How they could have been

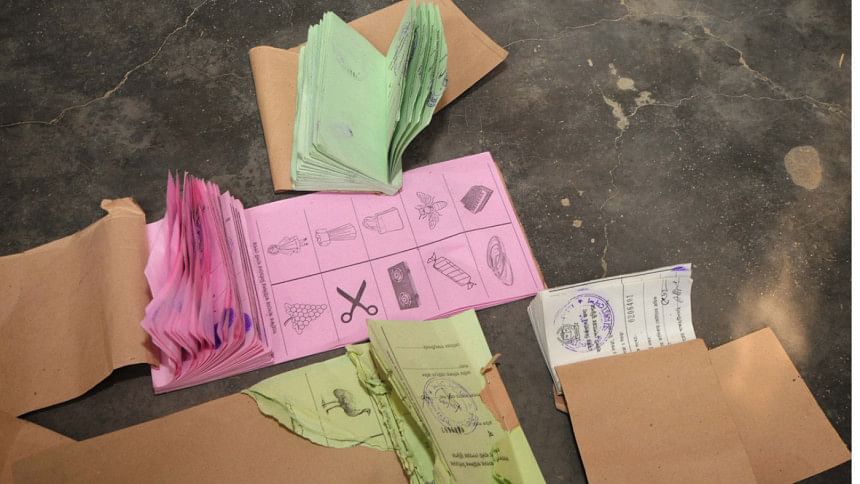

The municipal elections held on December 30 in 234 municipalities are considered neither 'credible' nor 'unacceptable' by any observer organisation. The Election Working Group (EWG), in its preliminary statement, said: "despite a significant number of electoral incidences of varying severity recorded on Election Day, most voters were able to employ their franchise and vote according to their will." Brotee, on the other hand, in its statement stated elections "apparently free and fair, barring some irregularities in all polling centres."

It is no surprise that the AL, who won the municipal election commented it to be "peaceful, free, fair and neutral" while BNP termed the election 'farcical and stage-managed".

The EC launched the municipal election journey with a few good initiatives. After passing the law, within a very short time, the EC announced the election schedule along with all preparations. It promulgated a good set of code of conduct to ensure a level playing field for all parties and candidates with a provision that very important persons (VIPs) and public servants, who enjoy government benefits, are not allowed to participate in electioneering or any of the election activities. It is admirable that EC stuck to its decision although AL made a request to reconsider this provision. It was also praiseworthy that the EC declined the request of Prime Minister and the President of AL to assign her party's Boat symbol to an independent candidate in a municipality as election law does not support it.

During the late campaign period, the EC took few strong decisions. On December 27, the EC directed the ROs (returning officers) to suspend voting if any polling stations were 'taken over'. On the same day, it also asked two AL lawmakers to leave electoral areas for violating the code of conduct as well as asked the authorities for the withdrawal of officers-in-charge of three police stations and changed an RO for their suspected bias towards certain candidates.

Against such good initiatives, however, we observed a significant number of violations of code of conduct and incidents of violence among the candidates and their supporters since the announcement of the election schedule which continued throughout the electoral cycle.

Firstly, during the submission of nomination papers and campaign period, we observed a significant number of violations of code of conduct by a few ministers and MPs, the candidates and their supporters. Although in a few cases, the EC directed the ROs to investigate the allegations, most of them were "found to be false". In a few instances, although the EC took legal actions, these were limited to issuing show-cause notice or fining a small amount of money although the code of conduct has the provision of rigorous imprisonment and cancellation of candidacy for such violations. As most of the ROs were recruited from civil bureaucracy and they worked closely with the ministers and MPs at the rural level, it was very tough for them to take any legal actions, even tell the truth through investigation. This not only hampered the electoral integrity throughout the electoral cycle but also impeded establishing EC's complete authority over the election administration.

Secondly, there is no scope to raise any questions against unopposed elections, but if an unopposed election is 'managed' by the candidates elected unopposed as well as other influentials, it must be investigated. Newspaper reports confirmed that candidates were threatened 'not to submit nominations' and forced to 'withdraw nominations' or became 'ineffective due to pressure' in a few municipalities. Although immediate and neutral investigation on those allegations was decisive for credible elections, the EC did not do so, even did not consider any of these allegations into account at all. This also obliterated the integrity of the elections.

Thirdly, similar to violation of electoral code of conduct, the EC failed to control violence throughout the electoral cycle. There were quite a few incidents of violence during the campaign, on election day, even in the post-election period including killing, attacks on vehicles and campaign prorammes, torching of vehicles and houses, creating panic among the voters and so on. The EC was found largely indifferent in taking necessary legal action which was essential for credible elections. The EC, until December 22, did not even discuss this issue in the Commission meeting which instigated election violence. Moreover, the law enforcing agencies, especially the police, did not provide full support by taking neutral actions against the actors of the violence.

Fourthly, the electoral process lacked of stakeholder consultations; but "building the public's trust in the election process is of utmost importance to election management bodies around the world" as consultation with stakeholders help increase transparency and build trust. The legal framework was amended without any consultation by the Parliament; the code of conduct was finalised without any consultation with the political parties although it was a partisan election for the post of mayoral candidates.

The analysis discussed above proves that the EC failed to establish its full authority over the election administration that was a must for free, fair and credible elections and there are two main reasons behind this.

The recruitment of ROs from the civil bureaucracy first of all, is not acceptable any more especially for local government elections. In the early period, officials from the civil bureaucracy were recruited as returning and assistant returning officers to conduct elections due to lack of staff of the EC Secretariat. But the situation has changed and after promulgation of the Election Commission Secretariat Act 2009, EC the Secretariat has become independent from the executive branch. Our civil administration is politicised – in most cases the appointment at the local administration is made on political consideration. Ultimately, they are the people of the government and after elections they have to go back to the government. In such a position, it is impossible for the civil servants to work with neutrality. In India, although returning officers are recruited from the government or from the local authority, ECI recruits observers of its own to watch the conduct of elections. These observers have the power to direct the returning officer of a constituency to stop the counting of votes at any time before the declaration of election results. He takes such a decision when he believes that there are irregularities in the electoral process which might influence the election results.

Secondly, law enforcing agencies must be brought under EC's jurisdiction. In many countries of the world, the security forces work under the direct supervision of the election management body (EMB). Costa Rica is one such example where the EMB establishes direct control of the Civil Guard (part of the domestic security forces) and elections are fully guaranteed to be free and without interference from the political authorities. Considering the context of Bangladesh, the legal framework could be revised with a provision that members of the law enforcing agencies must deploy from other parts of the country under the direct control of the EC and after election they will be sent back to their work place.

Integrity in elections depends on ethical conduct by electoral administrators, election officers, candidates, parties and all participants in the electoral process. It implies that all participants should behave in a way that promotes a free and fair process, and that discourages conduct jeopardising the integrity of the process. To achieve this, all participants must carry out their duties or roles in a professional, transparent and impartial manner.

The writer is the Director, Election Working Group.

E-mail: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments