Demystifying the data-governance conundrum

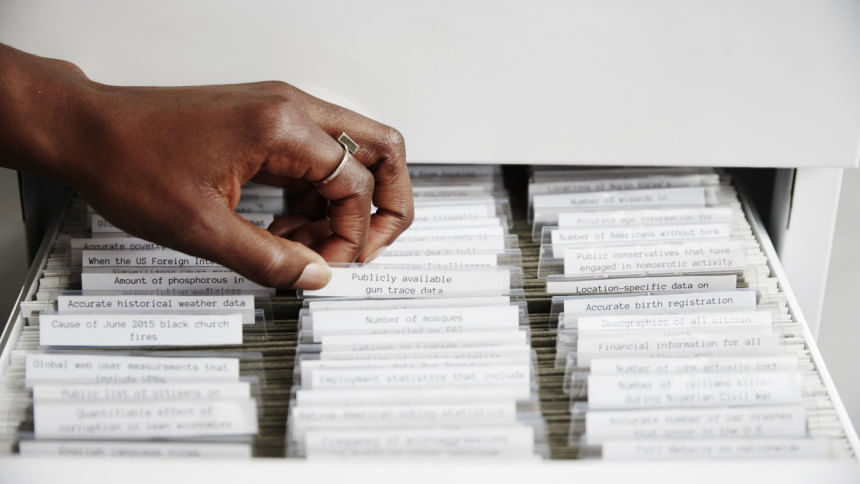

Mimi Onuoha, an artist and adjunct professor at New York University, made an art installation titled "The Library of Missing Datasets". Her aim was simply intriguing, punctuated by the thought that "wherever large amounts of data are collected, there are often empty spaces where no data live". Deep down, this depicts our very system,which makes for the preponderance of cherry-picked data while leaving the unpleasant ones unattended. This, in turn, provides pressure groups with the opportunity to shift the blame onto the data-governance system used because sometimes, absence of particular data looks like a deliberate act of omission by the authorities concerned.

In this ever-evolving world, intertwined by terms like big-data, data analytics, data crunching and what not, we are literally swimming in an ocean of data. However, while navigating the tricky path of data on myriad fronts, finding appropriate data appears to be a major challenge coupled with its accessibility, relevance, and quality. This situation is amplified when it comes to the developing world and Bangladesh is no exception in this regard. Moreover, it acts as an overarching reminder that sometimes the vulnerable aspects in a socio-economic setting can be near-invisible to policymakers because data pertaining to those aspects do not always provide statistical comfort and thus, they remain missing in efforts to quantify.

Coming back to Bangladesh, inadequate and sometimes contradictory data on important indicators dent stakeholders' confidence, and such contradictions lead to mistrust. Additionally, data from sources other than that of the government are being largely overlooked. Moreover, existing data generation and target-setting principles are believed to lack acceptable standards and practices. Therefore, stakeholders often face challenges in agreeing upon what sources to follow and what data to accept. Eventually, this confusion often ends in a cul-de-sac.

All of us might be aware of the fact that the government of Bangladesh started its policy planning with an agreed principle to see its formulation through an 'SDG lens'. The United Nations stated that data will be crucial to tracking the progress of SDGs and in formulating a monitoring and evaluation framework for the implementation of the SDGs. However, Bangladesh is already facing a significant data gap for tracking the SDGs, as statistics on two-thirds of the indicators are either partially available or not available at all, according to a report titled "Data Gap Analysis for SDGs: Bangladesh Perspective" conducted by UNDP Bangladesh. The study underscored that there are 241 indicators to monitor the 169 targets under 17 SDGs, but data of only 70 indicators are readily available, 108 partially available and 63 not available at all.

However, the data gap situation seems to have improved a bit when Bangladesh published its first progress report on the SDGs. According to the report, around 30 percent of indicators had readily available data, while 47 percent had partial data or required further analysis of raw data to reach useful conclusions on respective indicators. Maybe, inclusion of the UN system and other international agencies as data providers have helped in curtailing some data gaps.

The data-gap issue is prevalent in other areas too. For instance, a large gap in the total tax revenue collection data between the National Board of Revenue and the Controller General of Accounts office puzzles the government every year. This prompted the authorities concerned to establish an institutional partnership for addressing the discrepancy in revenue collection data. Additionally, areas like trade, investment, manufacturing, financial markets, informal sector, poverty, employment etc. all come up with contradictory data.

We must understand that in any setting, data sits in multiple systems, separated by technical and functional boundaries. The principle strategy to complement this setting will be to undertake collaborative reforms and implement a comprehensive set of activities to enhance the capacity of relevant agencies to produce data within their boundaries. This collaboration would lead to opportunities for evidence-based policy making and implementation. Moreover, regular interactions between researchers and policymakers and sharing each other's perspectives is imperative. It is evident that by contextualising research within the development landscape and by translating data into evidence, researchers help policymakers embrace research-backed policy actions for greater impact.

However, mainstreaming researchers in to policy planning depends on the way government, relevant stakeholders, and the civil society understand the dynamics of research and researchers. Apparently, researchers are often perceived as thought-leaders speaking in a language only understood by their peers and thereby, they are often seen isolated from the wider development conversation. This results in a situation where their efforts are not necessarily translated into evidence for the decision-making hierarchy and thus fails to create impact commensurate to its true potential. Moreover, the very apparent industry-academia gap is another stark reality prompting data discrepancy.

Additionally, there is an urgent need to map institutional expertise and capacities for better collaboration and resource use, since different agencies are seen working on the same resources using the same technology, meaning overlapping efforts and waste of resources. Moreover, the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, the national statistics agency, along with several other agencies such as NIPORT, DoE, DAE, BFD, BANBEIS, BB, EPB, NBR, DGHS etc., require tailor-made support for dealing with new types of data analytics as well as for embracing allied technologies.

"Data Governance" is a happening term right now and good data does matter to get a grip on this. Harnessing the true potential of data by translating it into evidence can not only further its impact, but also help in defining holistic development.

Sabbir Rahman Khan is a Research Associate at the Bangladesh Foreign Trade Institute (BFTI)

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments