The newly urban woman in Mrinal Sen's cinema

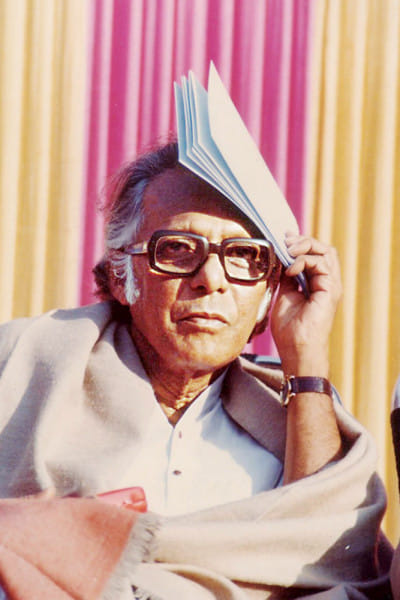

For the legendary Bengali auteur Mrinal Sen, cinema often went hand in hand with agitprop, meaning the use of political messaging as an aesthetic element. This, along with the frequent use of mid-film disruption, is one of the many techniques Sen borrows from Brechtian theatre theory. A self-proclaimed "private" Marxist, Sen was transparent about his use of cinema to expand the socialist cultural project and to bring about change. Therefore, it is no surprise that his cinema also had a lot to say about the struggle for gender equality in Bengal.

The milieu in which Mrinal Sen was making films was one of change. Much like the Neu Frau (New Woman) in interwar Germany, Bengali society demanded a reimagination of the urban woman. It was a time when Kolkata, like many post-colonial cities in the region, was embracing the idea of an independent woman outside of their domestic value. The films of that time, including popular cinema, saw a departure from the stereotypical characters of mother, wife, sister, daughter and lover.

However, reimagining the urban woman through popular cinema had its limitations. Romantic melodramas of the famed Uttam-Suchitra on-screen pairings, for example, recreated the urban woman within patriarchy, not outside of it. These films would take up a reformist approach to oppression and focus on how women's love and care have the power to heal patriarchy and society at large.

Sen's films were always resistant to the commercial cinema, and he is known to have rarely consumed any of it. His depiction of women in his films was also antithetical to these tropes of the "reformist lover" in popular cinema. Sen was concerned with the urban middle class and their complicities in keeping up with the status quo, which is inclusive of patriarchy. Be it the neo-realist dramas or the experimental features, Sen utilised every opportunity to make a poignant commentary on the apathy and double standards of middle-class morality.

In several of Sen's films, the anxiety towards the increasingly independent, and somewhat sexually positive, urbane Bengali woman is often crucial to the diegesis. When it comes to the various political uprisings of the 60s and 70s, women's liberation within these movements was still marginalised.

This is evident in Sen's 1973 film Padatik (The Guerilla Fighter), where the urban woman is represented by Mrs. Shila Mitra (Simi Garewal). Padatik centres around a Naxalite political activist, Sumit (Dhriitiman Chatterjee), who takes refuge in the wealthy Mrs. Mitra's apartment in an upscale neighbourhood. When arriving at this location for the first time, Sumit, almost mimicking the audience's inkling, asks, "She lives alone? How come there is no Mr. Mitra?"

Mrs. Mitra is a successful advertising executive who lives in a posh apartment in an upscale neighbourhood. Yet, her single status makes people uneasy. Despite her socio-economic privilege, gender roles do not escape her. This is best understood by looking at how she participates in the political movement within the film. Although she is a woman with agency, a thinking being of her own, her participation in the revolution is limited to domesticated services: providing care, refuge, and companionship for the male militant.

The following excerpt supports this claim. Former Naxalite Krishna Bandhopadhay wrote in her essay titled "Naxalbari: A Feminist Perspective" in the Economic & Political Weekly:

"We were asked to offer shelter to revolutionaries, give them tea, and carry letters and documents from one place to another. And we had one more responsibility. This was to undergo training as nurses, so that we could tend to our injured male comrades and nurse them back to health. Thanks to our care, the party could regain its comrades because the police would not usually suspect a woman. We began to feel very insignificant."

Mrinal Sen repeatedly makes a case in Padatik that the gendered categorisation of Simi Garewal's character has been internalised by the very people fighting for social change. He does so by contrasting scenes of Mrs. Mitra's domesticated service with that of Sumit's inner monologue containing strong political thought and analyses. The two days that Sumit lived alone, he was perfectly fine to fend for himself, but ever since the homeowner returned, the brunt of the kitchen work was no longer shared by Sumit. An exhausted Mrs. Mitra returns from office to greet Sumit lazily reading Maoist literature – yet she is the one who offers, "Do you want some tea?"

Here, Mrs. Mitra takes the form of the virgin Madonna – Jesus's mother in Christian theology. Mrs. Mitra's role as a care-giving patron embodies the motherly, chaste heroine that has been typecast in traditional Bengali, and Indian, literature and cinema. Her respectability comes from the fact that she is incorruptible, which makes her a trusted confidante of the movement.

This idea that women's importance pertains to the role of a caregiver is reiterated in the scene where Sumit and Mrs. Mitra are chatting at the breakfast table after Mrs. Mitra had been out late for an office party the night before. With a solemn stare, Mrs. Mitra sighs that Sumit missed last night's dinner – possibly because she was absent to prepare it for him. The director does not conclude this conversation but leaves it with Sumit blankly staring back at Mrs. Mitra. The audience is not privy to Sumit's internal thoughts and emotions but the lingering freeze-frame of Sumit's stoic, dignified stare proposes a moment of reflection for the audience. Is he angry that she didn't prepare dinner? Or did she prepare dinner, but Sumit did not want to eat without her? Is he getting emotionally attached to his patron?

In the visual language in Padatik, if love existed, it would do so only in the assumptions one makes – in the empty glances shared between Sumit and Mrs. Mitra, the hints of intoxicated nights, and quiet exchange of personal tragedies. If there were ever a connection, it would be up to the audience to assume that the glances were romantic, and the inebriated night led to romance, or the outpour of one's emotion meant anything more than a spiritual connection with a dear friend. It is up to us, the audience, to decide. Do we accuse these two characters of being anything more than roommates? Why should the relationship between Sumit and Mrs. Mitra be anything more than what meets the eye?

At the crux of the film, as Sumit battles his own political compass and begins questioning his party's leadership, other members begin to alienate him. They accuse him of lacking integrity. Part of this accusation is that he is having an affair with the patron Mrs. Mitra. Here, the film positions Mrs. Mitra as a "whore" – not in the literal sense but more in the psychoanalytical sense. The whore, too, refers to the biblical understanding of Mary Magdalene, an alleged prostitute, who was considered unholy. In the context of cinema, the Madonna and "whore" represent the dichotomy between sacred and secular under the male gaze. While the chaste Madonna is considered virtuous, the sexual "whore" is considered a woman of transgressive positionality under patriarchy.

The Madonna-whore complex in popular cinema can be commonly found in the films of Martin Scorsese and Alfred Hitchcock, amongst others. Taxi Driver and Vertigo respectively explore conflicts between perceived purity and the libidinal desires towards women.

What is unique about Sen's treatment of the Madonna-whore complex is that he approaches it as a duality instead of a binary. Resisting to position the two forces against each other, he inhibits both the Madonna and the whore in the singular character of Mrs. Mitra. This brings to light the dialectical act of creating a Bengali Neu Frau (New Woman) – free of man's jurisdiction but controlled by man's desire.

While Mrs. Mitra has carved herself an identity, she is still not free of slut-shaming, gossip, and character assassination. This is pronounced in the scene with the late-night phone call where Mrs. Mitra's ex-husband harasses her and tries to blackmail her for money. Mrs. Mitra resists the abuse, and the conversation ends in a shouting match, while Sumit overhears this from his room. The ex-husband's harassment reminds us of the perils of gender-based abuse that women are often faced with when they start to accomplish more than their partners.

However, we must note that Sen's depiction of the marginalisation experienced by a bourgeois woman is in no way a plea for sympathy towards the privileged class. It's quite the opposite. This film asks us to consider how economic privilege within capitalist societies fails to achieve a complete feminist utopia. This stance is made clear in the segment in the film where Simi Garewal's character interviews several women about their views on feminism and gender equality. Most of the respondents are middle to upper class, liberated women. However, in their testimonials, there's unanimous agreement that gender equality has not been realised in full capacity within the urban Bengali society.

"We are doing everything that a man can do, but even still, total freedom is not here because when we earn or travel, we are still doing so with the consent of men," shares one of the women interviewed by Mrs. Mitra.

In the aforementioned sequence, one of the respondents cites Henrik Ibsen's play, Dollhouse, where we see one of the early emergences of the Neu Frau (New Woman) in literature. Ibsen's material was often a source of inspiration for Sen, who openly admired the Norwegian playwright in multiple interviews. Sen's reference to Ibsen's Neu Frau underlines his self- knowledge that he, too, was constructing his own interpretation of the modern Calcutta woman.

Similarly, in Ek Din Pratidin (And Quiet Rolls the Dawn), Sen finds the new Calcutta woman in the lead protagonist Chinu (Mamata Shankar). The story centres around a middle-class family where the eldest daughter, the bread-earner of the family, goes missing. Chinu, the daughter, is an intelligent, working woman who fails to return home one day. Naturally, the family is concerned, but they remain quiet for the sake of hiding the embarrassment from their neighbours.

In the middle of the night, Chinu's brother, along with a friend, sets out to search for her. While going to the police station, he wonders out loud to his friend, "What if she got involved with something shady?" The friend talks some sense back to the brother, "What do you mean? Do you not trust your sister?"

However, upon reaching the police station, the duo is greeted by the sight of a man arrested with his mistress. The visual insinuation is obvious. In Ek Din Pratidin, the whore-isation of the female protagonist is much more spelled out than in Padatik. In signature Mrinal Sen style, a mid-scene jump cut takes us to a view of the city, dark at night. News headline flashes as text on the screen. "Female corpse floating in the lake." "Call girl confesses at court." "Record trade of women's meat." The juxtaposition of these realities with the growing suspicion harboured by Chinu's neighbours proposes an active marginalisation of issues related to sex workers' rights, gender-based violence, and sex trafficking. If it is so easy to make a "whore" out of women and push them away because of that, how does a society come together to tackle problems experienced by actual sex workers?

As the night proceeds, we see Chinu's character is measured and evaluated by her family members. The neighbours begin gossiping, although they have known this family for a long time and have respected Chinu for pulling her family through hardships. At one point, the landlord hints at the possibility of eviction. Nobody wants tenants with "loose morals." Sen paces us through the highs and lows of the night. Is she having an affair with an older man, perhaps her boss? Is she a prostitute? Does she have a boyfriend she is sleeping with? Sen shows us that it does not take a lot to think about the worst of women. Was Chinu killed in an accident? Maybe better that than all the other possibilities.

When Chinu finally returns, her whereabouts are never disclosed. Mrinal Sen has always reserved the pleasure of making his audience uncomfortable. He deliberately manufactured endings that move the audience into action. By not satisfying our curiosity about Chinu's disappearance, Sen implicates us in the act of moral duplicity. We are just like Chinu's neighbours, itching to know where she had been the night before. The family members don't probe further. Chinu's economic value to the household overrides her social transgression.

What Ek Din Pratidin has shown us, again, is that women are categorised either as chaste or corrupted – meaning their worth is entirely dependent on their sexuality. These binaries of the virgin Madonna and the whore in Sen's film problematise the idea of the Bengali Neu Frau. While the post-partition cosmopolitans saw many more opportunities for women to get an education and work, these still functioned within patriarchal modernity. For someone as respected as Mrs. Mitra or Chinu, all it took were a few rumours to question their credibility. A woman's right to sexuality and privacy is still linked to men's proprietorship. Therefore, the thought that women can act out of their sexual limits (mostly as wives) is considered a dishonour for the family.

Sen's exploration of the Madonna-whore complex was later expanded, much more ardently and aggressively, in the films of one of his frequent cast members, Aparna Sen. Films such as Paromitar Ek Din, Parama, and Goynar Baksho, among others, tackle this duality between men's desire for women to be sexual but celibate beings at the same time. Aparna Sen's work builds on the female gaze and approaches the paradox of middle-class morality with introspection.

What fascinates me about the feminist reading of Sen's cinema is how much of the bourgeois feminism critiqued in it still persists today. The last decade has witnessed a rise of "Lean In" feminism, which pushes for gender equality in the corporate world – but ignores the greater inequality created by the corporate world. "Lean In" feminism is a version of bourgeois feminism, which could also take other forms such as white feminism, eco-feminism, savarna feminism, etc. The issue with this faction of privileged gender-equality movement is that it betrays the original essence of radical feminism – equality for all. Feminism for the working class, for the landless, for sex workers, for the non-binary or trans folks, is lost with bourgeois feminism.

As Sen illustrated in Padatik and Ek Din Pratidin with his corporate-successful female leads, economic mobility for women will not dismantle patriarchy. In fact, that's not what corporate gender-equality is set out to do at all. To achieve true gender equality, a complete overhaul of the social system is necessary. As one of the women being interviewed by Mrs. Mitra in Padatik says, "If the social structure is not changed, the freedom of women is doubtful."

Sarah Nafisa Shahid is a film critic and translator based in Toronto, Canada. Her works have also appeared in NOW magazine, Hyperallergic, Wear Your Voice, and The Daily Star. She tweets @I_Own_The_Sky

References

Bandyopadhyay, Krishna. "Naxalbari Politics: A Feminist Narrative." Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 43, no. 14, 2008, pp. 52-59.

Bhattacharya, Malini. "Culture." The Changing Status of Women in West Bengal, 1970-2000: The Challenge Ahead, edited by Jasodhara Bagchi, SAGE, 2004, pp. 101-102.

Nag, Dulali. "Love in the Time of Nationalism: Bengali Popular Films from 1950s." Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 33, no. 14, 1998, pp. 779-787.

Roy, Srila. "Gendering the Revolution." Remembering Revolution: Gender, Violence, and Subjectivity in India's Naxalbari Movement, Oxford University Press, 2012, chp. 3.

Comments