Facade of workers’ safety beginning to show cracks during the pandemic

More than seven years after the Rana Plaza disaster in 2013, issues related to fire, electrical and structural safety in hundreds of the nation's garment factories have improved from before. For example, according to the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety's website, 84 percent of factories under the Accord have corrected their outstanding structural issues. Covid-19, however, has put a spotlight on just how "safe" workers really are. While building structures have been made safer over the years, the larger structure of the global supply chain was intentionally left intact. Inherent inequities endemic in all layers of this complex network have left workers vulnerable, and their livelihoods have become even more precarious under this current global pandemic.

A new report released by The Subir and Malini Chowdhury Center for Bangladesh Studies at the University of California, Berkeley in collaboration with the James P Grant School of Public Health (JPGSPH) and the Centre for Entrepreneurship Development (CED) at BRAC University finds that, based on export earning data, the garment industry lost USD 4.6 billion between March and May this year. Bangladesh, like many other export oriented countries, is part of an unbalanced global system, characterised by contracts that tilt the terms of business in favour of global brands and legal loopholes that can be used to cancel orders, refuse payments and demand discounts. This unequal distribution of power is difficult for suppliers during the best of times, and even more devastating during these unprecedented times.

Seven years ago, many global retailers boldly declared that, "it would no longer be business as usual." While many joined efforts to monitor factories for structural violations, most have also continued to pursue a sourcing strategy that forces suppliers to continuously produce products faster and cheaper. Many studies show that this business model, characterised by hyper-flexibility and limited transparency, contributes to increased incidents of sexual harassment and gender-based violence and to overall declines in the mental and physical health of workers. When we say workers are now safer, we really have to question what we mean by "safety." In my mind, these factors certainly do not contribute to any sense of security, especially for female workers.

After much confusion early on in the pandemic between the government and factories about whether workers should return to work or not, this report finds that more than 87 percent of workers said their factories have introduced new precautions to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. Despite the various measures in place, however, whether workers feel "safe" is questionable, since almost 60 percent of workers fear that they are somewhat likely or very likely to get infected by the virus in their factory. The practicality of instituting measures to limit the transmission of a contagious virus is difficult, and probably even impossible, in high-density factory settings. More than half of workers would not be able to isolate at home if they contracted the virus, even though 66 percent said that their factory would send workers home if they show symptoms. If factories are going to continue their operations during this crisis, there needs to be certain contingency plans in place for workers who become sick, including providing places to isolate, health care provisions, financial support, and job security.

It is difficult for workers to be "protected from harm," when they are forced into practices that negatively impact their health. We know that salary levels for garment workers have never been adequate for them to support their families, meet their required calorific needs, and accumulate savings. According to the Institute of Nutrition and Food Science at the University of Dhaka, a worker must spend at least Tk 3,270 per month on a variety of foods to meet their calorific needs; they found, however, that workers really have the ability to spend only about Tk 1,110 a month. And this was during normal times. In our survey, we found that in April, when salaries hit their lowest point, female garment workers received only Tk 5,742 and male workers only Tk 7,739 for that month. Those in helper positions in factories (82 percent who are women) received only Tk 5,170 in April. Thus, it is not surprising then that 77 percent of workers in this report said that it was difficult to feed everyone in their household. Sixty-nine percent of workers ate less protein rich foods like meat, fish and eggs in May compared to February, while 40 percent ate more pulses, like lentils and chickpeas during this time. I think it is high time to revisit the idea of a living wage.

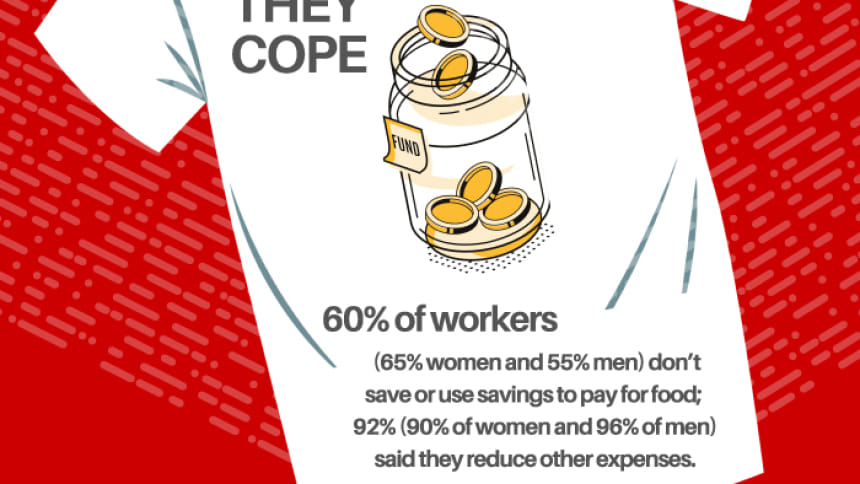

Protection from other "non-desirable outcomes" is impossible when workers are unable to save or are forced to reduce expenses in other areas, just to meet their very basic needs. A 2018 study by the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) found that 45 percent of garment workers are unable to save anything from their earnings. When asked how they have coped during this recent crisis, 60 percent of workers said they don't save or have used their savings to pay for food and an overwhelming 92 percent said they had to reduce other expenses. Not being able to save or cutting costs in other essential areas, like healthcare, puts workers at even greater risk of not being able to mitigate future economic or health crises.

An article in The Daily Star from September 9, 2020, finds that Bangladesh has the fewest social protection initiatives in the Asia Pacific region, according to a United Nations position report: "The organisation broke down "social protection" into eight categories... According to the report, Bangladesh is only providing income support, or social assistance. The report iterates the necessity of preventing job losses and providing social protection to those rendered unemployed." In our survey, 90 percent of workers said they did not receive any support from the government during this pandemic. The lack of universal social provisions for all, but particularly for those who work in an industry that has been the engine of economic growth for the country over the last four decades, is not only shocking, but highly irresponsible. According to the Clean Clothes Campaign, "The severity of this crisis could have been averted if living wages had been paid, and social protection mechanisms had been implemented."

By all definitions, garment workers are not safer now, especially under this current crisis, compared to seven years ago. This pandemic offers us an opportunity to think about the gross inequalities that are present at all layers of the global supply chain and re-examine the factors that prevent constructing work environments that are truly safe, in the fullest definition of the word.

Sanchita Banerjee Saxena, PhD is Director of the Subir and Malini Chowdhury Center for Bangladesh Studies and Executive Director of the Institute for South Asia Studies at the University of California, Berkeley.

Comments