Tipu Sultan: Rocketman

Imagine you're a young Scotsman. You took a job as a security guard for a multinational corporation operating in India, because it's 1799 and it beats being home looking at sheep for a living. Your employers, the East India Company, are mixed-up in a war against a local leader.

You don't much like this man "Tippoo of Mysore", a "Mussulman", enemy of Britain, and rumoured tyrant. Worst of all, he'd openly been in communication with Napoleon, who'd just conquered Egypt and planned to stage an invasion against Britain's Indian holdings from there, with Tippoo's help. Lucky for Britain by this time Nelson's fleet had sunk Napoleon's at the Nile, leaving him stuck without a ride. With his ally checkmated, it's time to remove the last imminent threat to British interests in India, and rub Tippoo out. The British forces are three armies strong, and the fourth war against Mysore should be a British victory.

And it will be, but you won't live to see it. Your first clue is the whooshing noise coming from above your head. You look up at the sky, just in time for your night vision to be shattered by a bright boom. Screams in many languages as dark shafts fly into the troops. Not arrows, but despite the explosions clearly not cannon. Rockets, but a far cry from the simple fireworks you know. The ones that do not explode are bounced and propelled along the ground, snaking their way along and slicing flesh with the blades attached to them. The bamboo shafts the rockets are attached to cut and maim and break apart as shrapnel. Dimly you realize that the heavy blades are causing the rockets to fly erratically in crazy spirals, scything through the air. One falls at your neck, ending this exercise of your imagination.

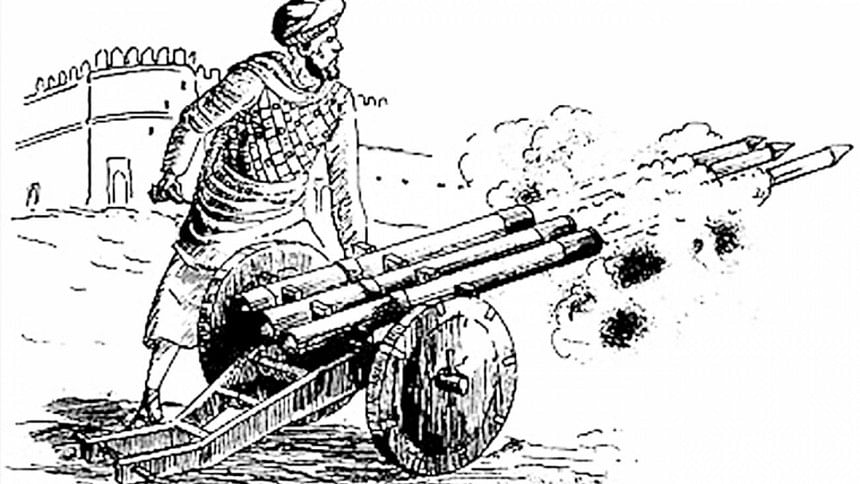

Since its invention in China rocketry had become ubiquitous from Japan all the way to England and across the ocean, but it was not until Tipu Sultan of Mysore and his father Hyder Ali arrived onto history that it became a serious weapon of war. The Mysore rocket was cased in soft iron tubes, unlike the paper casing familiar to the British. This made it possible to create greater internal pressure: more lift, more thrust. A Mysore rocket with a pound of powder could go as far as 1000 yards. The black powder propellant in the rockets could not be reliably counted on to explode on impact, so instead spear-tips and swords were affixed to the end. The entire object was a hell of a thing to have shot at you, and Tipu made it a point to organize 200-man rocketry detachments into each division of his army. The weapons could be carried by a single soldier, or wheeled onto the battlefield on devices capable of firing as much as ten at a time.

The Mysore rocket was a formidable weapon, but inadequate. Tipu's river island fortress of Seringapatam was stormed on the 4th of May, and Tipu himself discovered dead with a bullet to his head. In an ironic coda, the British acquired 600 rocket launchers, 700 active rockets, and 9000 empty ones. These examples and the experiences of Mysore campaign veterans provided the backbone for the development of the Congreve rocket at the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich in 1805. By the time they entered active service against Tipu Sultan's long-distance friend Napoleon, the Congreve rocket could hit a ship at 3000 yards with 32 pounds of powder.

I think we've all had friendships that bit us in the bum like that.

Zoheb Mashiur is a prematurely balding man with bad facial hair and so does his best to avoid people. Ruin his efforts by writing to [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments