Pins and needles at the time of a pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has shaken the world's economy and has been the most pronounced public health disaster since the Spanish Flu which took place just about 100 years ago. The ready-made garment sector, along with the migrant workers, has been one of the major drivers of the socio-economic development of Bangladesh in the last 40 years. The pandemic has put the four million workers and their families between a rock and a very hard place. The closedown of all major economies has halted the retail activities there. As a result, most major buyers have either cancelled or withheld existing orders placed before the local suppliers. According to the BGMEA data, the total value of RMG export orders cancelled or suspended by global buyers has neared USD 3.15 billion till Monday, April 13, affecting 2.26 million RMG workers directly and also stifling backward linkage industries depending on the sector. On the other hand, Bangladesh is facing rising cases of COVID-19 and this has resulted in sector-wide factory closures, with no certainty when they will be reopened.

In this backdrop, BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University has undertaken a series of research studies to understand how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected different populations. One particular group of people addressed in one of our studies was RMG workers. A major research activity included a rapid survey where we reached out to respondents from different surveys that the School carried out in the past. Many of these surveys collected phone numbers of the respondents. We followed a rigorous process of obtaining informed consent over phone calls. Each call lasted on average 45 minutes.

In this article, we focus on a cohort of RMG workers who were surveyed from September to December 2018. In the original survey, there were 375 respondents, with 52 percent female and 48 percent male respondents. As a part of the rapid survey, we aimed to survey all the participants. The rapid survey started on April 5, 2020. We have successfully surveyed 159 respondents as of April 13, 2020. Coincidentally, this also overlapped with the period when confirmed cases soared exponentially in Bangladesh (for example, doubling time of confirmed cases dropped from three weeks on April 3 to three days by April 10, staying steady at the level). We wanted to understand a number of outcomes related to income, employment status, consumption, and practice and perception of different preventive measures to lower the risk of COVID-19 infection.

About 78 percent of the respondents reported living at the same place where they lived when the original baseline survey was conducted. About 44 percent reported living in Dhaka and about 30 percent reported living in Gazipur. These are the areas where most of the RMG factories are. So, at least the people we could survey were living mostly at the same place, possibly near the factories.

While many of the respondents were living at places where RMG factories mostly clustered, most of the workers faced rising unemployment and income loss because of factory closures. Ignoring the 26 respondents who did not have a job even before the pandemic outbreak, 47 percent of the workers reported complete income loss and expressed uncertainty about job continuity and future payment. However, about 24 percent of the respondents were on leave with full pay and another 11 percent were partially paid even though they were on leave at the time of the survey.

The sector-wise closure had a significant impact on households' earnings as about 46 percent reported a complete loss of income. The loss of income is partially mitigated by having multiple earners in a family, as the complete loss of income was reported by 51 percent of the households with a single earner, while it was 40 percent among the families which reported more than one earning member.

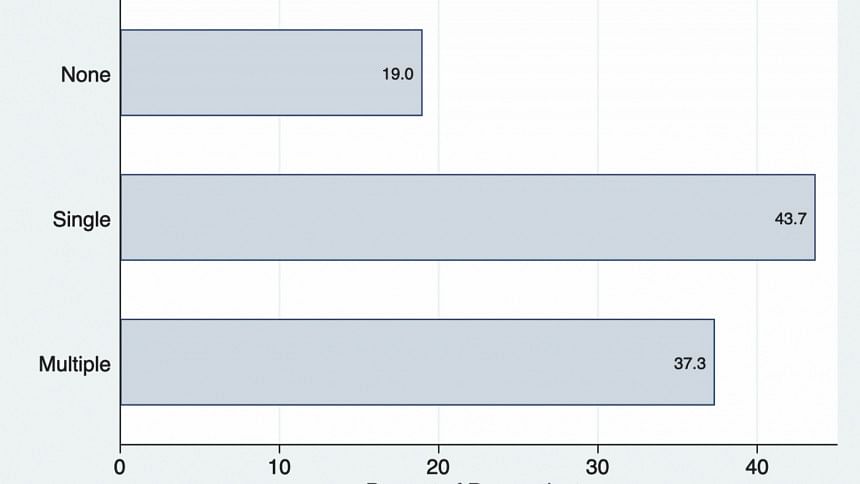

Households reported using a number of strategies to cope up with the loss of income because of the COVID-19 pandemic. About 46 percent of the respondents reported that they are now spending less to absorb the loss in income. About 52 percent reported coping up with the income loss with past savings and about 33 percent reported taking loans. These coping strategies are not mutually exclusive. As a matter of fact, as Figure 1 suggests, more than one-third of the households in our sample relied on multiple coping strategies to cope up with the income loss.

Most of the respondents, about 85 percent, reported having three meals. However, consistent with the reports of loss of income and lowering expenses, most of the respondents (87 percent) reported a decline in household food consumption. Only about 13 percent could maintain the same level of food consumption as pre-pandemic normal times.

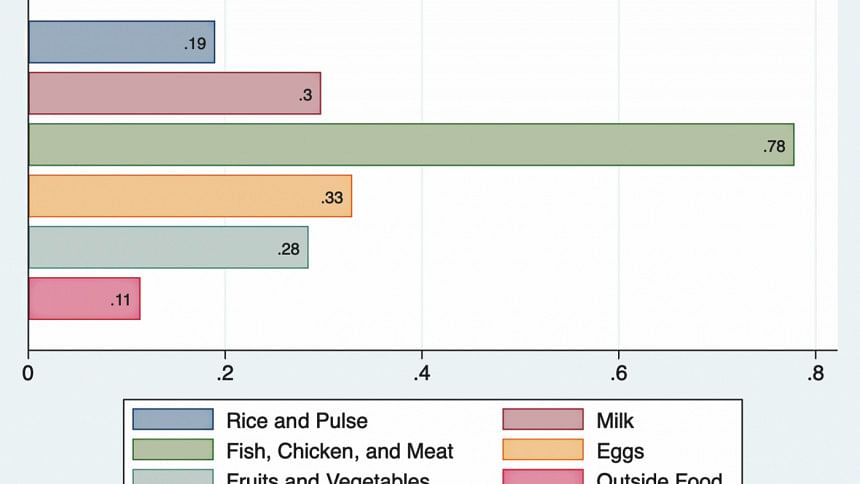

Not all categories of food items were affected adversely by the pandemic though. In particular, fish, chicken, and beef were seriously compromised because of the pandemic, as we can see in Figure 2. About 78 percent of the respondents reported that they have reduced their fish and meat consumption because of the pandemic. The other two food items also compromised were milk (30 percent) and eggs (33 percent) consumption. About 28 percent of the households also reported reducing consumption of vegetables or fruits. So, the pandemic has reduced the dietary diversity of the households significantly and, hence, they may be nutritionally compromised if the current situation continues. This will require a robust policy response in terms of food aid and cash transfer.

Among all the respondents (n = 158, i.e., not counting the missing valued ones), 49 respondents or 37 percent reported not stocking any food items nor did they want to. However, among the people who did not stock or hoard any food items (n = 141, 89 percent), 59 percent reported not being able to stock even though they wanted to. Overwhelmingly, these households reported not having enough money as the main reason for the inability to store food items in the current crisis even though they wanted to (96 percent). The households who didn't store but could store if they wanted to report having foods to sustain 13 days or about two weeks, while the households that did not store even if they wanted to report the ability to sustain seven days or just a week. So, an important policy implication will be to provide liquidity so that they can sustain more.

Most of the respondents know the value of handwashing and they think they practise it well. However, they have much less confidence in the handwashing practices of other members of the communities. Most of the respondents (60 percent) reported being able to maintain the social isolation by staying home. Among the households that could not (39 percent), the frequent need for shopping was reported as the main reason for the inability to maintain social isolation. About 88 percent of the respondents had to travel outside the home for essential shopping.

People who were not able to maintain social isolation and had to travel outside the household reported higher psychological stress . So, helping the households with money to allow a longer period of sustenance can help with both the desired social isolation and raise the mental health among the households with RMG workers.

There are two major issues here: unemployment resulting in partial or complete loss of earnings and the immediate decline in daily food consumption jeopardising nutrition security for families depending on the RMG sector.

Keeping a steady cashflow to the workers of the sector can play multiple roles. This will ensure smoothing the consumption, providing nutrition security, and maintaining aggregate demand keeping the economy from imploding.

The Government of Bangladesh (GOB) and the BGMEA have already taken up a number of measures to address these issues. Lately, the government announced a BDT 500 million stimulus package, of which the majority is earmarked for workers' wages and benefits.

The GOB has also instructed the garment owners to pay the wages by April 16, even before the employers can take advantage of the stimulus package. This will help workers and their families to maintain the liquidity until factories re-open when the pandemic weathers and demand for local supply picks up by the third quarter of the current calendar year. However, without any production, it will be hugely taxing for the employers to keep workers on the payroll.

One of the major challenges is to actually get the cash in the hand of the workers who are not attending factories anymore. Mobile financial services (MFS) can be very effective here. However, though increasing, the adaptation rate of digital wage payment among the garments factories is still low. As of November 2019, only 1.5 million workers were brought under this mode of payment. Moreover, a large part of the workers still do not own their own mobile wallets. Addressing this bottleneck will require serious logistical maneuvering.

Another potential option is a mixed support package that includes wage and financial support distribution with partial food support. The immediate food support will help them meet the present food demand and the financial support will ultimately cushion them from any deficit in food consumption as a result of the further extension of the lockdown. In addition, it will discourage any possible congregation in the markets, which is to be avoided in the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic. Still there are a number of caveats for such measures. Considering food support, the chances of leakage are higher and the distribution needs to be well-monitored by the factories themselves.

Another issue is the safety measures adopted by the factory owners. Once the outbreak starts receding and, albeit slowly, economic activities resume, the workers will still require assurance from the industry that their safety is one of the prime concerns. Thus the factories themselves need to take measures against any possible resurgence of such ailment among the workers. Such resurgences are now observed in China, and Bangladesh will need to learn from that.

Despite all these measures taken, concerns still loom, as extension of enforced measures like "social distancing" and "lockdown" is expected to have a far-reaching impact on the poor and low-wage earners. The government, the RMG industry and policy makers must weigh the risks in order to come to an informed decision. The workers are essentially the backbone of the RMG sector. Ensuring their workplace safety and economic sustainability during a crisis as such should be the main priority not only for the factory owners but also for the government itself. The RMG sector, which has been considered as the fuel driving the economy of Bangladesh for the past couple of decades, can eventually turn into its Achilles heel without timely adaptation of precautionary measures.

This article has been authored by Atonu Rabbani, Farzana Misha and Amina Amin on behalf of the BRAC JPGSPH Rapid Survey Team. Atonu Rabbani, PhD, is Associate Professor, Department of Economics, University of Dhaka, and Associate Scientist, BRAC JPGSPH, BRAC University. Farzana Misha is Research Coordinator, BRAC JPGSPH. Amina Amin is Research Assistant, BRAC JPGSPH.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments