The narrative on rising inequality

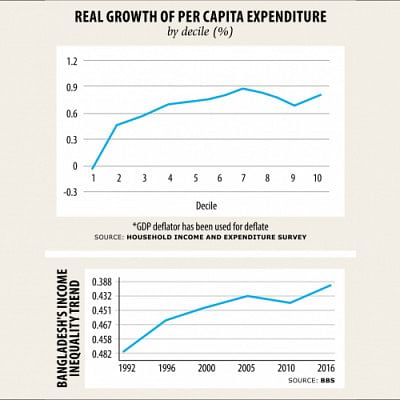

Inequality occupies a salient spot in Bangladesh's development discourse. Most measures of inequality increased from 2000 to 2016. In recent years, the income Gini coefficient increased from 0.458 in 2010 to 0.482 in 2016. The number of ultra-high net worth (above $30 million) population increased 17.3 per cent during 2012-17, according to the Wealth-X report.

What do we make of the rise in inequality?

STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATION

One explanation that seems to have gained uncritical acceptance in the establishment is the Kuznets's inverted U-Curve.

Income inequality is low at very low levels of income. Practically everybody lives at, or close to, subsistence level. As the process of growth began, people migrated from the traditional agriculture where incomes are low to modern industry, garments being the biggest but not the only one, and abroad, where wages are higher.

The scarce physical and human capital are still heavily concentrated among the relatively few. The high returns they command caused income inequality to rise. As the accumulation of the two types of capital becomes more diffused among the population, income distribution will tend to become more equal with the rise in industrial diversification, agency and the welfare state.

The rise in inequality, therefore, is a temporary phenomenon that development will self-correct. This would have been reassuring if we could safely assume inequality predominantly resulted from structural transformation.

In Bangladesh, the change in income share by deciles in 2016 compared with 2010 (the Household Income and Expenditure Survey data of the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics) depicts a combination of S-shape (poverty trap) at the bottom and elephant shape at the top, notwithstanding the fact that survey data cannot capture top incomes well and are not consistent with macroeconomic totals.

The income shares of the bottom 30 per cent declined from 9.25 per cent in 2010 to 7.95 per cent in 2016 while the share of the top 10 per cent increased from 35.85 per cent to 38.09 per cent. The share of the middle 40-60 per cent rose from 18.33 per cent to 18.85 per cent while those in the 70-90 per cent decile dropped from 36.5 per cent to 35.17 per cent.

The share of the bottom 5 per cent declined from 0.78 per cent to 0.23 per cent while that of the top 5 per cent went up from 24.6 per cent to 27.8 per cent.

Income growth rate has been the slowest at the bottom 30 per cent and negative at the bottom 5 per cent, while they have been the fastest at the top 10 decile. The middle 40-60 per cent had modest growth and the upper middle 70-90 per cent even less so. The ultra-rich enjoyed much higher income growth, which swamps that of the bottom 30 per cent. Poor still gained, but their growth was dismal compared to that of the top 10 decile.

These patterns are antithetical to the structural transformation explanation. Indeed, in the last four decades, very different pathways observed in developing and developed nations have drawn attention to the criticality of political and institutional factors in shaping the distribution dynamics.

EXTRACTIVE INSTITUTIONS

Institutional arrangements dominated by elites breed inequality. There is clear link between the two in cross-country data. The correlation between income share of the middle-income quintile and various measures of institutional quality (Worldwide Governance Indicators) are in the range of 0.3 and 0.44. Similarly, the correlation between many measures of institutional quality and the Gini coefficient ranges between 0.40 and 0.44, depending on the aggregate institutional measure used.

Governance deficits perpetuate and exacerbate avoidable inequalities. Empirical investigations find significant negative relationship between the technical and agency dimensions of governance with rising inequality.

To the extent growth is biased in favour of the owners of capital in a labour-abundant economy because of trade and exchange rate policy distortions or monopoly rents, it constitutes a technical flaw in the quality of economic governance. The failures of the agency dimension are manifest in the existence of loan defaults, tax evasion, embezzlement of public funds, socialisation of private losses, and predatory business and political behaviour. The flight of this money to safe havens abroad adds insult to injury.

Access to public institutions is heavily biased towards the wealthy. The evidence from Bangladesh glares at one's face when gleaned from various Transparency International Bangladesh reports, the Global Financial Integrity findings, the financial sector and public procurement assessments, the government's anti-corruption drive, and myriad of anecdotal stories on elite capture of trade, fiscal and financial policies.

Inequalities arising from the technical and agency failures of governance are pernicious. High-income inequality allows the rich to wield stronger political influence, thereby subverting institutions.

Weak institutions are conducive to income inequality and inequality weakens institutions.

LOW INTERGENERATIONAL MOBILITY

There is evidence that inequality in human development among children belonging to different socio-economic groups is attributable to the difficulties of overcoming circumstances inherited at birth. Such path-dependent inequalities tend not to self-correct.

Nobel laureate Amartya Sen pointed out that individuals can differ greatly in their abilities to convert the same resources into a state of 'being and doing' such as being well-nourished or having shelter. Individuals also differ in their capability to choose between different kinds of life. People can internalise the harshness of their circumstances so that they do not desire what they can never expect to achieve.

The disadvantages inherited when born into poverty is self-reinforcing. Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo explain in Poor Economics how your income today could influence what your income will be in the future. The amount of money you have today determines what you eat, how much money spent on health, education, and ways to improve your work. This in turn influences your incomes in the future. The poverty trap is an "S-shaped" curve where future income continues to be lower than present income.

This explains why social mobility is lower for impoverished people than their counterparts with a higher income. The presence of such a phenomenon at the bottom of the income distribution in Bangladesh was noted earlier.

INEQUALITY HAS DEEP ROOTS

The bottom line is that structural transformation and governance deficits create, and low intergenerational mobility perpetuates, inequalities across generations. Addressing persistent inequality requires reforms to strengthen governance institutions, efficient growth, social protection and enhance opportunities for all without discrimination.

Breaking the cycle of low mobility and high inequality will require removing the disadvantages that certain segments of society face due to their pre-determined circumstances. The focus must be on selected interventions on which a body of rigorous evidence has been accumulated. Existing evidence points to early childhood development, universal health care coverage, good-quality education, conditional cash transfers, investments in rural infrastructure, electrification and income and consumption taxes as promising areas of interventions.

The author is an economist

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments