After Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Paths taken by three protagonists of the Manhattan Project

The 6th and 9th of this month marked the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, that killed an estimated 120,000 people instantly. Radiation exposure would kill tens of thousands more. Much of the work toward building the bombs was done by the elite scientists and engineers at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico.

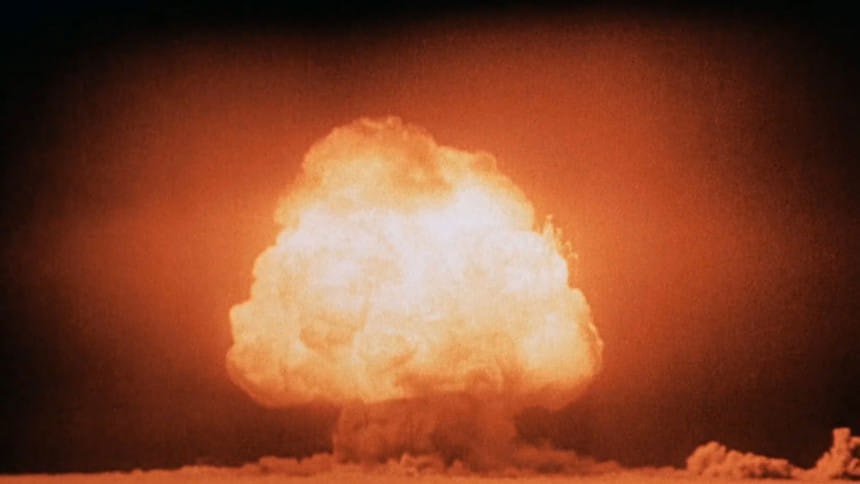

After three years of intensive research, calculations and brainstorming by them, the test bomb of the Manhattan Project–code name of the bomb-making effort–was detonated just before sunrise at the Trinity Site located in a parched landscape near Alamogordo, 400 kilometres south of Los Alamos. It created an enormous mushroom cloud some twelve kilometers high and ushered in the Atomic Age. Since then, our life became inextricably linked forever to the awesome power stored in the nucleus of an atom.

"Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds." These words from the Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita were chanted by a despondent Robert Oppenheimer, scientific director of the Manhattan Project, after witnessing the mind-boggling destructive power of his creation. The energy released by the bomb was compared by him "to the radiance of a thousand Suns." The fireworks from the explosion stood out in the minds of everyone within hundreds of miles of the site that morning. According to residents in faraway neighbourhoods, the Sun rose twice on that day.

The Trinity test was only a hint of the raw power of the bomb that was to come. Less than a month later, as the news of death and destruction at Hiroshima and Nagasaki reached Los Alamos, earlier exuberance of the scientists and engineers turned introspective. Some even questioned the morality of dropping the bombs without warning "against an enemy which was essentially defeated." Three months later, with an overwhelming feeling of guilt, Oppenheimer told President Harry Truman, "Mr. President, I have blood on my hands."

Oppenheimer had roped in some of the best minds of the scientific community including two internationally renowned émigré physicists–Hans Bethe and Edward Teller–to work on the Manhattan Project. Interestingly, because of his left-leaning political beliefs, Albert Einstein, who wrote a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt in 1939 urging that the United States should start its own nuclear programme to beat the Nazis in the race to build the bomb, was denied the security clearance needed to work on the project.

Soon after the war, Oppenheimer left Los Alamos and became director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. He also became a peace activist and vehemently opposed further proliferation of nuclear weapons on the grounds that they are more destructive than mankind could responsibly control and, thus, is a threat to civilisation. Furthermore, as an advisor to the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), he became an "apostle" for nuclear arms disarmament.

Oppenheimer reviled at the thought that history will remember him as one who gave mankind the means for its own destruction. At the farewell ceremony held in his honour at Los Alamos, he said, "If atomic bombs are to be added as new weapons to the arsenals of a warring world, or to the arsenals of nations preparing for war, then the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and of Hiroshima."

Because of his anti-nuclear stand, Oppenheimer made a number of personal enemies, among them Edward Teller, who was instrumental in scuttling his career. Their relationship had been rocky for a long time, but it came to a head in 1954. Miffed at his opposition to the development of the even more powerful hydrogen bomb, Teller convinced the AEC to try Oppenheimer before a tribunal of the commission for his past involvement with communist organisations and the possibility that he was a Soviet spy.

At the hearing, Teller delivered the knockout blow by asserting, "I would like to see the vital interests of this country in hands which I understand better, and therefore trust more." The trial ended with the revocation of Oppenheimer's security clearance, leaving his reputation in tatters. He was vindicated, albeit posthumously, after the transcript of the hearings, declassified in 2014, confirmed that he was never a security risk.

Teller may have won then, but it was a Pyrrhic victory. He was immediately declared a persona non grata at Los Alamos and became a pariah among the scientists who respected Oppenheimer.

In the last years of his life, Oppenheimer wrote about the problems of intellectual ethics and morality, particularly the dilemma he had faced when the interests of the nation and his own conscience collided during the war. Until his death from throat cancer in 1967, he lectured around the world, and was awarded the Enrico Fermi Award in 1963.

Hans Bethe returned to Cornell to resume his teaching career. However, the appalling images of death caused by the atomic bombs made him realise that he carried a heavier share of responsibility than most of his colleagues for contributing to the development of the fearful weapon of mass destruction. To extirpate his feeling of guilt, he made a deal with his conscience to work for a happy outcome of the "nuclear gamble" and to show to mankind the practical benefits of nuclear energy. Indeed, after the war, he vigorously pushed for peaceful use of nuclear energy. In his later life, he opposed President Ronald Reagan's space-based Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) missile system. His post-war work on the discovery of nuclear fusion, which fuels the Sun and the stars, earned him the Nobel Prize in 1967.

The remorseless Edward Teller instead became personification of Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove. He made a deal not with his conscience but, as his critics would say, with Mephistopheles, and invested his entire post-war professional life working to keep the United States ahead of the Soviet Union in the nuclear arms race.

Teller was fiercely anti-Communist and strongly believed that scientists at Los Alamos were too ambivalent about developing the next generation of nuclear weapons. Hence, he embarked on a forceful campaign to convince President Truman that an independent facility was needed for developing thermonuclear weapons. Consequently, in 1952, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory was established in California's Bay Area, which was used by Teller to develop the first hydrogen bomb. In the 1980s, he was a staunch advocate of SDI, aka Star Wars programme, at times overselling the feasibility of the programme.

And what about the scientists whose moral qualms deepened after the bombs were dropped? They left the weapons lab for the sanctuary of university labs and classrooms.

Seventy-five years after the carnage at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we still shudder at the images of extraordinary destruction and grotesque form of collective dying of innocent civilians. Peace-loving people all over the world marked the anniversary by expressing their amorphous fear of a full-scale nuclear war. They highlighted the threat of a world that continues to produce nuclear weapons, and appealed to everyone to wage a nuclear "moral revolution."

Quamrul Haider is a professor of physics at Fordham University, New York.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments