Outmoded tariff act holding back insurance sector

A staggering 46 non-life and 32 life insurance companies are licenced to operate in Bangladesh and yet there is virtually no local underwriting expertise or capability within the country.

The market remains regulated by tariff, which is outdated and handed down from the British era. This has prevented the development of local expertise in underwriting.

The sector is unable to draw upon local talent to join the industry as there is virtually no scope for innovation, risk assessment calculations or pricing based on intelligence.

The combined premium revenue in Bangladesh from life and non-life insurance is slightly over $1 billion, and approximately a third of which is from non-life insurance.

In contrast, our neighbouring country India, which liberalised the insurance market in 2000, licenced only 33 insurance companies in non-life and 24 in life insurance sector.

The total market size of insurance in India today is close to $100 billion.

The insurance sector in India was regulated by the tariff too until 2000, which clearly prevented modernisation and innovation.

It is no surprise that today if you watch Indian cable TV channels, a significant portion of the advertisements are from the insurance sector encouraging one to insure everything -- from life, savings to lost luggage's.

Liberalisation of the insurance industry in India helped facilitate India's growth.

In addition, it attracted better talent to the industry, who developed local actuarial and underwriting capability and capacity.

Seeing great prospects for growth and development of their career in insurance, students felt encouraged to join the insurance, reinsurance and broking industry.

As it stands today in Bangladesh, commission is currently the only game of play, as there is no real understanding of risks or the underwriting of risks.

The Insurance Development & Regulatory Authority (IDRA) has taken positive steps in curbing -- or trying to control -- the maximum allowable commission across the board.

Reducing the levels from up to 70 per cent reported at various instances in life and non-life insurance sectors was, indeed, a strong step in the industry.

However, there are reports of insurance companies still paying higher commissions, primarily under the enforcement or order of their directors and shareholders.

This is unlikely to change until there is a proper understanding of risks through the process of underwriting.

Currently, the role played by the private insurance companies towards insuring a particular risk depends on the total sum of insured value (TIV).

If the TIV is below Sadharan Bima Corporation's (SBC) country limit (for example, Tk 400 crore for property damage), the insurance company will look up the published tariff rate and issue the policy.

If the rate is above the country limit, the insurer will then seek rates, terms, conditions from foreign Facultative reinsurance underwriters (Reinsurance Company), either via SBC or directly.

The reinsurance underwriter will then provide their rate of premium based on which the local insurance policy will be issued.

In other words, there is very little scope for actual assessment of risks, and therefore negligible scope for local underwriting.

The role played by SBC is also similar. Due to specific treaty understandings and limits set between the private insurance companies and SBC, SBC is generally required to accept and consume the insured value up to its treaty limit.

Again, there is virtually no scope for due process of underwriting, as the policy is issued under the published tariff rates.

If the TIV is above the treaty limit or the country limit, SBC can reach out to foreign facultative reinsurance underwriter for rates and terms.

As per the regulations, all private sector companies must cede at least 50 per cent of their reinsurance portion to SBC.

More than 80 per cent of the local insurance companies are fully reliant on SBC, who in turn is also virtually reliant on foreign reinsurance underwriters for both treaty and facultative rates and terms.

As a result, most of the private sector insurance companies feel there is no real need to develop their own underwriting capabilities.

The foreign reinsurance underwriters have a choice to accept or reject a risk based on his or her risk appetite. If accepted, the underwriter can, and obviously will, offer rates, terms and conditions favourable to them.

While insurance is the process of sharing, transferring or assuming risk exposures by an insurance company, reinsurance is the process through which insurance companies insure themselves.

Given the fact that there are only a handful of foreign reinsurers willing to write risks in Bangladesh (due to various reasons, including lack of information, size of risks, transparency, country risks, KYC reports, natural catastrophe exposures and so on), local insurers are often faced with difficulty in finding reinsurance placement.

Consequently, the role played by the international reinsurance brokers is also made difficult as the local market does not fully understand (1) how reinsurance underwriters develop rates, and (2) how international reinsurance placement is actually done.

While brokers are indeed eager to place business coming from Bangladesh, they are invariably faced with multiple insurers approaching the same handful of reinsurance underwriters with the same risk bearing little underwriting information.

The foreign reinsurance underwriters feel frustrated and reluctant to offer favourable terms. As a result, the rate is often less competitive than the global market rates.

If the insurance industry wants to claim its rightful place within the economy, we must develop local underwriting expertise.

In order to do that, we must invest in training and developing underwriters. This may be achieved by investing in scholarships for the ACII (Associate of Chartered Insurance Institute of the UK) or the CPCU (Chartered Property & Casualty Underwriter of the US).

We must also invest in training of teachers at the Bangladesh Insurance Academy (BIA) so that they may impart undated knowledge and technical know-how to the students of insurance.

Encouraging and investing in students to become actuaries so that they may serve the country need to be done, too.

Without Actuaries, we cannot develop rates that take into account local exposures, environment, and statistics, particularly for life insurance.

Populating the IDRA and the rating committee with experienced underwriters and personnel who have practical experience in modern insurance and reinsurance practices, in-depth understanding of policy wordings, their historical development and legal implications can be done.

We must also abolish the local insurance tariff. The tariff rates, which were essentially handed down from the Insurance Act of 1938, do not reflect updated knowledge or statistics.

The tariff does not respond adequately to newer exposures such as trade credit insurance, mobile telecommunication, power generation, satellite, terrorism, cyber, fintech, and several other modern risk exposures.

This compels local insurers to approach foreign underwriters.

Our local insurers need to be stimulated to learn how underwriters generate rates and terms. The tariff is holding us back by discouraging curiosity to grow.

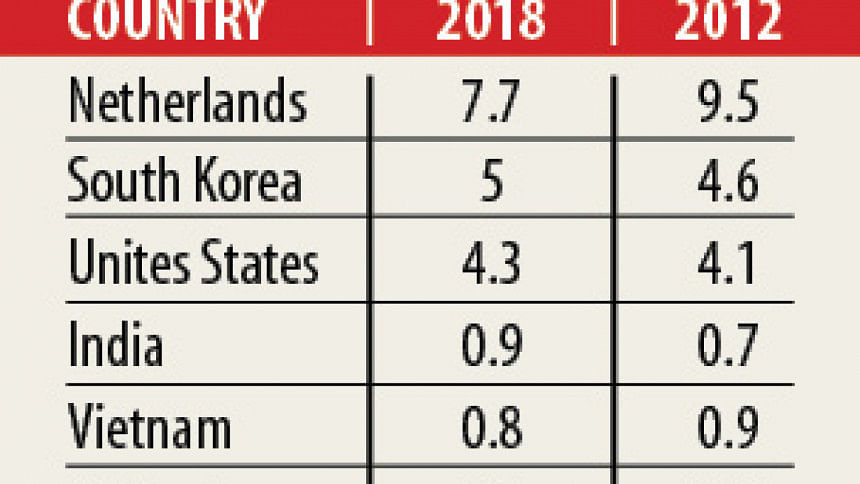

The Bangladesh insurance sector is lagging behind the world and even our neighbouring countries.

Banking and insurance work hand-in-hand for all trade finance, infrastructure projects, imports and exports.

Because of our poor understanding of insurance underwriting, we are agreeing to insurance terms that are often detrimental to our country and economy.

If the country and its private sector industries want to continue to grow rapidly, it will need a vibrant insurance sector.

Consequently, the insurance sector must also be ready to respond to the needs of the modern economy.

Insurance sector development is an urgent need of the time. Our local underwriting capability and capacity must be elevated to respond to such needs.

MR Khan is a specialist with 25 years of experience in risk management, insurance, and reinsurance. He is currently the chief executive officer of Integrated Risk Consulting Group (iRCG).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments