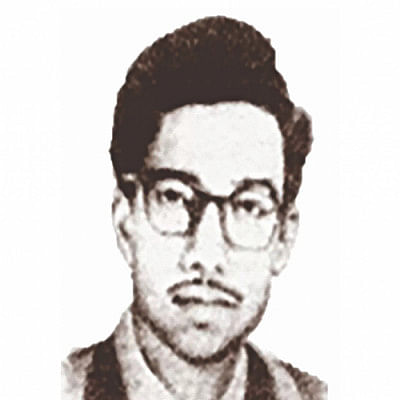

Dr Fazlul Huq Mahi- An exemplary scholar, teacher and human being

Dr Mahi, my former colleague, was an exemplary student, teacher, friend and, above all, a human being. On December 14, members of Al Badr militia force, which collaborated with the Pakistani military in its genocidal campaign, picked up Mahi from his house at Fuller Road, only to be shot dead blindfolded, along with many others.

Dr Mahi was born on August 10, 1939, in Feni. In his early professional years, he was the headmaster of GM Academy, Feni. He obtained M. Ed. from Institute of Education and Research (IER), University of Dhaka. His academic results were excellent, so much so that Jack Shaw, the then department chair, decided to recruit him as a lecturer. He was awarded a scholarship for higher studies in the United States in 1965 when we returned home after completing ours.

Mahi completed his masters and doctorate at the University of Northern Colorado, US and returned home to join as a lecturer at the IER. He was very distinct in his teaching methods, and naturally, very popular among his students.

We were colleagues in the same department. I found him very restless, busy in taking classes, discussing problems, formulating new projects, evaluating the progress of individual students, experimenting with teaching methods, preparations before entering the classroom, etc. Undoubtedly, he was very conscious politically, as was everyone at that time, but not involved with any particular political organization. We had a huge age gap—of nearly 12 years—between us, but that did not prevent us from becoming friends.

From the start of the war to the end, the ambient in and around the IER was extremely tumultuous. There were non-Bengali faculty members and staff at the department, not to mention the plainclothes spies. To add salt to injury, there were many Bangali teachers and staff, who appeared to despise the idea of becoming an independent nation. They would not hesitate to make derogatory remarks about the freedom struggle. For example, there was a teacher, namely Dr Muhammad Habibullah, who would often mock freedom fighters and the cause of independence.

Coincidentally, Habibullah and Mahi were students in the same department. They studied in the same subject in the United States. Yet, the ideological difference between them could not be starker. Mahi was a progressive teacher, liked painting and arts, but Habibullah nothing less than a fundamentalist. As the liberation was progressing, Habibullah's behaviour was growing aggressive and intimidating. Some would say that he was a deputy commander of the Al Badr militia force.

In November and December, the situation became extremely dangerous in Dhaka. By late November, Habibullah and Mahi had a bitter altercation over the liberation war and, thus, Mahi was marked. By the first week of December, the tide of the war was turning against the Pakistani occupation force and its collaborators.

We often communicated with students who actively participated in the war. Some of them would come to our house at night and warn us about imminent dangers. They advised us to leave the campus or, even better, the city. They warned us of a "blueprint" of killing academicians and intelligentsia.

I had no doubt about the severity of the danger, but where would we go, that too, in this biting cold? Nonetheless, I began looking for information as to where we could take shelter. On December 4 or 5, I met Mahi—fear was palpable in his face. It immediately struck me that something sinister happened.

Mahi was an introvert. He would not involve other people in his own problem, but standing in front of me, he seemed bitterly frightened. We immediately entered my house, and he told me about the fight he had with Habibullah. Habibullah's behaviour seemed as if he was threatening him, he told me. I asked Mahi to stay alert and tried to put him at ease.

Dhaka, by then, was in the midst of a full-blown war, with Indian warplanes regularly bombarding in the city. One of my neighbours was an Al Badr commander whose house was bombed in an airstrike. These events fuelled fear and desperation among the rank and file of Al-Badr. They probably wanted to target the intelligentsia at a later stage but when they began to sense that they were losing the war, they decided to push forward their plan.

I was receiving more news as each day when by but none of it was good. It was then that I decided that it was no longer safe to stay in the city. However, my neighbourhood was packed with so many collaborators that it was called "Dalal Para." If our entire family tried to withdraw from the area, it would surely draw attention.

Therefore, I was constantly in search of a safer exit plan. Suddenly, I came to know that Professor Aziz of the Engineering University (now, BUET) and 15-16 of his colleagues were planning to leave the city with their families. I decided that I would join them. The rest, I thought, was to be decided by the hand of fate. Subsequently, I secretly met with Anwar Pasha, Rashidul Hasan, and Dr Mahi and informed them of my plan.

Anwar and Rashidul did not want to take the risk, but Mahi agreed to come with me. We fixed the plan on the evening of December 10. We all would join at Jinjira Ghat by nine in the morning to cross the Buriganga River, and Professor Aziz would lead the journey afterwards.

At seven in the morning the next day, I went to Dr Mahi's place to check his preparations. As I was about to leave my house, I saw Rashidul and Anwar sitting in the verandah, their faces sad. They bid farewell with a silent gesture.

Mahi, however, was unprepared. Before I could say anything, he clarified that some relatives came to stay at his house and that it was not possible for him to go. I asked him to take everyone with him, but he insisted on staying. I gave up at one point and asked him not to stay at the house at night, and then I left. Little did I realise that it would be our last meeting.

At home, my wife and children were prepared. We were divided into small groups. First the kids, and then my wife and I exited home, without any belongings, in case it triggered suspicion. We reached Jinjira Ghat at nine in the morning and met with our eyes countless people desperately trying to flee the cursed city. By 11 am, we crossed the river, and just one hour later, curfew was announced across the city.

Seventeen families, with nearly a hundred members, started walking to an uncertain destination, but the fact that we were outside the city was relieving.

10-12 miles on foot, we encountered a river and found small boats that took us a bit ahead. We again started walking, and by 10 in the night, we were guests of a man known as 'Master Shaheb.' The entire area was liberated by then and freedom fighters were in effective control. The next morning, we reached the house of Professor Aziz's in-laws.

The area was not very far from Dhaka, so we still were receiving updates from the city. Suddenly, someone came with a tragic update that Munier Choudhury, Dr Shantosh Bhattacharya, Anwar Pasha, and Rashidul Hasan were picked up by Al Badr and that no one knew where they had been taken. We were still dark about the whereabouts of Professor Sirazul Haque Khan, another colleague at the IER, and Mahi.

After December 16, the day our victory was sealed, we began returning to Dhaka. As soon as we reached home, I came to know that the whereabouts of many academics were unknown.

Someone told me about Mahi. Seven or eight young men, masked and unrecognised, came in a white microbus in the morning of December 14 and picked up Dr Mahi and Dr Abul Khair.

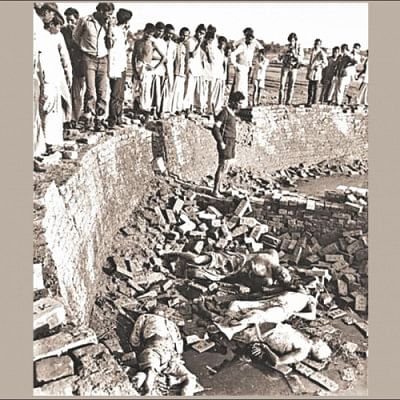

Mahi's next-door neighbour, Habibullah, witnessed the abduction from his verandah and confirmed to the abductors that they were taking the right people. Days later, several hundred dead bodies were recovered from Rayerbazar and subsequently buried around the university. That was how Mahi was martyred.

As a nation, December 14 is a tragic but memorable day in our history. Sadly, however, the way it is observed these days gives the impression that it is nothing more than a mere formality. Unless there is a movement to that change this, the sacrifice that Dr Mahi and others made will go in vain.

[Translated by Nazmul Ahasan.]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments