What Makes Good Writing Good?

To answer this question, let me hazard an analogy -- good writing is much like good food. Good writing tickles our senses the way good food does. Food habits and preferences vary across countries and continents. And, of course, different people have different taste buds to relish or resist food, which is more unique than universal. There's no such thing as universal good food. Neither is there any universal good writing. Any writing happens within the parameters of genre, audience, and purpose. Within these parameters, good writing does what it needs to do. If it needs to argue or narrate or describe, it argues or narrates or describes. What is good writing in one genre and to an audience might not be so in another genre and to a different audience. Good writing in general—if that at all exists—is not at all good. Good writing is specific, and good writing is writer specific. And that writer might be anyone in any genre—a newspaper reporter, for example.

A newspaper is potentially an excellent source of good writing, because the principles of journalistic writing hardly differ from the principles of so-called good writing. One of the basic principles of good writing is communication without discrimination. Good writing is not elitist and esoteric in nature. Good writing is egalitarian and obvious. It is engaging for and accessible to anyone who reads it either by choice or by chance. For that to happen, good writing opts for simple sentences and short paragraphs; it avoids abstractions and pretentious diction; it relies on facts and evidence rather than opinions and emotional appeals. Good writing is logical, linear, and detailed. In a piece of good writing, a reader never has to struggle to separate the agent from the action. Besides these linguistic and conceptual connections between good writing and journalism, there is also a philosophical connection between them. A principled journalist considers her work as public service, so she neither argues nor asserts. She only presents disinterested truth as a keen observer. So does a good writer. The urge to communicate, then, in an ethical fashion, makes good writing good.

We become writers by imitation as William Zinsser claims in On Writing Well. How many of us who know and care about good writing would refuse to acknowledge that the New Yorker doesn't provide adequate lessons and examples for potential writers to imitate? Some people would, because they don't generally turn to newspapers to learn and notice the quality of writing. People turn to newspapers for information on current affairs, and any discerning reader knows that newspapers manufacture and manipulate information to misguide, exaggerate, and sensationalize. Good writing in newspapers often doesn't do good, as such. Good writing, however, is invariably linked to scholarship and ethics. Journalism, as pop culture would have us believe, abandons both aspects of good writing. Consequently, journalists are misunderstood - sometimes even good ones - as 'spin doctors,' even by a scholar like Edward Said. Writing in newspapers these days evokes disbelief and indifference. Good writing presupposes engagement and savoring. This may have explained why Gabriel Márquez Garcia had to wait 20 years, until the publication of One Hundred Years of Solitude, for readers and editors to discover that one of his sailor's adventures that he ran for two weeks, each piece a day in a newspaper, was indeed good writing.

Márquez's case reveals an inconvenient truth about so-called good writing. Good writing is often regarded as not good not because of the writing itself, but for the by-line—that is, the writer. When it comes to so-called good writing, she is accessory to a crime who asks, "What's in a name?" It's all in a name. Because of rumor or recognition, once readers hear through the grapevine that someone is a good writer, that writer is idealized and appreciated. She sets the standard for emerging writers. New visions, voices, and styles in writing that don't fit in her mold fall out of publishers' and readers' favor. That's how aspiring writers are often snubbed. In order to dramatize the difficulties faced by aspiring writers, Doris Lessing, a Nobel Laurate in literature from Britain, did an experiment that she discussed in her Paris Review interview in 1988. She sent two novels to her long-time British publisher, Jonathan Cape, under a pseudonym, Jane Somers. They declined to publish the novels, because the novels were not "commercially viable" and were "depressing." Eventually, two novels in one volume, The Diaries of Jane Somers, were published both in the U.S. and the U.K, with little fanfare and few sales. She again published The Diaries of Jane Somers under her name. Readership increased; sales soared; and kudos abounded. Relishing good writing is akin to hero-worshipping.

Some heroes in writing were not initially worshipped. Herman Melville is a good example. To celebrate the 161st anniversary of Herman Melville's masterpiece, Moby Dick, Google conducted a survey of 100 authors from 54 countries in 2012, and they all named it as one of the 100 best books of all time alongside Homer's Odyssey and Dante's The Divine Comedy. When, however, it first came out (Hey, it first appeared as The Whale!) in London in 1851, readers and reviewers found nothing unique and original in it. It flopped. What else would have been the fate of a book that –among other subversive, queer, and terrifying things—featured gay marriage in the mid-19th century? Melville is one of the greatest of American novelists, and Moby Dick is arguably the most ambitious book conceived by an American writer, but the book came out well ahead of its time. Even though Moby Dick was Melville's 6th novel, he was not yet so influential as to affect and alter the readership. So-called good writing apparently combines elements of conformity and compromise. And it perishes. But writing that is indeed good transcends time and space–as Moby Dick does–because it flips the way we perceive the world. Good writing challenges–and even sometimes repulses–readers.

So, good writing disturbs! Why do people read the story of a Gregor Samsa, who wakes up one morning to find himself transformed into a monstrous cockroach in Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis? The book is already about 100 years old, but the story is yet disturbingly delightful. The story swings between amazement and absurdity, and the middle space is captured by alienation, existential anxiety, and guilt. The insect of the story–that Gregor Samsa becomes– doesn't lead readers toward entomology; it directs them toward psychology and economics and miseries. Readers find their predicaments reflected in the story. The Metamorphosis is a bizarre –yet authentic– story of the vulnerability humans are doomed to deal with across ages and times. Kafka, then, told the story of an ordinary man in an extraordinary fashion built on a solid narrative arch. The story touches and transforms. And that's exactly what good writing does. Good writing disturbs to refine and reform.

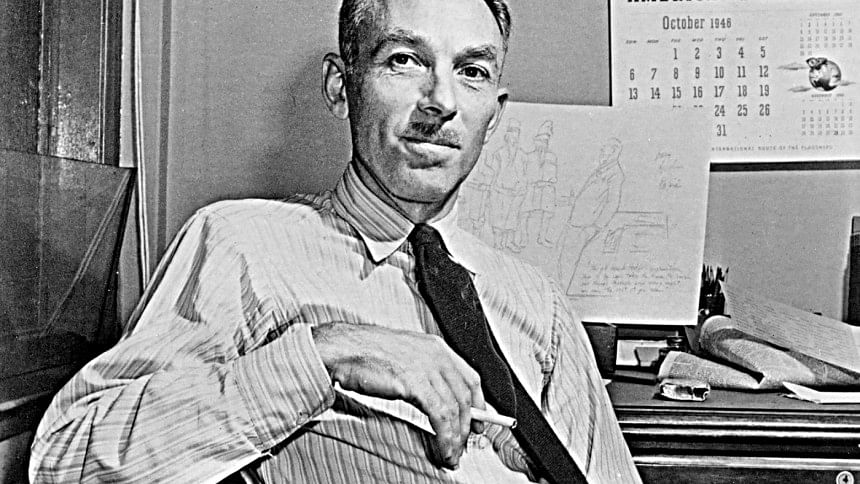

Good writing doesn't have to disturb. Good writing dispels confusion, and spurs curiosity. Good writing identifies and dramatizes the gaps, skips, and blind spots in our understanding of and interaction with the forces and factors that comprise our life. Good writing emerges out of life to enlarge it. Good writing is serious, even though it's comic. Think, for example, of George Orwell's Animal Farm. It's apparently a fairy tale told by animals; actually, though, it bemoans the loss of freedom, equity, and democracy because of betrayal and dictatorship, which was symbolic of the Stalinist era of the former Soviet Union. In his essay "Why I Write" published in 1946 Orwell wrote that Animal Farm was the first book in which he tried, with full consciousness, "to fuse political purpose and artistic purpose into one whole." What Orwell suggests here about good writing is that it is intentional, not incidental. Good writing doesn't just happen. It happens –as William Faulkner claims in his Paris Review interview–because of experience, observation, and intuition.

Rarely is it true that two people experience, observe, and intuit the world exactly alike. People have different biases and orientations shaped by different cultures and languages. Writing captures the differences and diversities that people (have to) embody across cultures and languages. Nobody, then, can lay down the rules for good writing across cultures and languages. Good writing is an expectation rather than a reality. Very few writers across languages and cultures, though, seem to know and cater that expectation to their readers. The handful of writers who do are almost always the so-called creative writers. It's always a Charles Dickens, never a Richard Dawkins. No one disputes that Charles Dickens is a good writer, but some argue (Steven Pinker in The Sense of Style, for example) that scientists are the best writers because they are the lucid expositors of very complex ideas. Richard Dawkins is a scientist (an evolutionary biologist, more precisely), who is an artist when it comes to language and communication. Because our perception and definition of good writing is restricted to so-called creative writing, an extraordinary creative non-fiction writer like Richard Dawkins–and many others like him– cuts no ice with the keepers of the "good writing" standards. Good writing, therefore, is a problematic label, which smacks of disciplinary politics and cultural conditioning as well as reader's needs and habits.

So, what makes good writing good? Discover yourself!

Mohammad Shamsuzzaman is an Assistant Professor, Department of English and Modern Languages, North South University, Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments