The Return of the Hope

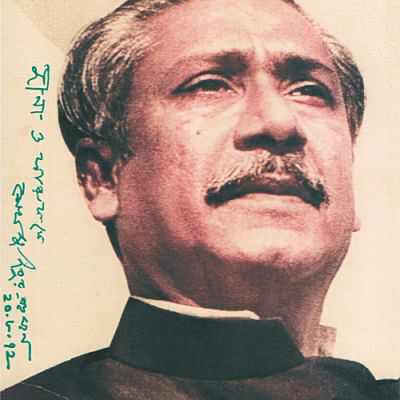

On January 10, 1972, the man whom his people lovingly called Bangabandhu, friend of Bengal, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, returned to Dhaka on a chilly and windy late afternoon from London, via New Delhi, to be welcomed by hundreds and thousands of people. Mujib was taken as prisoner when the Pakistani army launched the “Operation Search Light” on the night of March 25/26, 1971, to annihilate the people of Bangladesh. While the country burned for the next nine months and our Mukti Bahini fought to free the country from Pakistani rulers, Mujib was being tried in a Martial Law court in the Pakistani city of Mianwali, charged with 12 counts of crime, some of which carried the death penalty.

But luck was not in favour of the Pakistani Junta. Before Yahiya Khan could execute Mujib, he lost half of Pakistan and was on the verge of losing the other half. He was thrown out of Pakistan’s presidency to be replaced by Pakistan People’s Party Chief Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. After assuming the presidency Bhutto released Mujib from prison and Mujib was sent to London on a special PIA flight. Mujib arrived at Heathrow in the early hours of January 8, 1972 to return to Dhaka on January 10.

After his return to Dhaka from Pakistan’s captivity, he met a group of foreign journalists on January 16 in the old Gonobhavan where he and General Yahiya sat for their dialogue on transferring power to the elected representatives following the 1970 general election. Mujib narrated the incidents following the night of March 25/26, 1971, the night when the “Operation Search Light” was launched to annihilate the people of East Bengal. Sydney H Schanberg, one of the journalists attending that briefing, wrote in the New York Times (published on January 18, 1972) quoting Mujib, “He kissed his weeping wife and children goodbye, telling them what they knew too well, that he might never return. Then the West Pakistani soldiers prodded him down the stairs, hitting him from behind with their rifle butts. He reached their jeep and then, in a reflex of habit and defiance, said: ‘I have forgotten my pipe and tobacco; I must have my pipe and tobacco!’ The soldiers were taken aback, puzzled, but they escorted him back into the house, where his wife handed him the pipe and the tobacco pouch.” By the time Mujib was taken away inside the Dhaka Cantonment, he could see the city he loved and spent a great part of his political life in, Dhaka, in flames.

Mujib was flown to Rawalpindi via Karachi on April 1 and then moved to Mianwali prison and put in a cell. He passed the next nine months alternating between that prison and two others—at Lyallpur and Sahiwal—all in the northern part of Punjab province. The military government began proceedings against him on 12 charges, one of which was “waging war against Pakistan.” Pakistan’s ruling civil-military clique always wrongly read the people of East Bengal. They read them wrong in 1948, in 1952, in 1962, in 1966, in 1969, in 1970 and finally in 1971. They never realised that this is a nation that has overcome the fear of death. And a nation that has conquered the fear of death can never be killed.

During Bangabandhu’s absence, a six-member government in exile was formed—commonly known as the “Mujibnagar Government’—on April 10, with Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as president and Syed Nazrul Islam as the vice-president. He would assume the role of acting president in the absence of Bangabandhu. Tajuddin Ahmed was made the prime minister in the cabinet, with Mansur Ali, AHM Qamruzzaman and Khondakar Mostaq Ahmed being the other members. The election of the first cabinet of Bangladesh was made by the elected members of both national and provincial assembly. The cabinet took the oath of office on April 17 inside Bangladesh, in a place called Baiddanath Tala in Meherpur, later to be renamed as Mujibnagar. This cabinet was instrumental in making all the policy decisions during the nine-months long Liberation War that ranged from gaining international support to managing the battlefronts.

While the government in exile was busy with affairs of liberating the country, Pakistan’s military junta was busy preparing to execute Mujib. In August the so-called trial in a military court began. The sole aim was to stage a judicial murder. Mujib demanded he be defended by the eminent jurist AK Brohi, but after a few court sessions, it became clear to Mujib that the Junta “just wanted a certificate to hang me”, Mujib narrated to a foreign correspondent on January 16, 1971. Mujib asked Brohi not to be a part of this sham trial. By the time Yahiya took the decision to hang Mujib, the Pakistani military junta and Yahiya Khan ran out of time. Our valiant freedom fighters, with the help of the Indian army, had liberated Bangladesh from the Pakistani occupation forces and whatever remained of Pakistan was virtually being occupied by the Indian forces. On December 16, the Pakistan army surrendered to the joint forces in Dhaka. General Yahiya was forced out of power and Pakistan People’s Party Chief Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto assumed the office of Pakistan’s President and Chief Martial Law Administrator. As a matter of fact, after the general election of 1970, Bhutto wanted it that way. He would always say “Edar Hum Odar Thum” (I rule here and you (Mujib) rule there). Yahiya wanted to hang Mujib on December 16. Because of the timely intervention of the Mianwali Jail Superintendent, the tragedy could not be enacted.

After Bhutto took over, he released Mujib, who was taken to a Presidential Guest House in Rawalpindi, where he met him a number of times to desperately try and stitch the wounds opened over the previous nine months. He wanted Mujib to agree to forge a confederation between Pakistan and Bangladesh. Bhutto was no match for Mujib’s political maturity. In clear terms Mujib said he must first go back to his people, talk to them and do what they desire. Bhutto declared Mujib was a free man and could go wherever he wanted. Mujib chose to fly to London. In the early winter morning of January 8, a special PIA flight touched down at Heathrow airport. The new president of a new country was received by a few Bangladeshi diplomats and a senior officer of the British Foreign Office. After being briefed by the young Bangladeshi diplomats he addressed a crowded press conference before leaving London for New Delhi en route to Dhaka. Disregarding all standard protocols, Mujib was greeted in New Delhi both by Indian President VV Giri and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. After a brief stopover in New Delhi, Bangabandhu left for Dhaka. It was late afternoon when the symbol of Bengalee nationalism and the founder of a new country came down the stairs of the aircraft to land on the soil of the country for which he fought his entire life. 75 million people waited for this historic moment.

Bangabandhu’s return was significant for many different reasons. First it was his charisma and leadership which made Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi pull out the Indian troops from Bangladeshi soil by March 26, 1972. During the war, thousands of firearms were distributed amongst the freedom fighters. It was due to Bangabandhu’s call that the freedom fighters returned their weapons. During the nine months of the Liberation War, there were power struggles within the rank and files of those involved in the war. Though the first cabinet was formed with the support of the elected members of the parliament, everyone was not happy with the members chosen. Some members of the Awami League wanted a cabinet with more diverse and young members. Those freedom fighters that came from the defence wanted a Revolutionary War Council, a wartime cabinet comprising of only military officers. Leaders from other political parties wanted a National Government with leaders taken from all parities instead of an Awami League led government. Such divisive thinking persisted till the return of Bangabandhu. It was only due to his towering personality and hypnotic leadership that things did not get out of control.

Abdul Mannan is former Chairman, University Grants Commission of Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments