Why do we have to take to the streets for justice?

Eleven people have so far been arrested in connection with the Noakhali gang rape. Most of the suspects were arrested within days after the video of the heinous crime landed on social media. The graphic content rattled the nation as people of different quarters took to the streets across the country demanding justice. What would have happened had the video not gone online? After all, it happened more than a month ago and nobody knew anything. Now that we know she had been through this ordeal for many months at the hands of an organised gang led by a Delwar Hossain, we can genuinely raise the question, did the law enforcing agencies not know about Delwar and his unscrupulous gang?

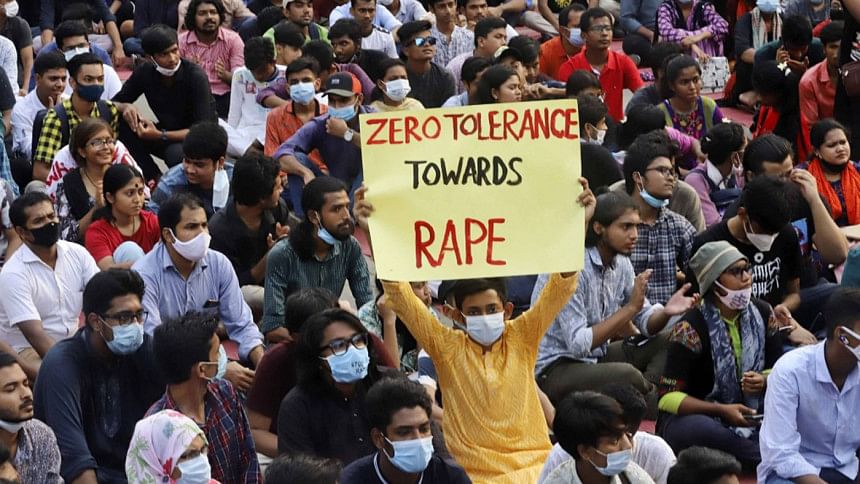

This is not the first time that the people, and the youth in particular, have taken to the streets to demand justice. Whether we support them or not, there is a perception that justice is not always a straightforward process, even in a democracy that is built upon the principles of rule of law and protection of human rights of all the citizens.

The extrajudicial killing of Sinha Md Rashed Khan and subsequent incidents are blatant examples of abuse of power by state institutions and the people within them. Immediately after the killing, the local police made every effort to make it look like a usual case of drug peddling. Members of the local police frantically tried to kill the truth in a bid to conceal years of corrupt practices in the name of maintaining law and order. To divert peoples' attention, the police resorted to character assassination of Shipra Debnath. Similar to Noakhali, people from all walks of society condemned the killing and demanded an impartial and transparent investigation into the incident. The media too reported on the corrupt practices of members of the local police. It will not be unjust to say that peoples' agitation and media reporting contributed to unearthing many facts that otherwise would never be known.

The rise of Delwar and his gang is not a lone example of political patronage. In the past, we have seen a similar uprising of criminals leading to a crime empire being built with political blessings and institutional patronage. Readers may recall that the most powerful students' movement after the 90s movement for democracy was against organised rape. Having lost faith in the political system and institutions, the students of Jahangirnagar university organised the anti-rape movement in 1998 against Jashim Uddin Manik and his gang. Over the years, the students witnessed how criminals rose to power under political blessings and how the institutions failed to check them. This led them to take to the streets to get justice.

In most cases, a criminal does not commit a crime on a mere whim. It is the result of abuse of power. Such a person gains and maintains power over an individual, group or community within a society and subjects them to various forms of abuse, including but not limited to sexual, physical, financial and psychological abuse. The curious cases of exercise of power and control by Jashim Uddin Manik, Tufan Sarker, Rifat Farazi, OC Pradeep, Saifur Rahman and last but not least, Delwar Hossain, indicates their motivation toward psychological projection, greed and personal gratification with systematic political and institutional blessings—some politicians facilitated their rise to power and institutions bestowed with the responsibility of protecting the victims turned a blind eye, until people started demanding justice.

Sadly, our political process is such that politicians always tend to shrug off their responsibilities and deny existing flaws. It immediately starts a blame game as if it is the cause and effect of the other party. The state institutions too, play a reactive role instead of a proactive one in protecting the human rights of the people. They act only after it turns into a sensational case. The National Human Rights Commission, for instance, have hardly conducted any investigations into extrajudicial killings, which constitute extreme abuse of power, although it enjoys the power of a civil court. Unfortunately, civil society organisations also do not always act beyond political ideology. Such inaction or reactive actions have created a vacuum that leads to people taking to the streets for justice.

Demanding justice on the streets is the last resort for people, but it is likely to happen every now and then when the institutions of society continue to fail. The question is, how did we get here? The answer is infuriating and disheartening—we have been here for quite some time. The culture of injustice against the vulnerable and powerless has been built and fortified over time. Over these years, we have failed to build a democratic and inclusive society. We have beautifully decorated our democratic institutions but without the desire and capacity of serving the vulnerable and marginalised people who comprise the major portion of the population.

Then what is the best way to fight and mitigate such violations of human rights and rule of law? We have to fight both the criminals and the background of the crime. It will be a mistake to judge the MC College and Noakhali gang rapes, and the brutal killing of Sinha, merely through the lens of criminal laws. When the country speaks in the same language by demanding quick justice for the victim, the culprits are more likely to be punished under the existing laws of the country. To prevent a repetition of such crimes, we need to simply understand the criminology—what led to Delwar's uprising and how did OC Pradeep, being an officer of law and order, continue his wrongdoings for years?

Many human lives were saved in the month of September as it did not see any extrajudicial killing. The countrywide agitations and media reporting against extrajudicial killings contributed to this achievement, which otherwise might not have been the case. But it is an underlying fact that when a society is politically and economically strong, the crime rate will decrease and we will not need to take to the streets for justice. The renewed stance of the government in the backdrop of the Noakhali gang rape is encouraging. Amending the Women and Children Repression Prevention Act, 2000 may not be enough. Different provisions in the Evidence Act and Code of Criminal Procedure and prosecution of violence against women need to be revisited as well, but nothing can be achieved without a strong political system.

A strong political system and its institutions will stand ready to fight for its people irrespective of age, gender and economic status. Therefore, it would be far more effective to invest in criminology to analyse the main reasons behind the crime and eliminate them. A society without crime is perhaps impossible. The criminology here, in this case, is that we have a fair and transparent political process in place and that the institutions are not blindfolded and biased.

Meer Ahsan Habib is a communication of development professional.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments