The 9 per cent cap will hurt the financial inclusion agenda

Banks prefer to work with large national and multinational business groups and the government, which offer less risk and higher returns.

Small firms face high interest rates due to high risk associated with them.

It is generally more difficult for small and medium-sized companies to obtain a credit than the large ones, especially due to an insufficient amount of information needed by banks to assess the opportunity for a loan.

Financial institutions impose higher than normal lending rates to cover themselves against inadequately assessed risk. Small firms cannot access finance due to lack of collateral, market access, inadequate infrastructure, low research and development capacity and inadequate managerial knowledge and skills.

Small firms also face enormous problems in acquiring technology and adopting innovative ideas in management and production of goods and services.

All these impediments to their start-up, and the ability to survive and prosper undermine their credit worthiness.

High interest rates charged to these borrowers are a consequence of the riskiness of investing in such enterprises.

It is a signal that interventions are needed to address the sources of the risk, not gagging of the signal itself.

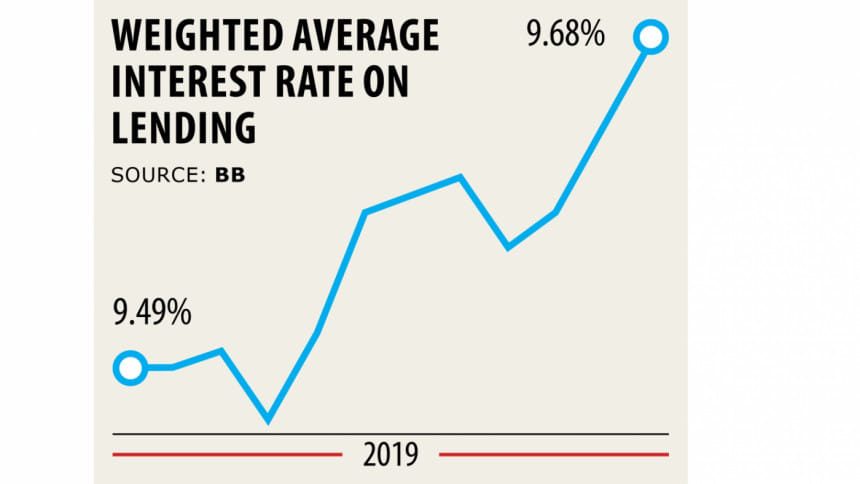

A 9 per cent cap on lending rates is scheduled to become effective from April 1 for all loans except credit cards. The cap will restrict lending rates for Cottage, Micro and Small Enterprises (CMSEs).

The restriction is intended to encourage further growth in this segment by enabling them to access credit at lower than the average 16 per cent rate charged for collateral-free financing to CMSEs.

While the intentions are noble, the unintended consequences may be the opposite because of several reasons.

Successful CMS financing requires the implementation of an Intensive Supervisory Credit framework which, in turn, requires a very large workforce and infrastructural facilities.

This results in high cost to income ratio, which is approximately 84 per cent across the CMSE banking industry.

Such high operating costs can only be recovered through higher lending rates and higher interest spreads.

The 9 per cent interest rate cap will not cover the costs and risks, thus resulting in the sector’s CMSE portfolio becoming commercially unviable overnight.

This will discourage banks from further lending and quickly reduce the supply of credit to these customers, forcing them to borrow from unofficial predatory lending sources such as traditional moneylenders.

Their production and operations costs will spiral, thereby impacting a large part of the local economy.

CMSEs provide 7.86 million jobs. By slowing down business, reduced funding to CMSs will increase unemployment not only in that sector but also in the banks who finance such businesses. Over 12,000 bankers support this customer segment.

Financing CMSEs is an important enabler to the country’s overall financial inclusion agenda.

Hundreds of thousands of small entrepreneurs are brought into the banking umbrella through CMSE financing. This sector has been a top priority of the government and the Bangladesh Bank.

The BB has required that Banks migrate 25 per cent of their funds into the Cottage, Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise (CMSME) sector within the next few years.

The traction across the banking sector so far has been below this target, with some exceptions.

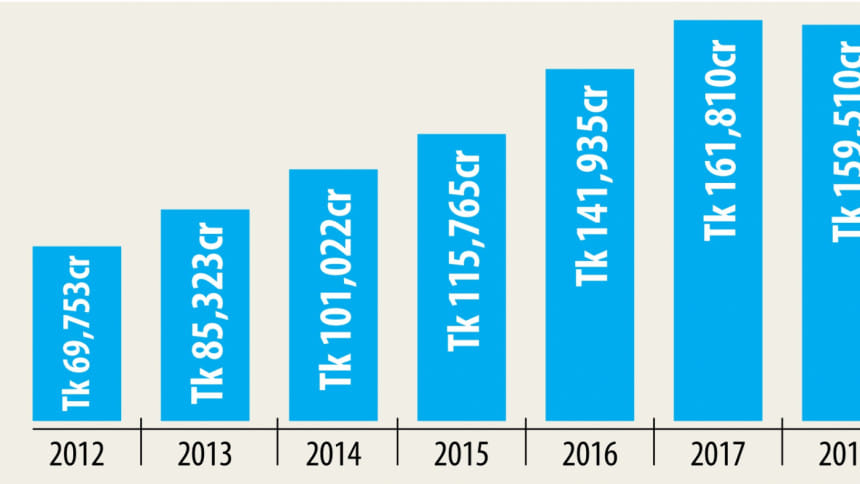

Outstanding stock of CMSME bank loans constitute about 19 per cent of total stock of bank credit to the private sector and out of that CMS Sector constitute 13.5 per cent, according to BB SME Data of September 2019.

A reduction of CMSE lending rates to 9 per cent will not only discourage the banks from rolling over these loans to the same sector but also from extending additional loans to move closer to the target.

How well founded are these apprehensions? We can only draw from international experiences to get some idea.

The literature on interest rate ceilings suggests they create several problems: (i) reduced access to credit to small borrowers who tend to be riskier and costlier to manage; (ii) as access to bank credit is curtailed, potential borrowers turn to informal lenders that charge much higher rates and are not subject to regulation leading to more, not less, predatory lending; (iii) reduced transparency as lenders institute non-interest charges, such as fees, to compensate for lower income from loans making it more complicated for customers to understand the total cost of borrowing; and (iv) adversely affect the viability of small and medium-sized banks, whose business model relies on attracting deposits at higher interest rates and lending to high cost/high return small enterprise sector, thus elevating risks to financial stability through contagion effects.

Specific examples of how these problems have manifested themselves include withdrawal of financial institutions from the poor or from specific segments of the market, especially for small borrowers that have higher loan management costs for banks, such as rural clients and women with low collateral.

The most known instances of such experience can be found in Bolivia, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Haiti, Nicaragua, Peru, Poland, and Zambia.

Lower access to small borrowers leads to increase in loan size after the imposition of caps as seen in Bolivia, Ecuador, South Africa and Zambia. A proliferation of fees and commissions reduced the transparency of the cost of credit most visibly in Armenia, Nicaragua, South Africa and Zambia.

Bangladesh needs its banking sector to significantly increase funding for CMS customers and invest in new technologies as well as processes to grow the business.

Any policy change that creates a commercially unviable CMS framework in the banking sector will prove to be retrogressive.

The priority must be to improve access to credit at this stage, not cost of credit. Once the sector has achieved an appropriate level of CMS financing, e.g. the 25 per cent required by the BB, and acquired reputational capital, the cost of credit will begin to decline.

Banks behave differently towards mature entities in the competitive market. They charge a lower rate for credit as trust builds and risk perceptions moderate.

The adverse effects of lending rate ceiling can be avoided if the ceiling is high enough to facilitate lending to higher-risk borrowers.

One option could be to set the ceiling at the average of past monthly commercial rates plus a margin. This margin would need to be sufficient to avoid rationing out high-risk borrowers.

The sufficiency can be judged on the basis of rate differences in peer countries.

Rates charged to CSMs are on average 70 per cent higher than the corporate and commercial rates in India, Malaysia and Thailand. Such adequate margin inclusive ceiling on rates for CMSEs should apply to new loans and rollover of the legacy loans.

Setting the lending ceiling in this manner would stop the most egregious forms of predatory lending, while still providing sufficient margin to compensate for risks.

Over the past several decades, interest rate controls have been relaxed in most countries. The focus has shifted mainly to protecting vulnerable borrowers from predatory lending practices.

The author is an economist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments