Using AI, Canadian city predicts who might become homeless

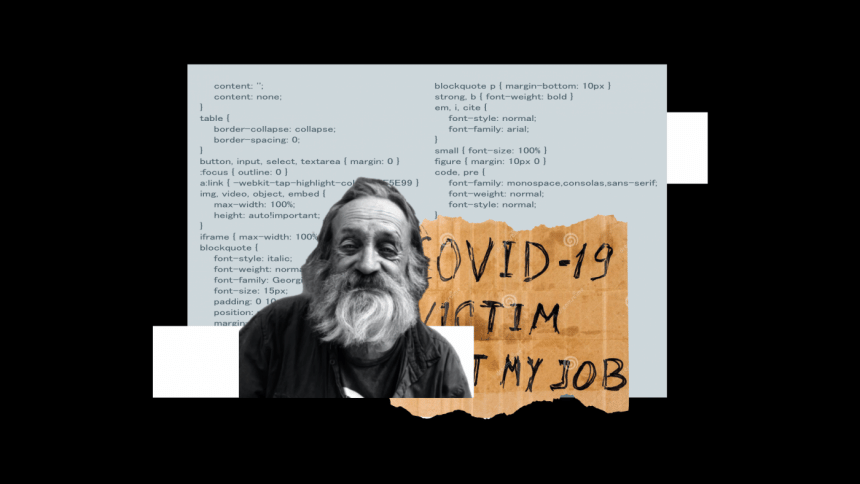

As makeshift tent cities spring up across Canada to house rough sleepers who fear using shelters due to covid-19, one city is leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) to predict which residents risk becoming homeless.

Computer programmers working for the city of London, Ontario, 170km southwest of the provincial capital Toronto, say the new system is the first of its kind anywhere and it could offer insights for other regions grappling with homelessness.

"Shelters are just packed to the brim across the country right now," said Jonathan Rivard, London's Homeless Prevention Manager, who works on the AI system.

"We need to do a better job of providing resources to individuals before they hit rock bottom, not once they do," he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Canada is seeing a second wave of coronavirus cases, with Ontario's government warning the province could experience "worst-case scenarios seen in northern Italy and New York City" if trends continue.

Homeless people are particularly at risk of being infected and infecting others during the pandemic, due to weakened immune systems and poor access to shelter and sanitation, health experts say.

Launched in August, the AI system analyzes the personal data of participants to calculate who faces having nowhere to sleep for an extended period, said Matt Ross, an information technology (IT) expert with the city who helped build the program.

As a test, the system, called the Chronic Homelessness Artificial Intelligence model (CHAI), tracked a group of individuals for six months before its formal launch in August.

Over that period, CHAI saw a 93% success rate in predicting when someone would become chronically homeless, Ross noted, adding it is now meeting or exceeding that rate.

By using the system to anticipate who is likely to become chronically homeless, the city can prioritize how it works with those individuals to try and get them into safe housing or get them access to health services they might need, Rivard said.

'MASS HOMELESSNESS'

Chronic homelessness refers to someone who has been staying in a shelter for 180 days or more in a year, Rivard explained.

Those individuals use 12 times more resources than people who are occasionally homeless, he said, so addressing their situation can save time and money in the long run.

City staff are currently working with local shelters, community groups and homeless people on how best to use the new AI data, Rivard added.

Annually, more than 230,000 people experience homelessness in Canada - "about 35,000 on any given night," said Tim Richter, president of the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness, an advocacy group.

Richter blames government cuts to affordable housing and other programs in the late 1980s and early 1990s for what he calls the "explosive growth" of "modern mass homelessness" over the past 30 years.

TRANSPARENT AI

When city officials first suggested using a computer program to predict chronic homelessness, it "raised some red flags" related to privacy, said Peter Rozeluk of Mission Services of London, a nonprofit that runs homeless shelters.

"I suppose whenever anyone uses the term 'AI', it can seem dystopian, simply because of how the media and Hollywood has depicted artificial intelligence," Rozeluk said.

After discussing the proposal with officials, he said he supports its general goal of getting better data to aid in decision making.

The AI program is only applied to consenting individuals, said developer Ross. Participants can quit the program at any time and their data will be removed from the model, he added.

His team of data scientists do not have access to the real names of the individuals involved.

Instead, each person is given an identifying number which is run through the system along with other data, including their age, race, gender, military status, the kinds of city services they have accessed, and how often they sleep in shelters.

Unlike most other AI systems, which produce their final conclusions without revealing the steps taken to get to them, London's technology can explain how and why it reached assessments about an individual's risk level, Ross said.

Building the system cost about C$14,000 ($10,660). All of that money came from the city's IT department, meaning CHAI is not taking resources away from frontline services for the homeless, such as shelters, he noted.

So far, the system has identified at least 88 people at risk of chronic homelessness, in a city of about 400,000 residents, said Rivard at city hall.

According to the model's predictions, a single male who has stayed in shelters, is older than 52 and has no local family is often at high risk of becoming chronically homeless, especially if he is a veteran or an indigenous person, Rivard said.

While the AI provides information about an individual's risk of becoming homeless long term, all decisions related to deploying services are kept in human hands, he stressed.

PRIVACY ISSUES Two unaffiliated computer science experts and a privacy lawyer told the Thomson Reuters Foundation that the program seems to take the necessary steps to protect users' personal information.

"It looks like they have put a lot of thought into doing it right," said University of Ottawa law professor Teresa Scassa, who studies AI and privacy.

The designers have ensured that the data put into the system is standardized and accurate and meets national guidelines on the ethical use of automated decision-making, she said.

Amulya Yadav, who teaches information sciences and technology at Pennsylvania State University and has studied AI and homelessness, said London's initiative is an example of how machine learning is "being democratized".

"The barriers to entry are being reduced," he said. "I really hope they pull it off well and it's the first of many." Still, Scassa, Yadav and other experts worry about what could happen to sensitive data on vulnerable residents going forward.

"It is paramount to think about not just what our data is used for, but (also) 'what can our data be used for in the future?' - and assume whoever holds the data has no scruples," said Paulo Garcia, assistant professor of computer engineering at Ottawa's Carleton University.

If a new government came into power looking to cut costs, for example, this information could potentially be used to determine who is taking up large amounts of resources and where funding could be slashed, Scassa said.

Rozeluk, who works on the frontlines of Canada's homelessness crisis, has a different concern.

Predicting when someone might become chronically homeless is less important than providing actual housing, he said.

Studies have been done for decades on the issue and the consensus is clear, Rozeluk said: "The solution to homelessness is safe, adequate, affordable housing ... and providing support afterwards." ($1 = 1.3133 Canadian dollars) (Reporting by Chris Arsenault, Editing by Jumana Farouky and Zoe Tabary. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments