Can Covid-19 become a catalyst for nutritional self-reliance?

Ever since the threat of Covid-19 first hit us, there has been a spike in online sales of both food and non-food items. For food in particular, it is difficult not to succumb to the alluring pictures of goodies posted on social media. In fact, for many of us, food consumption has actually increased, given the exposure to a wide choice, ranging from everyday foods to high-value ones, coupled with the ease of doorstep delivery. Covid-19 or not, many of us are largely unaffected in terms of having nutrient-rich diverse food on our plates. But let us ponder a bit on where all these foods originate from: the farmers.

Going by the regular media reports on hardships faced by farmers, particularly those producing highly perishable items, we know that they are having a hard time during this pandemic. It is heart-breaking to see gallons and gallons of milk being dumped, or the dejected look on the faces of vegetable producers, because of the rock-bottom prices, or the trail of forlorn cattle farmers waiting expectantly for a buyer. These are the people who toil to get food on our plates and yet they are the ones who have little on theirs.

While I come back to our farmers in a bit, let me dwell on the modern-day integrated food system that ensures the movement of food across the globe, the fruits of which we enjoy in our daily life. However, the robustness and sustainability of a system gets proven in times of adversity. Can we afford to unconditionally depend on the global food system to supply us with adequate food as and when we need it? Border closures, restrictions on travel and imports, and the necessity of quarantines in the current situation have exposed us to the uncertainties of disruptions in the supply chain. Even before the pandemic, we were being bombarded with the news of spiralling prices of onion, the near-essential item in Bangladeshi cuisine, following a crisis in the market.

Our hard-earned rice self-sufficiency is undoubtedly a remarkable feat for a nation that began its journey with literally nothing except its teeming millions. Our focus should now be on moving forward from here towards becoming nutritionally self-sufficient. The limited purchasing power of the masses has placed Bangladesh amongst those countries with the lowest per capita consumption of milk, meat, eggs, fruits and vegetables, not only globally but also within the South Asian region. Although recent trends of falling per capita rice consumption are encouraging since that implies a diversification of diets, we cannot become complacent and allow things to take their own course. Rather, we have to build on this development and aggressively focus on diversifying and intensifying our food production and consumption. Only then can we call ourselves "food secure" in the true sense of the term. This is where our farmers come in.

It is hard to find a farmer in Bangladesh who does not grow paddy and, that too, for most of the year. It is the lifeline of the farming community (and also for the rest of the population!). Based on the latest figures (2018) from Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, our rice production exceeds our domestic rice demand by more than 14 million tons. This is a stupendous quantity of excess rice, given that there are stocks in our silos too. Moreover, we do not export any significant quantity of rice. A quick calculation will reveal that this huge quantity of excess rice takes up more than 4.5 million hectares of agricultural land! This is not the optimal use of land resources in a country that is severely land-crunched. If this land could be devoted to other agricultural production activities, it would be a boon for our food sector.

A lot of work has gone into making Bangladesh the bountiful granary that it is today and understandably so, given the haunting memories of famine and starvation and the constraints faced by the government to import food, soon after independence. The combination of political determination, advances in research and the toil of the farmers have made it a reality. But the rice-centric efforts have relegated other high-value, nutrient-dense food crops to the background. While rice will, for obvious reasons, continue to be the prime agricultural produce of the country, the focus needs to shift to increasing cereal productivity rather than coming up with newer varieties of rice. We already have more than 100 rice varieties at present. So there is an urgent need to review the current mandate of the agricultural research organisations to meet emerging needs with a focus on diversification out of primary staples. For instance, research aimed at introducing stress-tolerant, high-yielding varieties of pulses (often called the "poor man's protein") can substantially contribute to reducing Bangladesh's dependence on imported pulses.

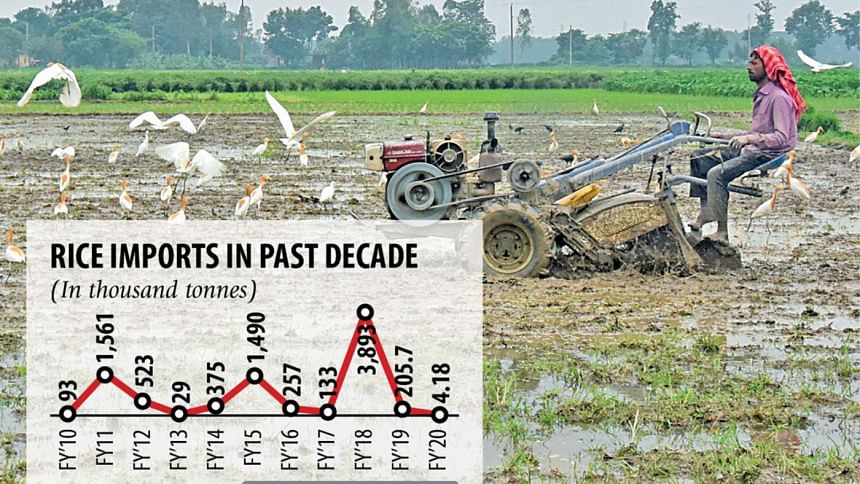

Given that rice is a traditionally grown crop as well as one with a high shelf-life, growing rice has become the farmers' comfort zone. The risk-averse farmers are reluctant to try out new crops. If they are to be convinced to diversify their output, they have to, first and foremost, have the assurance that they will get a proper price for their produce. No rational being will expend their time, energy and resources on something that brings them no return at all. But instances of cheap imports flooding the market have seriously hampered the livelihoods of thousands of Bangladeshi farmers. Not even being able to recover their production costs, many farmers have simply dumped their produce. The policy makers' import decisions have cost them dearly. To cite a couple of examples, import of cheap rice at zero tariff, following the flash floods of 2017, caused a glut in the market, which got exacerbated when farmers re-bounced with a bumper harvest in the next season. Meat imports have continued despite Bangladesh becoming self-sufficient in meat production. Bulk imports of powdered milk is adversely affecting the local dairy industry.

We do not know when the pandemic situation will cease and things will return to normalcy, but we must be prepared for any exigencies in the future. Compared to many countries, Bangladesh has done relatively well in the current Covid-19 situation but there is no guarantee that we will be able to pull through just as well, should another contingency strike us. For a net food-importing country such as ours, the possibility of such contingencies is always accompanied by a perennial fear of negative shocks to food imports. The first thing that we have to secure, beyond protecting the people from the direct effects of the contingency, is to ensure adequate amounts of healthy food on our plates. But how?

The answer is obvious. If we want to safeguard ourselves, we will clearly have to create our own resilient domestic food system. It may appear absurd to be speaking of inward-looking strategies in this day and age but our experiences point towards the need for a renewed focus on food self-sufficiency through the lens of nutritional self-sufficiency. Covid-19 should be taken as a clarion call to build our own capacity to cater to the dietary requirements of our people, independent of what the external conditions are. Indeed, this is not to say that we stop all food imports, because ending trade is not a desirable or likely outcome for policy. What we need to aim for is nutritional self-reliance as well as striking a balance between the rural producers and the urban consumers through appropriate trade policies.

A holistic approach is key, starting from detailed planning to effective and sustained execution. Such an approach should encompass the entire gamut of production activities. These include national estimates of nutritional requirement, area mapping to cater to these estimates based on the agro-ecological suitability of each area, and comprehensive farmer support to incentivise the required production. Such support should also include reliable agriculture extension services. Off-field, there must be a robust market monitoring and information system which would be reflected in the prices. Ensuring safe produce should also be a part of this system that will generate consumer confidence in locally produced products. This is very important since the consumer confidence—particularly with regard to highly perishable commodities like milk—is rather low and is driving many to opt for foreign brands. There is a dire need to deal with the agriculture sector in a sensitive way, minimising the often unscrupulous activities of middlemen and other actors. Finally, adequate investments, including on storage and transportation infrastructure, must be made to strengthen the supply chain that will link the farmers to the food that ultimately reaches our homes. An integral part of this strategy must also be a contingency plan in the face of natural calamities that may adversely affect agricultural production.

This, undoubtedly, is a lot of work and requires determination and dedication to pull through. But this is also something that we must do, given the far-reaching effect of the food sector on the rest of the economy. Once we are able to set up a self-sustaining system, we can focus our energies on other aspects instead of struggling to ensure food for all. Who knew that Covid-19 would come and create such havoc? One thing that is certain is change—big or small. And the current pandemic is one such big change. We must be prepared for such unforeseen changes.

Firdousi Naher is a professor at the Department of Economics, University of Dhaka.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments