duty-free access to Europe. There is no quota restriction either.

Shirajul, also the managing director of China-Bangla Ceramic Industry, believes that last year’s hike in wages and gas was within a tolerable level. “But challenges lie in two other areas,” he said.

“Once the factories, which are in the pipeline, come into operation, our exports will increase several times more than our current levels. But we need a hike in cash incentive on exports to achieve that,” said the BCMEA president.

Another problem, he pointed out, is related to congestion at the port. The ceramics sector is dependent on the import of raw materials including clay, silica and alumina.

“It takes a lot of time to clear those products at the port. It has to be faster if we want to increase our exports,” said Shirajul.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments