A tribute to Satyajit Ray's film-making techniques

Some say there are two shortcuts to a Bengali's heart: Tagore's songs and Ray's cinemas. Satyajit Ray has made his way into our hearts during our very childhood through his books. The stories of Feluda and Professor Shangku remain fresh in our memories till this day. Ray's talents have many angles; he was a brilliant writer, a splendid artist and a filmmaker who was way ahead of his time. The depth of his understanding and knowledge of music was evident in how beautifully he structured the music in films. His debut film, Pather Panchali (1955) changed the perception of Bengali films in the international arena. The "Apu Trilogy", along with his other works of literary adaptations, among which the most prominent would be Charulata, are considered as the finest of Bengali cinemas, in terms of scripting, making, forms, techniques, and the language of the film.

Ray made Pather Panchali at a time when the industry used to follow a straight-up Hollywood approach in making films, almost all of which turned out to be mimicries of the worst of Hollywood movies. Shooting an entire full-length film outdoor with the pieces of equipment available in the early 50s was out of the question, yet he dared to shoot his first film outdoor, that too in the rural Bengal. And it turned out to be something that the industry never saw before.

Ray believed that like any other art form, cinema has a language of its own, distinct from that of literature and theatre or the other art forms. He used the various technicalities of filmmaking to express this language to the fullest. His preference for using lights and shadows in various angles to dramatise certain situations in the story was evident from his very first film. Exploring the appropriate use of different types of shots, close shots, pan shots, long shots to frame the flow of events in a lyrical manner with the limited technology available at that time was his speciality. In an interview with James Blue of Film Comment, he said, "I have the whole thing in my head at all times. The whole sweep of the film. I know what it's going to look like when cut. I'm absolutely sure of that, and so I don't cover the scene from every possible angle—close, medium, long. There's hardly anything left on the cutting-room floor after the cutting. It's all cut in the camera."

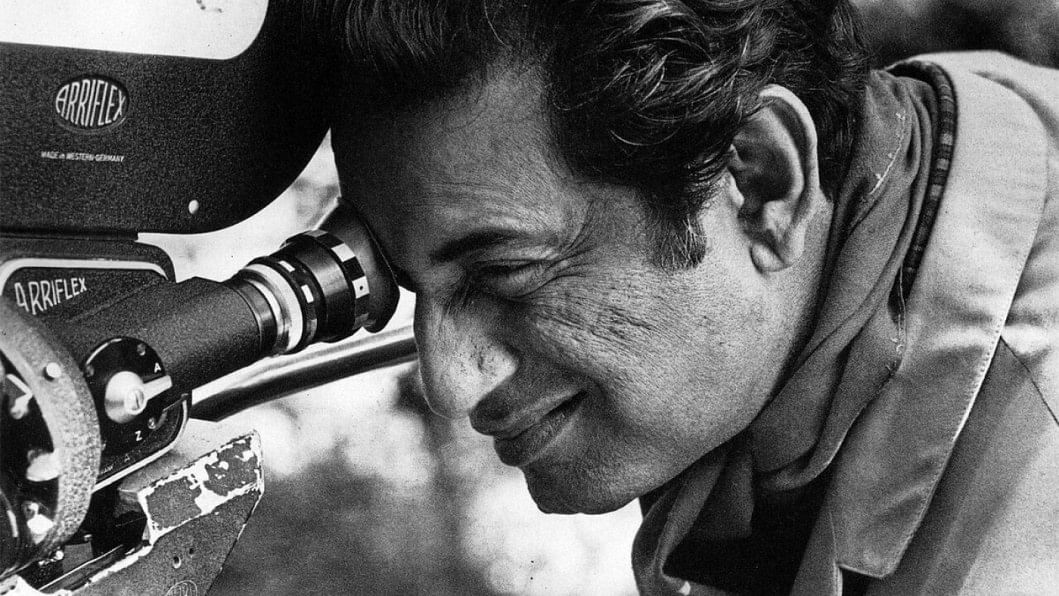

Being the devoted filmmaker that he was, he left no stones unturned to make the best use of his technical knowledge of films to tell the story exactly the way he wanted to. He spent a lot of time behind the camera, to perfect each and every angle of the shots. "Ever since Mahanagar, which I shot in 1962, 1963, I have been operating the camera. All the shots, everything. It's wonderful to direct through the Arriflex because that's the only position to tell you where the actors are, in exact relations to each other. Sitting by or standing by is no good for a director", he said during the interview with Film Comment. "I find it easier because the actors are not conscious of me watching because I'm behind the lens. I'm behind the viewer and with a black cloth over my head, so I'm almost not there, you see. I find it easier because they're freer, and particularly if you're using a zoom. I am doing things with the zoom constantly, improvising constantly."

Apart from the technical aspects of cinematography and editing, he put a lot of effort into developing the screenplays of the films that he made. He designed the title sequences for the opening credits, designed the posters and composed the music for his films. Ray had a profound knowledge of traditional classical and western music and used this understanding to serve the purpose of the storytelling better. He incorporated techniques and symbolism into the process of filmmaking without breaking away from the art of storytelling itself.

As a filmmaker who was well ahead of his time, it was quite difficult for him to make the masses understand the purpose of the films he made. People needed to be made understood about the film as an art form, he believed only then the purpose of his films would be fully served. He wrote about films every now and then, with this objective in mind. Ray's cinemas and his writings on cinemas only prove that he genuinely was the master of the art and crafts of filmmaking. He remains an inspiration for filmmakers and enthusiasts in the subcontinent till this day. We remember this maestro with utmost admiration on the occasion of his 99th birth anniversary.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments