21st century skills and the 4th Industrial Revolution

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina recently said, "It is not only Bangladesh, the whole world will need skilled manpower… and for that we have reformed our education system, giving priority to vocational training." She was speaking at the international conference on "Skills Readiness for Achieving SDG and Adopting Industrial Revolution 4.0" on February 2, 2020. The event was organised by the Institute of Diploma Engineers Bangladesh (IDEB) and the Colombo Plan Staff College in Manila, Philippines.

The Prime Minister has rightly indicated an important priority. The question is: how are buzzwords such as the "Fourth Industrial Revolution" understood and what is happening on the ground in the thousands of secondary level institutions across the country?

Klaus Schwab, the founder of the World Economic Forum and the organiser of the annual Davos Summit, is credited with popularising this term. As Schwab explains, the First Industrial Revolution started in the 1780s, using water and steam power to mechanise production. The Second, beginning in the 1870s, used electric power to create assembly lines and lead to mass production. The Third, starting from the 1960s, used electronics and information technology, also known as digital technology, to automate production. The Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) now builds on the digital revolution.

The latest Industrial Revolution blurs the lines between the physical, digital and biological spheres in an unprecedented way. The 4IR is radically different, since it is more than only a technological shift in economic production, as the previous three were. It opens unlimited possibilities for addressing critical challenges of poverty, inequality and sustainable development. However, beyond the hype surrounding 4IR, the potentials and challenges have to be seen from the perspective of the real world, especially from the point of view of low income countries like Bangladesh where the majority of the world's people still live. The prospects and problems are spectacularly different for most people in these countries when compared to those in wealthier countries.

Over 80 percent of our workforce are employed in the informal economy, which is not regulated by worker welfare and rights standards. A third of the workforce has no education, 26 percent have only primary education and 31 percent have only up to secondary education, according to a 2017 Labour Force Survey. Over 40 percent of workers are engaged in the low-skill and low-wage agricultural sector. The concept note for the Eighth Five Year Plan (FY2021-25) that is under preparation says that the overall quality of the labour force is much below the level that is needed to achieve the planned 15 percent growth in manufacturing, to expand the organised service sector, and to facilitate the transition to an upper middle income country.

Life and the livelihoods of the majority of people in Bangladesh are largely characterised by the use of the second or even the first Industrial Revolution technologies. At the same time, ironically, most people are also touched by the third Industrial Revolution through the penetration of mobile phone technology. The features of 4IR can be found in a handful of the better educated and privileged population who benefit from or contribute to its development at home or abroad. What this means is that simultaneously, technologies and people's skills, as well as their attitudes and aspirations, have to be lifted across the board in all four phases of industrial revolutions, starting from wherever the people are on this spectrum. This is where skills formation, the role of the education system and the relevance of 21st century skills come in.

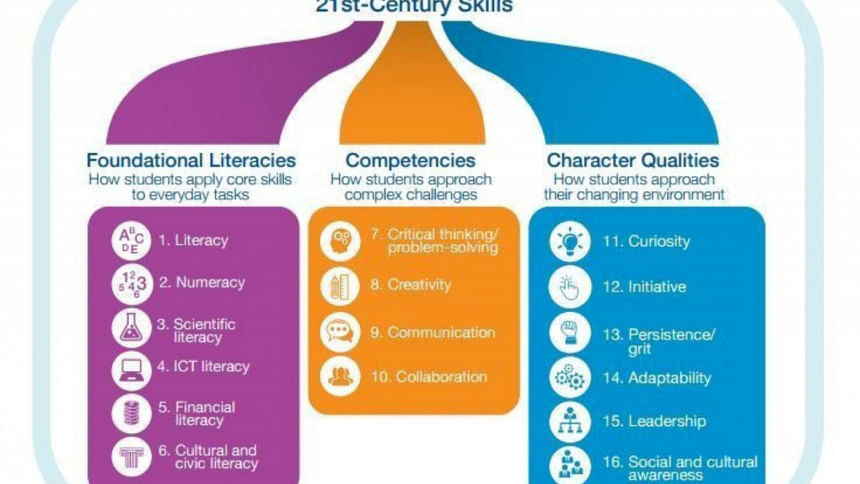

What we call 21st century skills are not necessarily all novel, nor do they mark a clean break from what were important in the 20th century or the 19th century. There are common and timeless elements of quality and relevance for learners and the whole of society in any system of education. Education systems have always struggled to achieve and maintain these essential elements, and they have not become invalid in the 21st century.

This formulation of 21st century skills recognises the value of the foundational skills of multiple literacies, the essential tools for learning. This is the base on which the higher order skills of solving problems and thinking critically are built. Young people also have to be helped with social and emotional maturity and acquiring moral and ethical values—the qualities of character. A lifelong learning approach has to be adopted for this. As in the case of technology adoption and adaptation, skills development and education also need to consider the perennial basic and essential elements that can respond to the diverse phases of technology, production, consumption, lifestyle and expectations in which people find themselves.

The education authorities—the two divisions of the Bangladesh Ministry of Education and the National Curriculum and Textbook Board—are engaged in a review of school curricula in the context of 21st century challenges. What is more important than formulating the curriculum is to find effective ways of implementing the curriculum. Teachers—their skills, professionalism and motivations—are the key here. So is the way students' learning is assessed. Look at the negative backwash effects of the current public examinations—too early and too frequent; many questions on what they actually assess; and the distortion of the teaching-learning process in schools.

A good move is to start streaming students to different tracks from 11th grade rather than 9th grade, something which is under consideration now. The aim is to build a common foundation of competencies for all, and not force young people to foreclose their life options early.

Klaus Schwab had warned that we face the danger of a job market that is increasingly segregated into "low-skill/low-pay" and "high-skill/high-pay" segments, giving rise to growing social tensions. Coping with the implications of this danger for education and skill development is a continuing concern. We cannot discuss the numerous structural and operational obstacles to necessary reforms in education and skills formation and how to deal with these within the confines of this article. But we can hardly ignore them either.

The decision-makers of today find it difficult to free themselves from the trap of traditional, linear thinking. They are too absorbed by the multiple, immediate crises knocking at their doors every day. Can they find the time and focus their mind enough to think strategically, looking at the bigger picture and with a longer time horizon, about the forces of change and disruption that are shaping our future?

Manzoor Ahmed is Professor Emeritus at Brac University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments