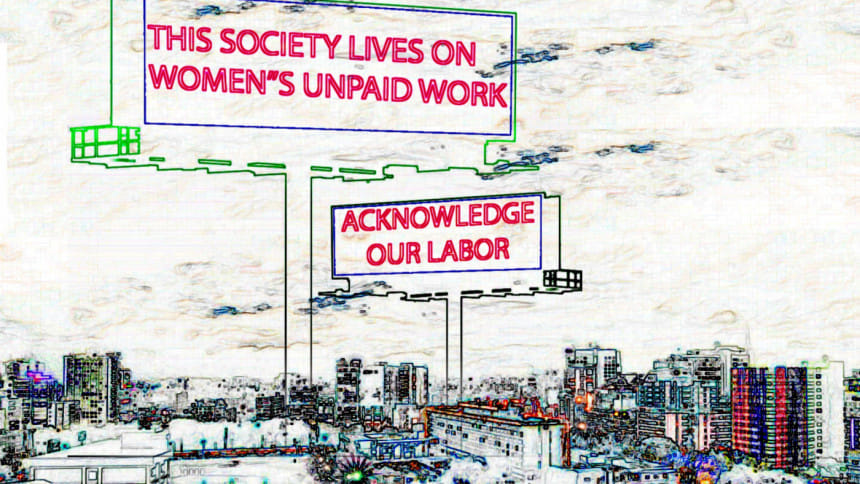

Should women alone bear the burden of unpaid work?

For Nasima Begum, a 40-year-old who works as a domestic help in the capital's Mirpur area, balancing between her paid and unpaid works has become a daily battle ever since she came to Dhaka in search of a livelihood. Hailing from a village in Barishal, she finds it extremely difficult to run her six-member family with the meagre amount she earns from working in three different households. While poverty has forced her to marry her two daughters off at an early age, she still has to feed the remaining two daughters and two sons who stay with her. Her husband, a tile fitter who often remains unemployed, hardly takes care of their 3-year-old son, let alone doing any household chores.

As I listened to her story when she came to work at our house, I was shocked to learn how little she earns after toiling from morning till night. According to her, after waking up at the break of dawn, she does the cleaning, washing and cooking for her own family. Then she has to cook for her elder brother's family (since his wife lives away in the village). And from midday till night, she works as a chhuta bua (part-time domestic help) in different households.

Even though she doesn't like to work as a domestic help and wishes to work in a garment factory instead, her responsibility at home has always been a barrier to her doing so. What is even more frustrating is that, after getting a job at a childcare centre in a garment factory for a monthly salary of Tk 12,000 recently, she couldn't join there. The authorities there did not allow her to keep her 3-year-old son at the childcare centre citing "many" problems. And since it was an eight-to-eight job, it was not possible for her to take it leaving her son at home for such a long time. The result is, she is now stuck with her old job as a domestic help, struggling to make both ends meet.

Nasima's story represents the struggle of thousands of women who come to the capital in search of a livelihood but fail to get a job being stuck between daily household chores and caring for their children, eventually being forced to work as domestic helps for minimum pay.

The vast majority of women in our villages have also never earned a single penny in their entire life, despite the fact that they are doing all the work at home and also taking part in the farming activities.

An ActionAid Bangladesh study titled "Time Use of Adult Women and Men in Rural North: Pattern and Trend", done in Gaibandha and Lalmonirhat in 2015, has found that women spend five times more time on unpaid household chores than men, which remains unrecognised both at family and national levels. Women devote an average of 6.45 hours to care work at home compared to men's average of 1.2 hours a day. As the study found, most of women's unpaid work involves cooking. And unbelievable as it may sound, a 72-year-old woman would spend 12 years of her life just on cooking.

The situation of the urban middle-class women is not any better when it comes to doing unpaid work. I personally know a number of women who, despite having obtained the highest academic degrees from reputed public universities, could not enter the job market, or in cases where they did join a job, couldn't continue with it only because there was no one in the family to take care of their children. And when it came to leaving the job for the sake of their children, it's always the women who had to make the compromise even if both partners' monthly income was more or less similar.

Strangely enough, women who overcome all these barriers to continue with their jobs still have to do the bulk of everyday chores. In cases where men share some of the work with their partners, when it comes to taking care of the children and the elderly, they hardly do anything. In addition, to balance between their jobs and care work, women often go for low-paid and part-time jobs.

According to an IMF working paper titled "Reducing and Redistributing Unpaid Work: Stronger Policies to Support Gender Equality," for women who do paid work, "occupational downgrading" is common as women choose jobs at a lower skill level or engage in part-time work to balance paid and care work. Also, "women's higher prevalence in part-time work arrangements is one of the key drivers of observed gender wage gaps, creating a feedback loop for gender inequality in unpaid work."

Research also shows that the percentage of urban women joining the workforce is less than that of rural women, and although more women are now joining the workforce, most of the jobs that they do are informal and low-paid. At a recent discussion held at The Daily Star, Fahmida Khatun, an economist and Executive Director at Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), observed, "In 1974, women's participation in the labour force was only around 4 percent. But it has now increased to around 35 percent, according to the 2016-17 Labour Force Survey. However, these women are mostly engaged in low-paid jobs and 89 percent of them are in the informal sector."

As researchers have pointed out, the reasons why it is being more difficult for urban women to join the workforce are: not having day-care centres at the workplace, an increase in nuclear families which puts the entire burden of household work on women, lack of safety in public places and public transports, as well as men's lack of willingness to share the household chores with women because these works are not compensated by wage.

As women, both urban and rural, get stuck at their homes doing everyday household chores and caring for their children, they lose their dignity and self-respect in the process. Because their unpaid work—which contributes significantly to the economy (A study by South Asian Network on Economic Modelling (Sanem) finds that if monetised, the value of women's unpaid work would be 40 percent of the GDP)—is neither valued by their family members nor by the society at large.

So it's imperative that the government formally recognises the value of women's unpaid work and their family members, particularly men, are sensitised about the issue. However, only recognition is not enough to improve women's status in family and society; the burden of unpaid work on women needs to be reduced by redistributing the work and changing the social and cultural attitude towards women's role in society.

We need stronger policies to address the specific challenges faced by women to help them enter the job market. The IMF study has come up with some policy decisions that can be considered by our government to reduce women's unaccounted work and increase their participation in the workforce.

Since social perception has a great influence on women's employment decisions, the government needs to work in that area with assistance from the private sector. The IMF study has also found that only women with higher education can substitute unpaid work with paid work to some extent, meaning that investing in girls' education is crucial. Moreover, investing in care services and reducing care burdens can potentially increase women's labour force participation, particularly in the urban areas. Also, family-friendly policies with flexible work arrangements and adequate social security services can help women join and stay in the labour force.

"Recognise, reduce and redistribute"—this can be our motto as we go about addressing women's unpaid work and increasing their participation in the workforce.

Naznin Tithi is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments