Shrinking revenue a growing worry

Sometimes things have to go wrong in order to go right, American author Sherrilyn Kenyon once said.

When AHM Mustafa Kamal assumed the role of finance minister on January 7, there were many things that were wrong with the economy. In other words, the stage was set for him to showcase his intellectual elasticity and can-do bravado to correct those wrongs and definitively set the economy on the right track.

“It is not difficult to address the existing problems. You will no longer see the faults that you now see,” he said in a press conference on the day he was announced as the new finance minister.

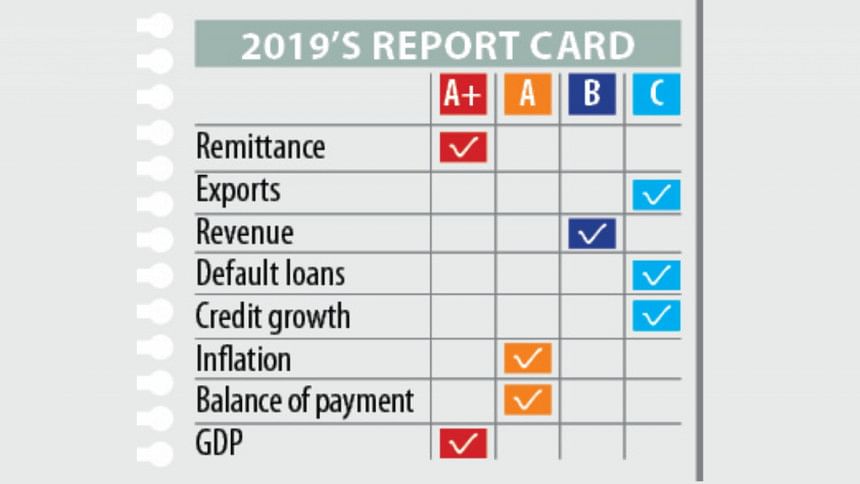

Twelve months on, cold hard data suggests that he sat by idly. When he took over, exports and revenue were on the slow lane, defaulted loans were ballooning and the stock market was sinking. Those ailments still exist and in fact have -- taken a turn for the worse.

Bangladesh’s inadequate revenue stream in comparison to the size of the economy and development works is of great concern.

At 9.2 percent, Bangladesh’s tax-to-GDP ratio last fiscal year was one of the lowest in the world and well below peers in the region. Five years earlier, it was 9.9 percent.

The ratio is likely to shrink further this fiscal year if the collection trend of the first four months and the upward slant of GDP growth are considered. Collections grew just 4.83 percent, down from 6.74 percent registered a year earlier.

Value-added tax, the largest source of revenue, was up just 1.79 percent during the period -- a worrying development particularly because the much-awaited new law that was framed to boost collections was rolled out on July 1.

The VAT and Supplementary Duty Act 2012 that passed muster for all quarters had four different rates instead of just one prescribed by the International Monetary Fund, washing away the spirit of the law.

No wonder then that the VAT collections growth thus far has been lower than a year earlier.

The VAT law was supposed to be supplemented by automation, but that has not come through yet. For instance, 25 types of businesses were supposed to be fitted with electronic fiscal device (EFDs) from this fiscal year.

At the time of writing, 10,000 EFDs have arrived at the Chittagong port out of the requisite 2 lakh, but their software is yet to come through.

“I was assured that EFDs will be installed in shops from July 1. Unfortunately, it did not happen,” Kamal told reporters earlier on December 4.

This laissez faire statement sums up best Kamal’s attitude so far in sorting out the most imperative problem of the economy.

And because of the revenue shortfall, the government had to dig into banks’ funds this fiscal year. By December 9, it has borrowed 99.5 percent of its target for this fiscal year, choking out private investment along the way.

Already, private sector credit growth hit a nine-year-low of 10.04 percent in October, 3.16 percentage points lower than the central bank’s target for the first half of the fiscal year.

Capital machinery and industrial raw material imports have shrunk too, according to Bangladesh Bank’s latest data.

Banks’ ability to lend had already taken a big hit because of the runaway defaulted loans and then came this new pressure from the latter half of 2019 in the form of heightened government borrowing.

“As of today, what is on the balance sheet will remain the same -- it will not increase in anyway,” Kamal told a press briefing on January 10, soon after taking charge of finance ministry.

But, the situation of defaulted loans has only gotten worse in 2019.

Another setback arising out of the slowing revenue collection is that the government’s budget deficit crossed the sensible perimeter of 5 percent for the first time in 12 years in fiscal 2018-19, and is on course to breaching it again this fiscal year if the root cause is not fixed with urgency.

Thrift is of great revenue, Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero once said, and the government would do well if it pays heed to this saying, now.

Implementation of development projects continues to come about at snail’s pace, leading to cost overruns. And the government’s subsidy burden is only getting heavier, and if the duty waiver to certain sectors are factored in, it seems indulgent in times of revenue shortfall.

Another worrying development is the continued slowdown in exports, one of the lifelines of the economy, thanks to a contraction in garment orders on the back of strengthening competitors and the US-China trade war.

This episode is not an eyeopener but just a reconfirmation of what the experts have long been warning: excessive reliance on one item is not wise and neither is complacency.

Moving up the garment value chain has long been advised for Bangladesh’s garment sector, but the country’s apparel exporters were just happy with the global monopoly for low-value, basic products.

This has opened the floor for upstarts to challenge Bangladesh’s second position in global apparel trade. And Vietnam, India, Turkey, Pakistan, Cambodia are not squandering this opening.

Their time to export is much shorter than Bangladesh’s: it takes 315 hours, in contrast to 105 hours for Vietnam and 81 hours for India. It takes 180 hours for Cambodia and 130 hours for Pakistan.

Looking ahead, if the problems causing slowing revenue, shrinking exports and runaway defaulted loans are not addressed at the soonest, 2020 looks sets to be a bumpy ride.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments