The Women's Movement in Bangladesh Throughout the Years

Over three decades ago, in 1988, March 8 was first observed in Bangladesh as International Women's Day. The women's movement has always been deeply rooted in this society. As we move from one era to another, we can trace overarching themes of eliminating violence against women, fighting for reproductive rights, striving for political and economic empowerment, resisting religious subordination and ensuring public roles. The movement has been involved in fighting for legal rights, challenging existing discourse, increasing representation, pushing for policy changes and, most importantly, challenging mind-sets in a repressive patriarchal society. This is a glimpse into the journey across a century – one of great adversaries and greater women.

British Period

This period saw public discourse around women's rights and roles in the Bengali-Muslim society largely shaped by male perspective, including some urban educated middle-class and upper-class women. A small class of exceptions – women such as Begum Rokeya – went against the norm and became thought leaders in the women's movement. Today, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (1880-1932) is recognised as a pioneering activist for women's education and economic independence. However, what is often side-lined is her constructive and critical literary work that challenged entire systems upholding patriarchy, including religion. "Sultana's Dream," one of the earliest depictions of feminist utopia, uses the concept of gender role reversal to highlight the perceived notion of male superiority. "Secluded Women" is a critique of the extreme forms of purdah imposed on women, acting as obstacles towards their emancipation. For the first time in the region's history, feminist discourse was shaped and informed by women themselves.

During the same time period, revolutionaries like Pritilata Waddedar (1911-1932) and Kalpana Datta (1913-1995) took up arms in the nationalist struggle against British occupation. Pritilata did not only lead the successful raid of the European Club in Chattogram at just 21, but her participation in the anti-colonial struggle, along with that of several other fearless female revolutionaries, opened up political and public spheres to women.

Pakistan Period (1947-1970)

In 1970, Sufia Kamal founded Bangladesh Mahila Parishad, the country's oldest women's rights organisation to date. Ever since, the organisation has been a dominant force in shaping the roles of Bangladeshi women in politics and society.

Bangladesh Mahila Parishad is the prime example of how efforts in mobilising women led to changes in legal and political systems. Building off the momentum of the social uprising against dowry in the late 70s, they raised the Anti-Dowry Bill – with 30,000 signatures – in Parliament and finally got it passed in 1980. While the practice of dowry still persists in many places and much has to be done in the way of implementation, this was a historic win for the women's movement as they were successful in garnering support from across the political spectrum to outlaw an outdated practice.

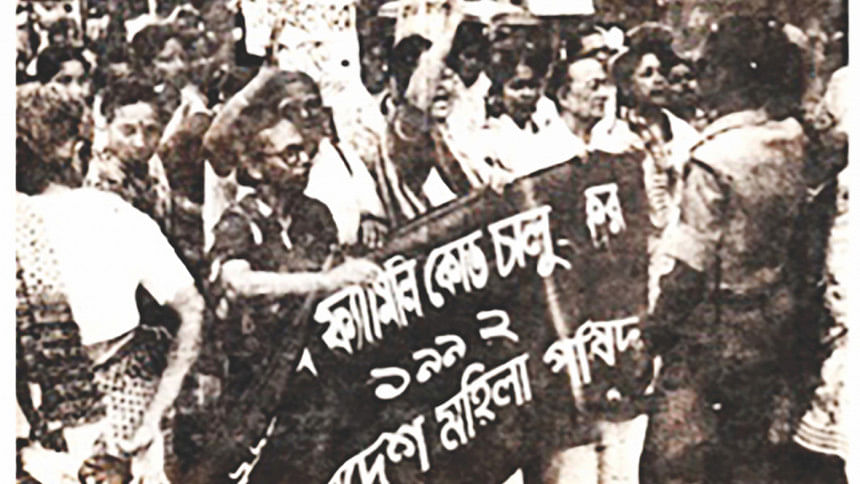

Another one of Bangladesh Mahila Parishad's major undertakings was the demand for a Uniform Family Code across all religious communities instead of personal law which depends on women's religious backgrounds. After numerous consultations at the national and local levels in the late 80s and 90s, a draft was developed. However, due to the reluctance of some religious minority groups and the state's apprehension due to perceived backlash from groups with religious affiliations, the Code was never passed.

For Bangladesh Mahila Parishad, advocacy for women's increased political participation has always been a primary agenda. By using media such as seminars and conventions alongside street activism and protests, they have continued to demand more reserved seats for women in Parliament, as well as direct election for those seats. As they stand firm in their belief that female involvement in decision-making and legislation is essential for women's empowerment, this remains a major area of their work, even today. Direct election at local levels, however, has significantly improved women's political rights and participation.

Post-Liberation (1971-1990)

Women also took up space in the policy circle, pushing for changes that addressed women's needs. The First Five-Year Plan of Bangladesh only identified the need for women's development in terms of motherhood and rehabilitation of war victims. To overcome the gap, Rounaq Jahan founded Women for Women in 1973. Known as one of the first feminist organisations focusing on research and advocacy, it published the first comprehensive report on challenges faced by women. The data and statistics required to integrate the needs of women into policy were generated; knowledge creation became a prominent tool of the women's movement.

Throughout the 70s, there was a growing consciousness of the varied experiences of women across Bangladesh. With the establishment of organisations such as Banchte Shekha (Learn How to Survive), the scope of the women's movement was expanded beyond the urban upper and middle-class.

The activism of Dr Angela Gomes, Founder and Executive Director of Banchte Shekha, grew out of her personal experiences and observations. She was raised in a small village near Dhaka. As she rode around the countryside of Jashore on a bicycle, she began interacting with fellow women, talking about the different forms of violence that they had faced. Many women were either abandoned or abused by their husbands. Through these conversations, she began to offer what little help she could. Seeing her as a threat to the traditional way of life, men in stark opposition threw rocks and human excrement at her. To legitimise her presence, she established Banchte Shekha as an NGO in 1976. Her work is rooted in the goal of helping women achieve financial independence, mimicking the ideals Begum Rokeya brought forth over half a century ago. As such, the organisation teaches rural women income-generating skills like fish farming, raising crops and livestock, and handicrafts. With their earnings, women have formed extensive networks of money-lending schemes to help others during times of crisis. Primary schooling programmes for adults, as well as courses on maternal and basic health, are also provided. Even further, the organisation trains paralegals in Muslim family law. As a result, the typical all-male mediation panels for issues such as domestic violence, dowry disputes and child support now include members of Banchte Shekha as arbitrators.

The organisation's reach today is 25,000 women in 430 villages. With Dr Gomes' acute understanding of the demographic, each programme rises out of a specific need felt by the women she works with. "The aim of Banchte Shekha," Dr Gomes said in an old interview, "is not to rescue women, but to help them learn to live."

While Bangladeshi women's issues became more and more prominent in the national landscape, there was a severe lack of representation of indigenous women's rights. In 1988, the Hill Women's Federation (HWF) was formed to help bring focus on raising consciousness among the Jumma women about their rights and duties as the most repressed section of the Jumma society in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Kalpana Chakma, the 20-year-old organising secretary of the Federation, rose to prominence because of her tireless activism and began to garner both national and international attention. She helped bring attention to an issue that still prevails in our country today: the repression of indigenous people by Bengali settlers. She put emphasis on working for the rights of indigenous women by organising conferences, seminars and meetings in several areas of the Hill Tracts. The HWF is, as Kalpana Chakma was, exceptionally vocal on the topic of Jumma women resisting repression at the hands of the Bangladesh Army, and organises protest demonstrations on all incidents of human rights violations against them. In a country where dialogue centred on the rights of indigenous people is left out of the national discourse, Kalpana Chakma helped create momentum on this journey by trying to build a more inclusive community.

My Body, My Right – 1990s

In the 1990s, a new form of organising amongst women's rights organisations – at the intersection of activism, research and advocacy – seemed to emerge. There was a focus on the physical and sexual violence experienced by women in public and private spheres.

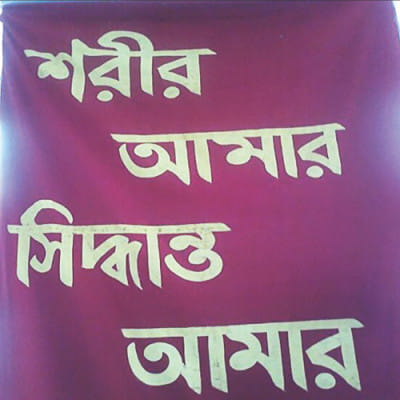

One of the more radical groups during this time was Naripokkho, a collective of women's rights activists with a mission to centre their work on their personal experiences as women. Naripokkho played a significant role in establishing the issue of violence against women as a determinant for their position in society and starting national dialogue around women's bodily rights, including sexual rights. One of their more controversial campaigns was under the theme Shorir Amar, Shiddhanto Amar (My Body, My Decision). While the aim was to strive for women's right to take decisions about their own bodies, the slogan was deemed as overly sexual or vulgar, with sexual freedom being equated with promiscuity. Today, Naripokkho has expanded their focus to issues surrounding gender and healthcare, environment, and political empowerment.

Naripokkho has also been a strong ally in the fight for sex workers' rights in Bangladesh. Following the evictions of sex workers from brothels in the late 1990s, sex workers mobilised and became more politically active in the context of the women's movement. Mumtaz Begum, an evicted sex worker from one of the brothels, contacted Naripokkho and staged a protest in front of the Press Club. This led to the formation of Ulka, an organisation that aimed to destigmatise the life and work of sex workers. Sex work in Bangladesh is often seen as a function of poverty, thus evoking the standard welfare response of rehabilitation into marriages and "respectable" occupations. Ulka's campaign questioned these "rehabilitation" prescriptions and instead raised an agenda of "social acceptance" involving recognising sex work as a legitimate occupation. After the Tanbazar eviction in 1991, Ulka and Naripokkho joined forces in order to strategise ways to bring the situation under control. Around 84 women's and human rights' organisations and development NGOs representing a wide spectrum of views on social change came together to form Shonghoti, an alliance in support of the rights of sex workers. By bringing the hardships of sex workers into the limelight, the links between the many different realities of women in and out of sex work became evident. These efforts changed how sex work was viewed in the community. A shift in terminology was observed when print media started referring to sex workers as jouno kormi, instead of potita (prostitute; literal meaning: "the fallen one"). This was a step towards removing the shame associated with sex work, and the social discrimination that was attached with it. Sex work was finally addressed as an occupation and sex workers had claims to workers' rights. The importance of sharing the stories of sex workers in order to remove the stigma surrounding this field of work was recognised. A new solidarity between sections of the "mainstream" women's movement and sex workers' struggles was forged.

A prevalent form of violence against women at the time was acid throwing. Nasreen Huq, a member of Naripokkho, founded and led a national campaign against acid violence and this, in turn, led to the formation of the Acid Survivors Foundation. Through her work, Nasreen Huq moved beyond providing survivors with medical and legal support and helped reintegrate acid survivors into society through education, employment and social interaction. In fact, her relentless advocacy actually led to a sharp fall in the number of acid attacks against women in Bangladesh.

Towards greater inclusion: 2003 and beyond

Economic Justice

This was a period of economic transition for the agriculture-dependent society of Bangladesh. More economic opportunities also created scope for labour exploitation, especially of women. Nazma Akter, Founder and Executive Director of Awaj Foundation, has been fighting to improve workers' rights in the garments sector in Bangladesh for over 32 years. Working at garments factories since the age of 11, she witnessed the abusive nature of typically male employers towards female workers. The trade unions, meant to offer solutions, were plagued with their own issues of gender-based discrimination, so she ultimately decided to form her own. Founded in 2003, Awaj Foundation is driven by the vision of decent work, dignified lives and gender equity in the industrial sectors of Bangladesh. It raises awareness on garments workers' struggles, educates them on their rights under national and international legal frameworks and builds their capacity for leadership and negotiation of better working conditions. 52 anti-harassment committees have been set up in factories in Dhaka and Chattogram divisions with their assistance. As a women-led organisation, addressing gender-based violence is one of Awaj's main priorities. Nazma Akter puts particular emphasis on increasing women's participation in decision-making at the workplace and at home. Thereby, Awaj Foundation ushered the ideals of the women's movement into a crucial sector.

Trans Rights

From an early age, Joya Sikder's experience as a transgender woman has made her vulnerable to violence and degradation. The abuse she faced was not only limited to strangers but persisted even within her own home and community. She began her activism at an NGO and continued it as a research associate seeking to depict the issues faced by the Bangladeshi transgender populace, eventually founding her own organisation, Somporker Noya Setu (SNS). Through her work, she strives to help members of the transgender community live as free citizens – providing them with work opportunities, promoting safe working conditions, actively protesting against their exclusion from a sexual rights bill on the basis of sexual "disability" and publishing articles on the abuse and harassment they face as sex workers. She played a significant role in persuading the government to recognise Hijras as a third gender. Currently, she is working on the official definition of "transgender" in Bangladesh and trying to clear misconceptions held by wider society. What started out as a fight for trans rights for Joya, has now grown to include all gender diverse and sexual identities.

The nature and scope of feminist organising in contemporary Bangladesh has changed. Organisations working on issues of gender rights are largely influenced by international donor organisations. Dependency on foreign funds means that local agendas and priorities are not given precedence, with a focus on projectised organisational models as opposed to movement building.

Bangladesh has had a rich history of feminist organising, as shown above. Throughout our history, women have recognised and prioritised the same core feminist issues of choice, autonomy, and opportunity. While this is not an exhaustive timeline by any means, it attempts to contextualise the role of the organisations and individuals within the greater feminist movement in Bangladesh. We hope the radical work of the women before us will help inspire new generations to join the fight.

The authors are members of Kotha, a youth-led organisation that tackles the culture of gender-based violence by working at the intersection of education, research, policy and the arts. They can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments