Exports: riding the waves of uncertainty

In the wake of Covid-19 spreading in Europe and the US, global trade descended into a free-fall.

Bangladesh's export in March 2020—the first month to take the hit—was $2.73 billion, down by 18 per cent year-on-year.

Then came the most devastating blow in April when the figure decreased 84 per cent year-on-year to $520 million.

Things improved slightly in May, but the export receipt of $1.6 billion was still 62 per cent lower than that of the same month a year ago.

It is almost inevitable that shipments in June will also register a negative growth.

While Covid-19 has made the situation an extreme one, 2019-20 was already an unusual year for Bangladesh.

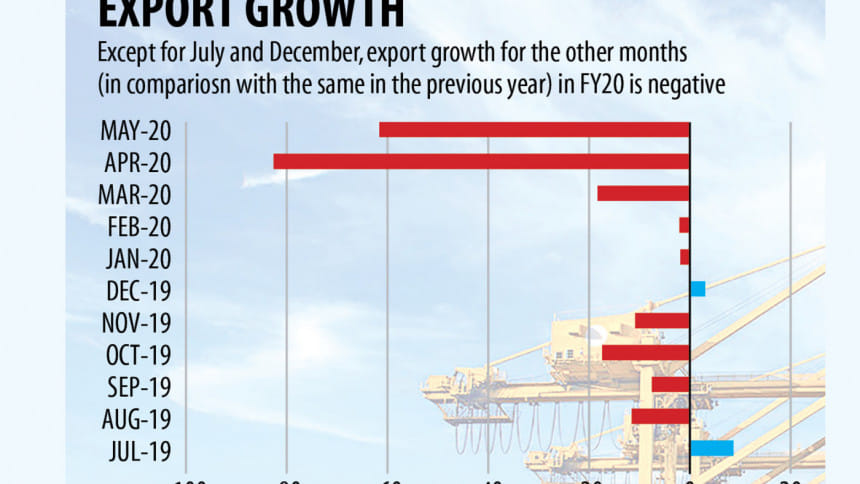

In the eight months to February this year, export earnings on six occasions were lower than those of the corresponding months in the previous year.

That is, except for July and December, export growth for 10 months in the outgoing fiscal year will be negative.

For many years, our export success had defied overwhelming odds. Bangladesh has repeatedly been shown performing worse than its competitors in various global surveys considered to be the determinants of competitiveness and trade performance.

Furthermore, vulnerability associated with excessive dependence on readymade garments has regularly dominated policy discussions and newspaper headlines.

Yet, in the most recent past decade of 2008-18, Bangladesh achieved the second highest (after Vietnam) average annual export growth amongst the global economies.

Bangladesh's wheel of fortune has now apparently taken a dramatic turn for the worse exacerbated by the global pandemic.

While most global economies have seen their exports plummeting in April and May, Bangladesh looks more vulnerable given its extremely concentrated export basket in which the share of clothing alone is about 84 per cent.

A recent study jointly undertaken by the Policy Research Institute (PRI) and London-based Overseas Development Institute shows that Covid-19 induced recessions in Western countries would lead to an 8-per cent drop in the demand for Bangladesh's exports.

This does not include other factors such as supply-side disruptions, reduced travel and tourism activities, and low consumer confidence that also adversely affects the demand.

McKinsey, a global management consultancy firm, anticipates 40 per cent of European and US consumers would reduce household spending, but a much higher proportion of 60 per cent would cut back spending on clothing and footwear.

Many analysts expect an inverted J-curve in consumer spending in the short term – a very short-lived increase in spending as people leave lockdown, but then a decline of longer duration.

Overall, a 27-30 per cent decrease in the combined demand for apparel and footwear is anticipated.

This economic downturn thus could have a disproportionately larger impact on Bangladesh's exports.

The emerging evidence seems to suggest new orders from the largest buyers (global chains and brands) to be about 30 per cent of the 'normal' level.

Retailers in the importing countries are trying to get rid of unsold spring/summer stock in markets with less seasonal differentiation.

It is now almost inevitable that the garment sector in Bangladesh will undergo significant consolidation and many smaller firms will disappear.

Many analysts and officials in the policy circle held strong views about Bangladesh's having low labour-cost advantage.

They argued that lower-income consumers in the developed countries are dependent on low-priced Bangladeshi products for which there are no alternative suppliers.

However, the notion of comparative advantage based on the labour cost alone has fast changed due to technological progress and automation.

Indeed, rival firms in China, Vietnam and Cambodia have adopted technologies to replace labour at a faster pace than their counterparts in Bangladesh.

For every million-dollar garment export, 142 workers are employed in Bangladesh, which is 48 in both Vietnam and China and 75 in Cambodia.

Foreign direct investment-led garment manufacturing in these countries has thus resulted in deepening of automation to put pressure on traditional labour-dependent production processes.

While Bangladeshi garment exporters have been complaining about buyers' offering unfair prices, the fact of the matter is technological progress has made bulk production elsewhere possible in competitive prices.

In the above backdrop, the potential loss of duty-free market access because of Bangladesh's graduation to a developing nation constitutes a cause for serious concern.

Such market access is a critical source of competitive advantage, particularly in the EU, which buys almost 60 per cent of Bangladesh's apparels at zero tariffs while most other suppliers must pay 9-12 per cent tariffs.

Given the existing EU provisions, Bangladesh will not qualify for any tariff concessions after its graduation followed by a three-year transition period.

Unless some fundamental changes are introduced, Bangladeshi exporters will see tariff hikes on their exports after graduation.

On the other hand, Bangladesh's most important competitor, Vietnam, has now struck a free trade deal with the EU. This will result in a phased elimination of most EU tariffs on Vietnam's exports.

As things stand, there could be a striking coincidence in which Bangladesh's garment exporters would see tariffs on their exports to the EU rise from zero to about 10 per cent on an average in 2027 when the Vietnamese exporters would start enjoying duty-free market access.

The estimated impact of this situation – derived from a quantitative modelling exercise – seems to suggest a loss of up to one-third of Bangladesh's garment exports to the EU.

Even without considering Vietnam's trade deal with the EU, estimates arising from numerous sources indicate a potential export loss in the range $2-$6 billion because of the LDC graduation.

In the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, global discussions are currently underway about the United Nations-led LDC graduation process.

Bangladesh in collaboration with other LDCs could request the UN to defer its next triennial LDC status review (in 2021) until 2024 when the full impact of the unfolding crisis would be clear.

Given the unprecedented nature of it, the UN can also be asked to postpone all LDC graduation until 2030.

Any additional time obtained before graduation can help Bangladesh enormously in rebuilding its export sector.

China's move to give duty-free market access in 97 per cent tariff lines should be regarded as an extremely timely opportunity in this respect.

Despite slowing down considerably, the world's second largest economy is projected to expand 5 per cent per annum over the medium-to-long term, generating huge market prospects.

This is the first time China has given such an extensive and non-reciprocal market access to a country (Bangladesh) with potentially large supply-side capacity.

Unlike in developed countries, average tariffs in China, and thus tariff margins due to duty-free access, are much higher -- in the range 15-30 per cent for many products.

Such deep and comprehensive preferential market access can attract Chinese firms into Bangladesh to produce goods and export to China where wages have been rising reducing profitability.

Most global multinational firms are eager to capture market share in China, which is expected to expand from currently $14.5 trillion to about $27 trillion by 2030.

The new duty-free Chinese market access can greatly boost Bangladesh's attractiveness and competitive strength in attracting investments from those firms across the world.

Securing an extension of LDC graduation will provide investors a clear signal of their being able to make use of the duty-free market access in China for a longer duration thereby making their business propositions in Bangladesh much more viable and profitable.

For any populous and fast-growing developing country, local firms can find the expanding domestic market more attractive than foreign markets and they tend to invest less in export-oriented sectors.

The existing high tariffs then make the domestic market even more lucrative.

Furthermore, lack of strict enforcement of product quality and standards in the local market means firms targeting the domestic consumers tend to compromise with quality and, in turn, find it difficult to break into overseas markets.

Sustained appreciation of the real exchange rate has also acted as a disincentive for exporting firms.

Despite towering waves of uncertainty, there are tremendous opportunities for Bangladesh to be strategic and unleash its right policy options to come out of this crisis stronger than ever.

The writer is a director at the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh and chairman of the board of Research and Policy Integration for Development.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments