Bangabandhu speaks to the world

“Sir, we had been praying for you.”

With tears in his eyes, an on duty British police officer outside the VIP lounge of London’s Heathrow airport addressed Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as he along with Dr Kamal Hossain and his family were escorted from the special Pakistan International Airlines aircraft to the lounge.

Earlier, Pakistan’s new President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto bade farewell to the newly freed founding father of Bangladesh at Chaklala airport in Rawalpindi.

Bhutto took over power from President Yahya Khan a few days after Pakistan army’s defeat in the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 and announced Bangabandhu’s release in the face of tremendous pressure from the world community.

As the special aircraft carrying Bangabandhu took off in the deepening night, Bhutto said to no one in particular, “The nightingale has flown.”

The plane landed in the Heathrow airport in a chilly frosty morning on January 8, 1972. Bangabandhu stepped out of the plane as a free man after having spent over nine agonising months in Pakistani jail.

Entering the VIP lounge, an announcement of a telephone call for “Sheikh Mujibur Rahman” was heard. Bangabandhu asked Dr Kamal to take the call.

At the other end of the phone was lan Sutherland of the British Foreign Office, who told Dr Kamal that the British government had received a message regarding their arrival only an hour ago. He had, however, taken immediate steps to receive Bangabandhu.

Alerted by the British Foreign Office about the development, MM Rezaul Karim, who was then acting as head of the unofficial Bangladesh Mission in London, started driving down to Heathrow.

While waiting at the lounge, the Pakistan High Commissioner, Nasim Ahmed, a former journalist, came and told Bangabandhu, “Sir, I am here to welcome you. Please let me know what we can do for you?”

“You have done enough, thank you very much,” Bangabandhu replied.

Within a few minutes, Ian Sutherland had arrived and conveyed the British government’s warm welcome to him.

He said that arrangements had been made for accommodation at Claridge’s Hotel, where heads of state were normally accommodated.

Bangabandhu thanked him but asked if it would be possible to arrange his stay at a modest hotel in Russell Square, where he had stayed on earlier visits to London.

Sutherland replied, “Sir, this is the only thing I cannot arrange, because heads of state’s security can only be provided at Claridge’s Hotel. But we will see that any number of people who want to see you can do so, subject to security measures.”

In the meantime, Rezaul Karim had arrived.

On his arrival, the Pakistani officials flying with Mujib saluted the undisputed leader of independence of Bangladesh and left the room, their job done.

Bangabandhu, as Rezaul Karim was to relate years later, declined to use the official limousine placed at his disposal by the British government and instead rode with Karim in his car.

Karim, who was driving through the cold winter morning, was both excited and alarmed. Excited because in an incredible way he had become the first Bangalee to have met his nation’s leader for the first time since March 1971; alarmed because Bangabandhu kept asking him questions about the war and how Bangladesh had been liberated and Karim was afraid lest his car meet with an accident and cause fresh new tragedy.

On their arrival at Claridge’s Hotel, Bangabandhu spoke to his family, Syed Nazrul Islam and Tajuddin Ahmad in Dhaka.

Syed Nazrul and Tajuddin informed that an aircraft to fly for London from Dhaka could be arranged but it would take at least two days for it to reach London.

They had also been informed that the people of India were extremely keen for a short stopover in Delhi and Kolkata, on the way to Dhaka.

At the hotel, a problem arose about how to accommodate requests of thousands of people to see Bangabandhu. It was then decided that groups of five persons will be allowed to visit him at a time.

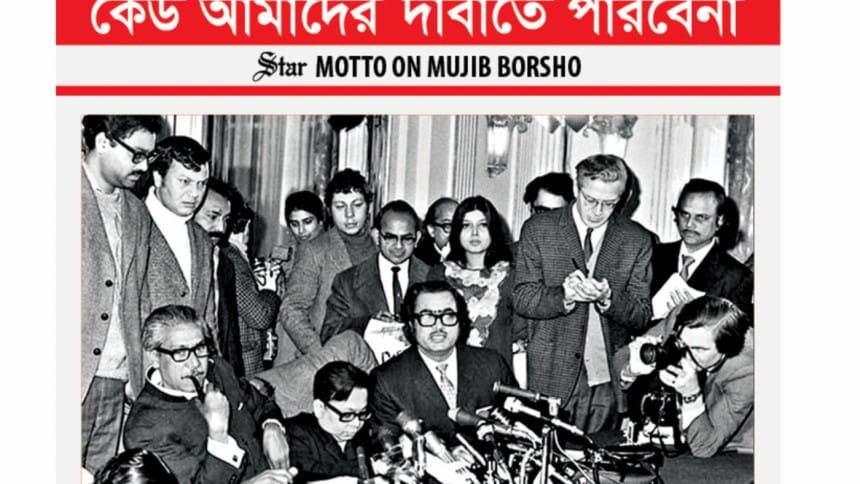

Later, Bangabandhu addressed a crowded press conference at the hotel.

“Today, I am free to share the unbounded joy of freedom with my fellow countrymen. We have won the freedom in an epic liberation struggle,” he said.

“The ultimate achievement of this struggle is the creation of an independent, sovereign, People’s Republic of Bangladesh of which my people declared me as the President while I was a prisoner in a condemned cell awaiting the execution of a sentence of hanging.”

He went on: “No people has had to pay as high a price in human life and suffering for the freedom that has been exerted from the people of Bangladesh. I cannot wait a single moment to return to my people.”

His speech followed questions from journalists.

One of the journalists asked about how he felt after being held by West Pakistan and at any time were they considering executing him, Bangabandhu replied, “I was mentally ready for that. A man who is ready to die, nobody can kill him, remember one thing.”

Another newsman queried as to when he was aware that Bangladesh had been liberated, Bangabandhu said, “I am doing politics for about 35 years. The day I went to jail, I know whether I will be alive or not, my people of Bangladesh will be liberated; nobody can stop it.”

In the evening, Bangabandhu met the then British Prime Minister, Edward Heath, at 10 Downing Street.

At the meeting, Bangabandhu raised the question of the British recognising Bangladesh as a sovereign country.

According to a declassified document of the US Department of State, Heath told the then US President, Richard Nixon, in a message on January 13, 1972, that “…he [Mujib] spoke with confidence and assurance. He was anxious to reach Dacca as soon as possible…”

“Mujib told me that there can now be no question of a formal link between Bangladesh and West Pakistan. He had said the same to Bhutto prior to his release. In this he has confirmed the position of the Bangladesh authorities in Dacca and our own assessment of the state of affairs in the East.”

“However, although he spoke with understandable bitterness of the actions of the previous Pakistan regime, he showed no rancour towards Bhutto, and said that he wished to establish good relations with West Pakistan,” reads the British Prime Minister’s message for Nixon.

“The new partition should be, in his words, “a parting as of brothers”, but Bhutto had to acknowledge the division of Pakistan. Relations between the new Bangladesh and India would of course be much closer,” it said.

The declassified document also showed Bangabandhu spoke of his hope of Commonwealth membership and the British Premier assured him of their goodwill, but at the same time explained the reasons why they could not recognise Bangladesh at once.

“He shared our wish for harmonious relations between Britain and the three countries of the Indian sub-continent and he hoped that we would help to persuade Bhutto to accept the realities of the situation,” it said.

When Heath asked Bangabandhu what else they could do for him, Bangabandhu’s prompt reply was, “Yes, you can do one more favour, if you could kindly help us with a plane to take us to Bangladesh as soon as possible.”

Bangabandhu returned to the hotel after the meeting. Calculations were made for the time it would take to reach Dhaka as Bangabandhu intended to reach Dhaka while there was still daylight.

And it was figured out that only one stopover was possible in India, if they were to arrive in Dhaka by 3:00pm. It was then decided that it would only be possible to stop over in Delhi.

The British Royal Air Force comet jet war ready to carry Bangabandhu home via Delhi. In the early morning of January 9, Bangabandhu was whisked away for the airport.

At about 6:00am, the British comet took off for Nicosia, for refuelling, en route to New Delhi for its final destination of Dhaka.

[The report is based on the autobiography of Dr Kamal Hossain titled “Bangladesh: Quest for Freedom and Justice”; an article of MM Rezaul Karim published in The Daily Star; and declassified documents of the US State Department]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments