The Name Game

When it comes to their names, most people in Bangladesh may find themselves in a convoluted situation. At least two thirds of the male population share the same first name (Abu, Abul, Abdul, or Mohammad, for example), and one third of the womenfolk generally carry a common maiden name of domestic adulation (Begum, Khanam, Yasmin, Jahan, or Sultana). Some people have nicknames and some don't; some use first names as their surnames, and prefer to go by their middle name; some have the father's first name as their family names; and some have the whole alphabet chart hanging in the neck as their name-tag. Only in Bangladesh both an Azam Khan and a Khan-e Azam would go by the same name (Azam), and there's a high chance that both their kids may end up having Azam as their last name. And then there are people with names like Abul Khayer Mohammad Wahedul Akram Patwari, who may simply go by Khokon. In most cases, our first names are not what we go by and our family names are not generally considered our last names. In short, our names somehow resemble the chaotic ambivalence of the country's cultural identity. In that convoluted chaos, what gives us a moment's serenity is our nicknames. And in my case, my parents tried their best to complicate the naming process by turning it into a game.

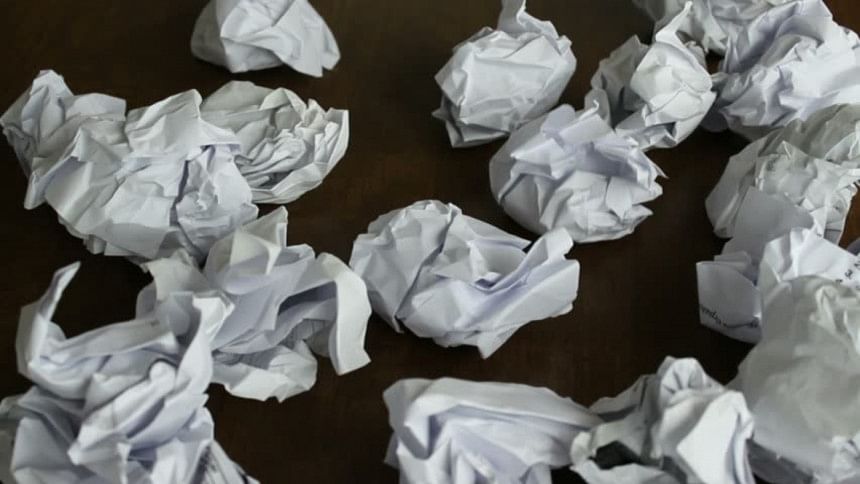

The firstborns are always hit hard when it comes to being named and I was no exception. I was born during the monsoon season, so obviously names such as Barsha, Borishon, Brishti, Nirjhora, and even Barish were on the list of possible nicknames provided by the family members. My father rejected that list completely and came up with a unique idea. He proposed to draw a lottery to choose a nickname for me and my mother went with his plan. They shortlisted six names of their choice, and my father volunteered to write those names in twelve small pieces of papers. He generously allowed my mother to be the 'chooser,' while he took the role of the 'shooter.' The rules were simple: my father would shoot the 'name dice' and my mother had three chances to pick a piece. The name that she would pick twice would win the game. Three times he rolled the 'dice,' with utmost care, making sure there was no cheating involved. And every time, my mother picked the same name.My father was shocked to see his manipulative intelligence being defeated at the hands of his seemingly docile wife. I say manipulative, because he did not play a fair game. Even though he told my mother that he had written six different names in those papers, he actually wrote two of his most favorite choices in eleven of them. Only one piece of paper had one of the three names that my mother selected. By picking the same name in all three attempts, my mother defied all laws of algorithm that he could think of. There was no logic in it, but luck. It seemed as if Destiny had favored my mother's selected name over his choices. Is there any man brave enough to defy Destiny's choice? My father therefore conceded.

Needless to say, I never likedthe nickname they gave me. Seheli. What an ugly name! My other siblings have nicknames prettier than mine—Sheuli, Kaberi, Bijoli, and Nitol. My father's nickname was Raja, and my mother's, Tuni. Even my grandmothers had Bangla names! My paternal grandmother's name was Bala (bangles) and my maternal grandmother's name was Shurjo. And here I was, a miserable girl, stamped—not once, but twice—with names imported from two different linguistic cultures (an Arabic official name and an Urdu/Hindi nickname). Why was I thus deprived? My father used to say it was my mother's luck that named me, and my mother always smiled coyly in response.

Years later, she told me the whole story. There were in fact beautiful Bangla names in their list: Shejuti, Kheya, and a few others that she did not remember any more. My father's top choice was Kheya.Even though each of them was supposed to pick three favorite names, my father later allowed my mother to pick only two. She did not like the idea that four of those six names in the list were selected by him. And then, when he came up with the lottery idea, she was furious. Who in their right mind would pick their firstborn's name from a lottery basket? She got suspicious of his generous game plan, but did not voice her suspicion. He did not let her write down those names or show her the papers when he was done writing. When she asked him to show her the papers with her selection of names, my father handed her only one piece of paper and blamed her for not trusting him. She instantly smelled a foul play and decided to teach him a lesson by beating him in his own game. She left a strong mark in that piece with her sharp nails. When he rolled his 'name dice,' she had no trouble finding the paper that had a strong pinch mark ripping through its corner. My father thought he threw a punch, but my mother defeated him with a mere pinch. After all, who can beat a woman when she is playing the game to win a name for her daughter?

Fayeza Hasanat is an author, translator, and academic. She writes regularly for the Star Literature Page.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments