Do the books on Trump qualify as exposé?

As of this writing, the United States is currently in the final weeks of its most partisan and controversial presidential election in 150 years, in which the Democratic candidate, former Vice President Joe Biden, has been forced to do most of his campaigning online or in carefully-masked and managed events, and his rival, Republican President Donald Trump, has resumed holding crowded indoor campaign rallies despite the warnings of his own government that such gatherings are potentially deadly super-spreader events.

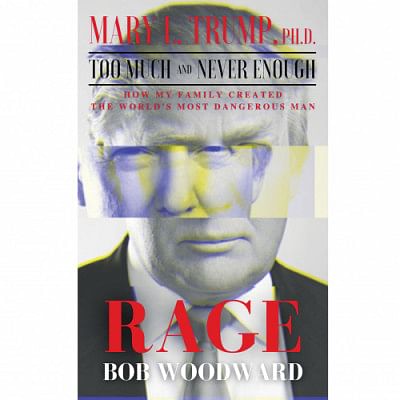

When a political contest is therefore clearly not so much a battle of ideologies as a clash of realities—Biden is campaigning in a US racked by plague and resulting economic depression, Trump is campaigning in a US that's largely put the virus behind it—there can be no neutral corners. This is reflected in the giant glut of books flooding the election season. Two of the best-selling and most-discussed of those books are Rage, an inside account of the Trump White House by two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Bob Woodward, and Too Much and Never Enough, an inside account of the Trump family by Donald Trump's niece Mary Trump (both are published by Simon & Schuster, which also published former National Security Advisor John Bolton's bestselling The Room Where It Happened).

Woodward's style will be familiar to readers of his previous Trump-centred bestseller, Fear: Trump in the White House (2018), but the actual contents of Rage will be familiar for an entirely more recent reason: Woodward and his publisher leaked audio portions of the interviews Trump gave to Woodward back in March, interviews in which Trump can be heard confessing that he knew exactly how deadly COVID-19 was and deliberately chose to lie about it to the American people.

Immediately after these clips began surfacing, news outlets put together damning compilations of the dismissive, trivialising things Trump was saying about Covid publicly while he was privately telling Woodward how dangerous it was. Some of those news outlets also ran segments questioning Woodward's decision to sit on those audio recordings throughout all those months when pandemic death-tolls were rising in America, only to release the excerpts when the timing would most help the sales of his book.

Likewise Too Much and Never Enough, Mary Trump's much-debated exposé of the Trump family's sordid psychological history, in which her grandfather Fred Trump mercilessly harassed and abused her father Fred Jr while at the same time ruthlessly creating the family atmosphere that would turn his younger son Donald into the kind of twisted sociopathic monster Mary Trump has subsequently been describing on every cable news show, political fundraiser, and podcast that will have her. Mary Trump, too, has occasionally been criticised for the timing of her book by people who naturally wonder why she didn't warn the American people about Donald Trump, say, back in 2015 when many of them were first making up their minds about whether or not to vote for him.

Both Woodward and Mary Trump have offered defenses against these charges of profiteering at the country's expense. Woodward has said he doubts his revelations would have made any difference back in March. Trump has said it was only when her uncle's administration started putting immigrant children into chain-link cages on the southern border that she was prompted to write a tell-all.

This kind of snivelling has been a hallmark of Trump's first term. At every turn, the responsible people, the "adults in the room," have seen Trump's narcissistic imbecility at close range, heard him talking about using nuclear weapons against hurricanes or admitting on national television that he's perfectly open to receiving foreign interference in US elections, and they said nothing publicly, did nothing publicly, and meekly waited to be fired by tweet. People like former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, former National Security Advisor HR McMaster, General James Mattis, and even Bolton, who announced that he would defy a Congressional subpoena in order to safeguard his book's payday—all of them held their tongue rather than sound an alarm when it might have done some good.

But as the carefully-timed leaks from Woodward's book and the barrage of pre-publication interviews by Mary Trump indicate, these authors never entirely hold their tongues. They leak. They tease. They flirt with their civic duty to inform the American people about weird, violent, or potentially criminal attitudes and behaviours held by their president, because the flirting helps their own paychecks. And all those leaks and teases add up over the years (or indeed over the decades, since New Yorkers were learning with shock and disgust back in the 1990s plenty of the same kinds of things the world has been learning since 2016) into an atmosphere of their own, a background radiation of corruption and venality that has slowly, subtly crept into the bedrock of the Donald Trump brand.

It reaches the point—it has long since reached the point—where that environment makes it categorically impossible for any of these new books to work as genuine exposés. When a new book breathlessly reveals further proof of Rex Tillerson's growled comment that Trump is a "[you-know-what] moron," we aren't surprised, because we all watched Trump publicly display an official weather service map of the path of Hurricane Dorian—a map Trump had altered with a Sharpie in order to make it reflect a mistake he'd made about the hurricane's path. When a new book offers new "behind-the-scenes" revelations about Trump's racism or sexism, the most common response is "We already knew that, didn't we?"—because Trump himself commented publicly that four US Congresswomen, all Americans and three born in the States, should "go back" to the crime-ridden countries from which they came.

For the first time in US history, tell-all books have become confirm-all books, and this has shifted the point of their existence squarely from the subject to the author. If what you're telling your audience isn't new to them, when you tell them becomes all the more important.

The law of the 2020 election holds for books like Bob Woodward's or Mary Trump's, regardless of the outcome at the polls: there are no innocent bystanders. Both of these authors stayed silent on what they knew until it could most benefit them financially, regardless of the harm it did to the country. They are not exposés of Donald Trump; in other words—they are Donald Trump.

Steve Donoghue is a book critic whose work has appeared in the Boston Globe, the Wall Street Journal, the Christian Science Monitor, the Washington Post, and the National.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments