Blocking media access during Covid-19

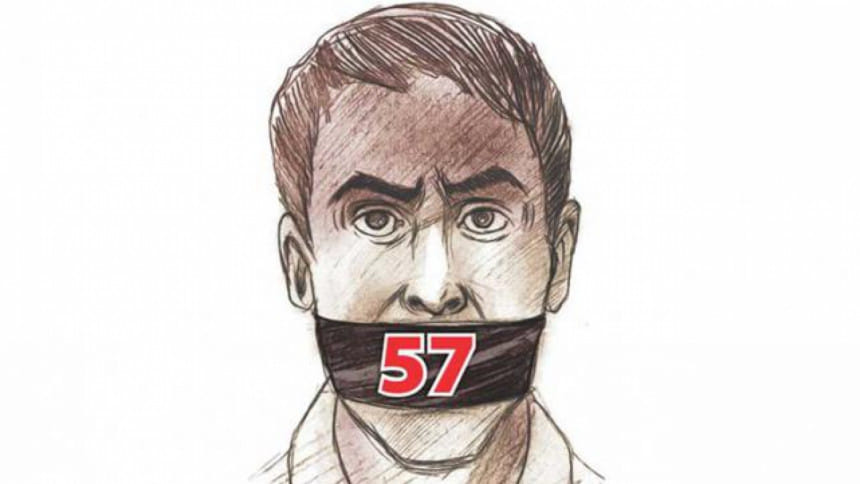

Press freedom in Bangladesh has been in decline long before the coronavirus came to our shores. Over the last decade, thanks to increasingly repressive media laws and highhanded measures adopted by the authorities, the health of journalism has been deteriorating in such a way that even the stalwarts of the fourth estate began to worry if the damage could ever be reversed. Yet, an outcome few would have expected during the Covid-19 crisis—which was expected to unite the people and their leaders against humanity's most dreaded enemy in decades—is the tightening of the noose around free flow of information, which holds the key to this unity. It's a self-defeating strategy that hurts not only the general people and the media, but those tightening the noose as well.

There are plenty of cases to illustrate this point. Take, for instance, the restrictions put in the way of journalists covering daily briefings from the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS). A report by Prothom Alo on April 30 charted the changes in the DGHS' media engagement policy that show how the government has been restricting access to information about the coronavirus. First, the journalists were robbed of the opportunity to ask questions when, on April 8, the online media briefings were repackaged as "daily health bulletins". It is common knowledge that questions are an essential part of any press briefing. They help journalists glean necessary information, challenge statements and demand clarifications if need be. But these so-called live "bulletins", conducted by a top health official, basically offer a bland, pre-scripted communiqué that demands blind faith on the part of the audience, without any recourse to verification. Then, starting April 11, information on the government's stock of testing kits was airbrushed from the bulletins. From April 24 onwards, information on daily sample collection in each testing laboratory in the country (there are 31 now) was also removed.

Could these be mere acts of omission? Should we take the statements from the administration—which has been roundly criticised for its failure to expand testing, ensure adequate safety gear for all frontline health workers, check irregularities in relief distribution, enforce social distancing regulations so essential to "flatten the curve" of the virus, and to protect the most vulnerable groups in society—at face value? Should we keep our faith in another BTV-like partisan tool of communication?

That certainly seems to be the conclusion of the administration. There is no denying that the coronavirus has created an unprecedented situation in Bangladesh as in many other countries. There is no exit strategy good enough for a crisis of this magnitude. It's also true that the virus is as much a public relations issue as a medical one, given how public perception/response can dramatically change a situation. Manufacturing approval is thus vital to the continuity of the government's efforts. We have ministers who keep telling us how Bangladesh has fared better than the likes of the US, Italy and Spain. However, such optimistic but grossly misleading claims belie the fact that Bangladesh lags far behind even its neighbours in dealing with the crisis. There are growing fears that the actual numbers of infection cases and deaths are much higher than the figures released by the authorities. The fumbling response of the authorities has justifiably made the country a case study in what not to do in a pandemic.

The list of things going haywire is quite stupefying, as a cursory glance through any newspaper will reveal. For the media and free speech activists, this essentially meant suppression of vital information, tightening of control of the social media, efforts of the administration to impose its version of journalism, threats of lawsuits, arrests and imprisonment for those speaking out about the crisis, etc.

On April 18, four journalists including bdnews24.com Editor-in-Chief Toufique Imrose Khalidi and jagonews24.com acting editor Mohiuddin Sarker were sued under the Digital Security Act for reporting on alleged embezzlement of aid for coronavirus victims in Thakurgaon's Baliadangi Upazila. They were charged with publishing "offensive, false, defamatory or fear-inducing data or information," following a complaint filed by a ruling party leader. One of the accused, local journalistTanvir Hasan, claimed that the lawsuit was filed to stifle journalists so that they do not report on corruption committed by ruling party politicians. "Police have acted swiftly in taking on the case. It's an attempt to stop us from writing about corruption," he told the Deutsche Welle (DW).

Since mid-March, according to the Human Rights Watch, the authorities have targeted or arrested a number of individuals including doctors, academics, students and opposition activists for their comments about the coronavirus, most of them under the draconian Digital Security Act. All this adds up to a grave warning: there is a systematic effort in place to silence those who express concerns about the government's handling of the crisis. Often this is done in the name of preventing the spread of "rumours" and "misinformation". As if to bolster theinformation suppression claims, on April 23, Health Minister Zahid Maleque directed officials not to talk to the media, since it "creates misunderstanding" and "it is against the government's policy." He said this while speaking at the daily online "bulletin".

True, the government has a responsibility to prevent the spread of misinformation about Covid-19. But this doesn't mean it can or should silence those with genuine concerns or criticism of its handling of the situation. According to Brad Adams, Asia director at the Human Rights Watch, "the government should stop abusing free speech and start building trust by ensuring that people are properly informed about plans for prevention, containment, and cure as it battles the virus."

Regardless of the circumstances created by Covid-19, Bangladesh's struggle with press freedom has been a constant challenge. In this year's World Press Freedom Index released by the Reporters Without Borders later last month, the country has ranked 151st out of 180 countries, while its position was 150th last year. It is instructional to take a look at these figures as they remind us how far down the rabbit hole have we fallen. Clearly, the problem hasn't been exacerbated by the coronavirus, but suppression of information and press freedom poses a greater challenge now as it has very real health consequences. This much should be obvious to anyone who cares for their life and that of their loved ones. This goes for those in power as well.

And this is precisely why journalism is more vital now than ever before. The Covid-19 pandemic has placed independent media front and centre in providing reliable, fact-checked and potentially life-saving information. An independent press can ensure our leaders and officials remain accountable and their measures are scrutinised. This will only help improve the government's response to the crisis—as will an emboldened citizenry free to voice their legitimate concerns and grievances. The opposite of it, as they say, is "pure, unadulterated chaos".

Badiuzzaman Bay is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star. Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments