Telegrams that infuriated Nixon and Kissinger

REVIEWED BY SHAHNOOR WAHID

Blood Telegram is especially recommended for readers who were adults in those tumultuous days of 1971 and had suffered mental and physical torment while fleeing from the barbaric Pakistani killers. Each chapter of the book will bring back memories and readers will be able to relate them to their personal experiences.

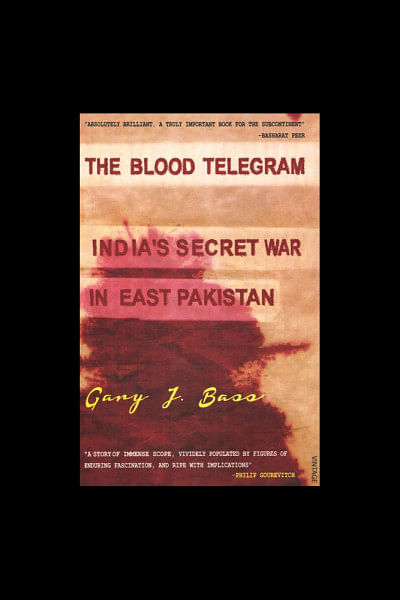

Reading through the pages of 'The Blood Telegram' was like watching the flashback of the events of 1971 in my mind's eye. It was like reliving the fearful days when the line separating life and death had thinned down perilously for the freedom-seeking Bengali people of the then East Pakistan. The book chronicles the political developments in Dhaka, Rawalpindi, Delhi and Washington during the painfully long nine months, at the decisive moments of the history of making of a nation state - Bangladesh. Blood Telegram provides authentic accounts of classified telegrams, responses, high level meetings, conversations, notes, comments, tussle between White House and the State Department, role of Henry Kissinger and imperceptive diplomacy of president Nixon and much more, all on the basis of recently declassified documents by the State Department, White House tapes and praiseworthy investigative reporting by some very courageous correspondents of the time.

One would be emotionally moved reading about the stand taken in favour of the Bengalis by Mr. Archer Blood the then American Consul General in Dhaka Consulate, and his staff members. He remained steadfast in his position against overwhelming odds and sent telegrams after telegrams to Washington regarding the genocide being perpetrated in East Pakistan by the West Pakistani military. He had taken great risks on his career while doing this despite words of caution from the US Ambassador to Pakistan Mr. Joseph Farland posted in Islamabad. If not with Nixon and Henry Kissinger, his telegrams had indeed worked at various levels of the then US administration and political circles to help perceive the truth about Bangladesh despite Pakistani propaganda. In the White House, Kissinger's Aides were shocked by Blood's reporting. "It was a brutal crackdown," said Winston Lord, Kissinger's special assistant...and Samuel Hoskinson, Kissinger's junior staffer for South Asia said, "He was telling power in Washington what power in Washington didn't want to hear."

About the US Consul General in Dhaka Gary Bass writes in the preface: "Archer Blood was a gentlemanly diplomat raised in Virginia, a WWII navy veteran in the upswing of a promising Foreign Service career after several tours overseas. He was earnest and precise, known to some of his more unruly subordinates at the US Consulate as a good, conventional man." Appalled by the brutality and wanton killing of the unarmed Bengalis on March 25, 1971 and the following days , Blood and his colleagues at the Consulate decided to relay as much of this as possible to keep Washington updated. He wanted the US Government to put pressure on the Pakistani government to stop the killings and send back the military to the barracks and go for political settlement. They continued to give details of the horrific slaughtering of the civilians in towns and villages. They wrote in details about the killings at the Dhaka University, of students, teachers and general staffs. One of Blood's cables used the term "Selective Genocide" and yet there was no response from Nixon. In Blood's words, his cables were met with "deafening silence." Why Nixon chose to ignore Blood's telegrams and similar texts from the US Ambassador to India Kenneth Keating?

Gary Bass writes: "Nixon enjoyed his friendship with Pakistan's military dictator, General Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan, known as Yahya, who was helping to set up the top secret opening to China. The White House did not want to be seen as doing anything that might hint at the breakup of Pakistan - no matter what was happening to civilians in the east wing of Pakistan."

When his volleys of cables failed to achieve desired results, it was on April 6 that Archer Blood dispatched his most damaging telegram from Dhaka. It formally declared their "strong dissent" - a total repudiation of the policy that they were there to carry out. Bass writes: "That cable - perhaps the most radical rejection of US policy ever sent by its diplomats - blasted the United States for silence in the face of atrocities, for not denouncing the quashing of democracy, for showing 'moral bankruptcy' in the face of what they bluntly call genocide." The full text of that dissent cable is given below.

Sub: Dissent from US policy toward East Pakistan

"With the conviction that US policy related to recent developments in East Pakistan serves neither our moral interests broadly defined nor our national interests narrowly defined, numerous officers of American Consulate General Dacca...consider it their duty to register strong dissent with fundamental aspects of this policy. Our government has failed to denounce the suppression of democracy. Our government has failed to denounce atrocities. Our government has failed to take forceful measures to protect its citizens while at the same time bending over backwards to placate the West Pak dominated government and to lessen likely and deservedly negative international public relations impact against them. Our government has evidenced what many will consider moral bankruptcy, ironically at a time when the USSR sent president Yahya a message defending democracy, condemning arrest of leader of democratically elected majority party (incidentally pro-West) and calling for end to repressive measures and bloodshed...We have chosen not to intervene, even morally, on the grounds that the Awami conflict, in which unfortunately the overworked term genocide is applicable, is purely an internal matter of a sovereign state. Private Americans have expressed disgust. We, as professional public servants express our dissent with current policy and fervently hope that our true and lasting interests here can be defined and our policies redirected in order to salvage our nation's position as a moral leader of the free world."

The message was signed by 20 officials from the consulate's diplomatic staff as well as the US government's development and information programs. Blood took full responsibility of authorising the transmission of the cable. He was aware that by sending the dissent cable he could wreck his career as a diplomat. A Consulate officer named Griffel said years later, "Blood risked everything."

About the reaction to Blood's dissent cable, Gary Bass writes: "The telegram detonated in all directions, to diplomats in Washington, Islamabad, Karachi and Lahore...it provoked rage at the highest levels in Washington. 'Henry was just furious about it," says Samuel Hoskinson. " Within hours nine of the State Department's veteran specialists on South Asia wrote to the secretary of state that they associated themselves with the dissent cable and urged a shift in US policy.

Although Blood and his team in Dacca were unaware of their newfound support, from Dacca to Delhi to Washington, the middle ranks of the State Department were massed in protest.

Blood's telegrams also reached Edward Kennedy whom Nixon loathed with all his heart. Kennedy used them in his speeches denouncing Yahya's killings, Nixon's silence and the use of US arms by Pakistan in the east wing. On May 3 he told the Senate that thousands or even millions of lives were at stake, "whose destruction will burden the conscience of all mankind." He complained that Blood's reports were being suppressed. Bass writes: "Other Senators rallied too, including some Republicans, and almost all Democrats. Senator Walter Mondale introduced legislation to suspend military aid to Pakistan. Senator William Fulbright, who chaired the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, asked the administration for the Blood telegrams and other Dacca cables. When the State Department refused, Fulbright and other Senators publicly excoriated the Nixon administration for downplaying the atrocities."

Meanwhile Archer Blood was called back from Dhaka and was given an unimportant desk at the State Department to his great dismay. Senator Fulbright summoned Blood to testify before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on June 24. Bass writes: "Blood, defying Nixon's policy, said that the United States should speak out against the killings, suspend economic aid to Pakistan, and pressure Yahya to make a political settlement." Four days later, Blood had to appear before Kennedy's own sub-committee. He was happy that someone of Kennedy's stature was taking interest in the Bengalis.

The book, Blood Telegram, goes on to open one widow after another on the eventful months of 1971, telling us about the Americans who stood up boldly to protest the killings of the Bengalis by the Pakistanis. He also talks about the bitter sweet dramas surrounding the birth of Bangladesh that unfolded in the international arena. While geo-politics took the centre stage, we waited and waited for the longest days and longest nights in the lives of every Bengali to come to an end. We waited for the sun to rise on a new country - Bangladesh - and it did without fail on 16 December, 1971.

Bangladesh recognises the contributions of Archer Blood and remembers him with profound respect and gratitude.

The reviewer works at The Daily Star. He can be

reached at: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments